Every successful interview starts with knowing what to expect. In this blog, we’ll take you through the top Wideband and Narrowband Signals Analysis interview questions, breaking them down with expert tips to help you deliver impactful answers. Step into your next interview fully prepared and ready to succeed.

Questions Asked in Wideband and Narrowband Signals Analysis Interview

Q 1. Explain the difference between wideband and narrowband signals.

The key difference between wideband and narrowband signals lies in their bandwidth – the range of frequencies they occupy. A wideband signal occupies a relatively large bandwidth, meaning it contains a broad spectrum of frequencies. Think of a wideband signal like a bustling orchestra, with many instruments playing different notes simultaneously. In contrast, a narrowband signal occupies a small bandwidth, focusing its energy around a single, central frequency. Imagine a narrowband signal as a solo flute playing a single, clear note. This difference significantly impacts how these signals are generated, transmitted, processed, and applied.

Q 2. What are the advantages and disadvantages of wideband and narrowband systems?

Wideband Systems:

- Advantages: High data rates, robustness to multipath fading (signal reflections), better resolution in radar and imaging applications.

- Disadvantages: Higher complexity and cost, increased susceptibility to interference, requires more spectrum.

Narrowband Systems:

- Advantages: Lower complexity and cost, less susceptible to interference, requires less spectrum.

- Disadvantages: Lower data rates, vulnerable to multipath fading, poor resolution in radar and imaging applications.

For instance, Wi-Fi uses wideband signals to achieve high data rates, while traditional AM radio broadcasts use narrowband signals to conserve spectrum.

Q 3. Describe different modulation techniques used in wideband and narrowband systems.

Wideband Modulation: Techniques like Orthogonal Frequency-Division Multiplexing (OFDM) are commonly used. OFDM divides the wideband signal into many narrowband subcarriers, each carrying data. This allows for efficient use of the bandwidth and robustness to multipath fading. Another example is Ultra-Wideband (UWB), employing short pulses spanning a very wide frequency range, achieving high data rates with low power consumption.

Narrowband Modulation: Amplitude Modulation (AM), Frequency Modulation (FM), and Phase Shift Keying (PSK) are common techniques. AM varies the amplitude of a carrier wave, FM varies the frequency, and PSK varies the phase. These are often used in legacy communication systems due to their relative simplicity.

Q 4. How do you handle noise in wideband and narrowband signal processing?

Noise handling differs significantly between wideband and narrowband systems. In narrowband systems, filtering is highly effective. We can design a narrowband filter that precisely targets the signal frequency, effectively rejecting much of the surrounding noise. Imagine using a sieve to isolate the desired grains from a mixture.

In wideband systems, the noise is spread across the entire bandwidth. Techniques like spread-spectrum modulation (as used in GPS) and matched filtering become crucial for noise reduction. Matched filtering optimizes the signal-to-noise ratio by correlating the received signal with a replica of the transmitted signal. This is analogous to listening for a specific, known melody amidst a cacophony of sounds.

Q 5. Explain the concept of signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and its importance.

The Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) is a crucial metric representing the ratio of the signal power to the noise power. A higher SNR indicates a stronger signal relative to noise, leading to better signal quality and less distortion. It’s often expressed in decibels (dB). For example, an SNR of 30dB indicates that the signal power is 1000 times greater than the noise power. SNR is vital because it directly impacts the performance of communication and signal processing systems. Low SNR results in errors and unreliable communication; high SNR ensures reliable and accurate signal interpretation. The required SNR varies depending on the application; for instance, high-fidelity audio requires a much higher SNR than a basic voice communication system.

Q 6. What are some common challenges in wideband signal acquisition?

Acquiring wideband signals presents unique challenges:

- High sampling rates: Capturing wide bandwidths requires extremely fast analog-to-digital converters (ADCs), increasing cost and complexity.

- Synchronization: Maintaining precise timing across a wide frequency range can be difficult, particularly in multi-channel systems.

- Dynamic range: Wideband signals often exhibit a large dynamic range, requiring ADCs with high resolution to avoid signal clipping or distortion.

- Data storage and processing: The sheer volume of data generated by wideband acquisition requires significant storage capacity and powerful processing capabilities.

For instance, in radar systems, acquiring wideband signals allows for high-resolution imaging, but demands sophisticated signal processing techniques and powerful computing resources to handle the data deluge.

Q 7. How do you perform signal filtering in wideband and narrowband systems?

Signal filtering in wideband and narrowband systems relies on different techniques:

Narrowband filtering: Simple, fixed-frequency filters (like RC or LC filters) can effectively isolate narrowband signals. Digital filters (FIR or IIR) offer more flexibility, allowing for precise control of filter characteristics. A classic example is selecting a specific radio station using a narrowband filter in a radio receiver.

Wideband filtering: This often involves more sophisticated techniques like wavelet transforms, matched filtering, or adaptive filtering. Wavelet transforms decompose the wideband signal into different frequency components, allowing for selective filtering. Matched filtering optimally extracts a known signal from noise, even in a wideband scenario. Adaptive filters adjust their characteristics based on the input signal and noise, further enhancing performance in dynamic environments.

Q 8. Describe different types of filters used in signal processing.

Filters are fundamental in signal processing, allowing us to selectively pass or attenuate specific frequency components of a signal. They’re like sieves for frequencies. Different filter types are characterized by their frequency response, which describes how they affect different frequencies. Here are some common types:

- Low-pass filters: These allow low-frequency components to pass through while attenuating high-frequency components. Think of a bass filter in audio – it removes the high-pitched sounds.

- High-pass filters: These do the opposite, letting high-frequency signals pass and blocking low-frequency ones. Imagine a treble filter, emphasizing high-pitched sounds.

- Band-pass filters: These allow a specific range of frequencies to pass through, rejecting both lower and higher frequencies. Think of a radio tuner, selecting only the desired station’s frequency.

- Band-stop filters (or notch filters): These attenuate a specific range of frequencies, allowing frequencies outside that range to pass. This is useful for removing noise or interference at a particular frequency.

- Finite Impulse Response (FIR) filters: These are filters with a finite duration impulse response, meaning their output settles to zero after a finite time. They are often preferred due to their stability and linear phase response.

- Infinite Impulse Response (IIR) filters: These filters have an infinite duration impulse response, meaning their output theoretically continues indefinitely. They are computationally efficient but can exhibit instability if not designed carefully.

The choice of filter type depends heavily on the application. For example, in audio processing, you might use a low-pass filter to remove high-frequency hiss, while in image processing, a high-pass filter could enhance edges.

Q 9. Explain the Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem and its relevance to signal processing.

The Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem is a cornerstone of digital signal processing. It states that to accurately reconstruct a continuous-time signal from its discrete-time samples, the sampling frequency (fs) must be at least twice the highest frequency component (fmax) present in the signal. In simpler terms, you need to take samples at least twice as fast as the fastest oscillation in your signal.

Mathematically: fs ≥ 2fmax

This is crucial because if you sample too slowly (below the Nyquist rate, 2fmax), you risk aliasing, where high-frequency components masquerade as lower frequencies, leading to distortion in the reconstructed signal. Imagine trying to capture a fast-spinning wheel with a slow camera – the wheel might appear to be spinning slowly in the opposite direction.

In practice, this means that before digitizing an analog signal, we must either limit its bandwidth (remove high frequencies) using an anti-aliasing filter or increase the sampling rate sufficiently.

Q 10. What are the implications of aliasing in signal processing?

Aliasing, as mentioned earlier, is a severe consequence of undersampling. It occurs when high-frequency components in a signal are misrepresented as lower-frequency components during the sampling process. This leads to distortion and inaccuracy in the reconstructed signal. The high frequencies are essentially ‘folded’ into the lower frequencies, creating a false representation of the original signal.

Imagine a sound wave with a frequency above the Nyquist rate. When sampled, it will appear as a lower-frequency wave, resulting in a completely different sound. This can lead to errors in many applications such as audio processing, medical imaging, or communication systems. Preventing aliasing involves careful selection of sampling rate and the use of anti-aliasing filters, which attenuate frequencies above half the sampling rate before sampling.

Q 11. How do you perform spectral analysis of wideband signals?

Analyzing wideband signals, which contain a broad range of frequencies, requires specialized techniques because standard methods might be computationally expensive or inefficient. Here’s a breakdown:

- Downsampling/Decimation: Before analysis, the wideband signal is often downsampled to reduce computational burden. This involves reducing the sampling rate, but only after appropriate filtering to avoid aliasing.

- Goertzel Algorithm: This efficient algorithm can be used to calculate the DFT (Discrete Fourier Transform) for specific frequencies, making it suitable for analyzing specific frequency components of interest within a wideband signal.

- FFT (Fast Fourier Transform): While computationally intensive for very wideband signals, a segmented FFT approach is often used. This breaks the long wideband signal into smaller segments and then applies the FFT to each segment, followed by appropriate averaging or other signal processing methods to reconstruct the full spectrum. This reduces memory requirements and allows for parallel processing.

- Wavelet Transform: This time-frequency analysis technique can be helpful in capturing transient events and identifying frequency changes over time within wideband signals, offering better time-resolution than FFT for some applications.

The choice of technique depends on the characteristics of the signal, available computational resources, and the specific information needed from the analysis.

Q 12. Explain the concept of Fourier Transform and its applications in signal processing.

The Fourier Transform is a mathematical tool that decomposes a signal into its constituent frequencies. It essentially transforms a signal from the time domain (how the signal varies with time) to the frequency domain (how the signal’s energy is distributed across different frequencies). This is analogous to separating a musical chord into its individual notes.

The most common type is the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT), which is applied to discrete-time signals. The Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) is a highly efficient algorithm for computing the DFT.

Applications:

- Spectral Analysis: Identifying the frequencies present in a signal (e.g., identifying the frequencies of notes in music).

- Signal Filtering: Designing filters by manipulating the frequency components of a signal (e.g., removing noise from audio).

- Signal Compression: Reducing the size of a signal by discarding insignificant frequency components (e.g., MP3 compression).

- Image Processing: Analyzing and manipulating images in the frequency domain (e.g., image sharpening).

- Communications: Analyzing and decoding modulated signals in communication systems.

Q 13. What are some common applications of wideband signal analysis?

Wideband signal analysis finds applications in various fields where signals span a large frequency range. Examples include:

- Radar Systems: Analyzing radar returns to detect and track objects, identifying their range and velocity.

- Electronic Warfare: Identifying and classifying different emitters and signals from various sources.

- Cognitive Radio: Detecting available spectrum and dynamically adapting to utilize it.

- Seismology: Analyzing seismic data to understand the nature of earthquakes and other earth movements.

- Astronomy: Analyzing signals from telescopes to study astronomical phenomena.

In these scenarios, the wide bandwidth captures a richer picture of the environment or phenomenon under study. This allows for better discrimination of signals and extraction of more meaningful information.

Q 14. What are some common applications of narrowband signal analysis?

Narrowband signal analysis focuses on signals occupying a limited frequency range. Common applications include:

- Telecommunications: Analyzing signals within a specific channel in a communication system, such as a cellular network or radio broadcast.

- Biomedical Signal Processing: Analyzing ECG (electrocardiogram) or EEG (electroencephalogram) signals to diagnose heart or brain conditions, where specific frequencies relate to specific physiological phenomena.

- Power System Monitoring: Analyzing power line signals to detect faults and abnormalities.

- Acoustic Signal Processing: Analyzing speech signals or other narrowband audio sources for voice recognition, noise reduction, or other applications.

- Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS): Processing signals from satellites to determine location.

In these cases, the narrowband nature allows for precise measurements and filtering of unwanted noise or interference within the specific band of interest. This increases the signal-to-noise ratio, making it easier to extract relevant information.

Q 15. Explain the concept of time-frequency analysis and its use in signal processing.

Time-frequency analysis is a crucial signal processing technique that reveals how the frequency content of a signal changes over time. Imagine listening to an orchestra: you can hear different instruments playing at different times and with different pitches. Time-frequency analysis allows us to similarly decompose a signal into its constituent frequencies as they evolve over time, providing a much richer understanding than simply looking at the frequency spectrum alone (which shows only the overall frequencies present). This is particularly valuable for non-stationary signals – signals whose frequency content changes over time, which are incredibly common in real-world applications.

Its uses are vast, encompassing areas like speech recognition (identifying phonemes), radar signal processing (detecting moving targets), medical diagnostics (analyzing EEG or ECG signals), and seismic analysis (identifying earthquake characteristics).

Career Expert Tips:

- Ace those interviews! Prepare effectively by reviewing the Top 50 Most Common Interview Questions on ResumeGemini.

- Navigate your job search with confidence! Explore a wide range of Career Tips on ResumeGemini. Learn about common challenges and recommendations to overcome them.

- Craft the perfect resume! Master the Art of Resume Writing with ResumeGemini’s guide. Showcase your unique qualifications and achievements effectively.

- Don’t miss out on holiday savings! Build your dream resume with ResumeGemini’s ATS optimized templates.

Q 16. Describe different time-frequency analysis techniques, such as STFT and wavelet transform.

Several techniques achieve time-frequency analysis. Two prominent ones are:

- Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT): This method works by dividing the signal into small, overlapping time windows. A Fourier Transform is then applied to each window, providing a frequency spectrum for that specific time interval. Think of it like taking snapshots of the frequency content at different points in time. The resolution is limited by the window size: a shorter window offers better time resolution but poorer frequency resolution, and vice versa. This is the time-frequency uncertainty principle.

- Wavelet Transform: Wavelets are small, wave-like functions with varying frequencies and durations. The wavelet transform analyzes a signal by convolving it with a set of wavelets at different scales (frequencies) and locations (time). It adapts the window size to better resolve both frequency and time information, which is superior to STFT for signals with transient events, where short bursts of high-frequency content are important. For example, analyzing a heart beat where the exact timing of a specific frequency component is critical.

Choosing between STFT and Wavelet Transform depends on the signal’s characteristics. If the signal has relatively stationary frequency components, STFT might suffice. However, for signals with sharp transitions or transient features, the wavelet transform provides a significant advantage.

Q 17. How do you perform signal detection and estimation in noisy environments?

Signal detection and estimation in noisy environments are fundamental challenges in signal processing. The goal is to extract the desired signal from a background of unwanted noise. We typically use statistical signal processing techniques that leverage the differences in statistical properties between the signal and the noise. A common approach is to model both the signal and the noise statistically, often assuming Gaussian noise. Then, we can use optimal detection or estimation theories such as the Neyman-Pearson criterion or Minimum Mean Square Error (MMSE) estimation.

Techniques often involve filtering, where we design filters to pass the signal while attenuating the noise (based on their different frequency characteristics, for instance, using bandpass filters). Additionally, we can use signal averaging or other forms of ensemble averaging to improve the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). These techniques work better when multiple repetitions of the signal are available or the noise is uncorrelated from sample to sample.

Q 18. Explain different signal detection methods, such as matched filtering and energy detection.

Several signal detection methods exist, each with strengths and weaknesses:

- Matched Filtering: This is an optimal detection method when the signal is known exactly, and the noise is additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN). It correlates the received signal with a template of the expected signal. The peak of the correlation indicates the presence of the signal. Imagine searching for a specific song in a noisy environment – matched filtering is like having a perfect audio template to compare against. It’s computationally efficient but assumes perfect knowledge of the signal, which is often not the case in real-world scenarios.

- Energy Detection: This simpler method sums the squared magnitudes of the received signal over a certain time interval. If the energy exceeds a threshold, the signal is declared present. It’s computationally inexpensive and doesn’t require knowledge of the signal’s shape, but it’s less efficient and more prone to false alarms in low SNR environments.

The choice between matched filtering and energy detection often depends on the available signal knowledge and the computational constraints.

Q 19. What are the challenges in processing signals with multipath propagation?

Multipath propagation, where the transmitted signal takes multiple paths to reach the receiver, creates significant challenges in signal processing. These challenges include:

- Inter-Symbol Interference (ISI): Delayed signal copies overlap with subsequent signals, blurring the received signal and making it difficult to discern individual symbols. This is akin to hearing echoes that overlap with the original sound.

- Signal Fading: Constructive and destructive interference between multiple paths can lead to significant variations in signal strength, making reliable communication difficult. This is similar to the variations in radio signal strength you might experience as you drive.

- Increased complexity: Dealing with multiple paths necessitates more sophisticated signal processing techniques to counteract the effects of multipath.

These challenges impact data rates, error rates, and the overall reliability of communication systems.

Q 20. How do you compensate for multipath effects in signal processing?

Several techniques compensate for multipath effects:

- Equalization: This technique attempts to counteract the ISI introduced by multipath by applying a filter that inverts the channel response. This can involve adaptive algorithms that adjust the filter coefficients based on the received signal.

- Diversity techniques: Using multiple antennas (spatial diversity) or transmitting on multiple frequencies (frequency diversity) allows the receiver to exploit independent signal paths and mitigate fading effects.

- Channel estimation: Accurate channel characterization is crucial for effective multipath compensation. Techniques such as pilot-symbol assisted modulation or blind channel estimation help estimate the channel response, which then informs the design of equalization filters.

- RAKE receiver: This type of receiver correlates the received signal with replicas of the transmitted signal at different delays, thereby combining the energy from various signal paths constructively.

The optimal approach depends on factors like the channel characteristics, the available resources, and the performance requirements.

Q 21. Explain the concept of channel equalization and its importance in communication systems.

Channel equalization is a crucial signal processing technique used to mitigate the effects of Inter-Symbol Interference (ISI) in communication systems. ISI arises when multiple versions of a transmitted signal arrive at the receiver with varying delays, caused by multipath propagation. Equalization aims to restore the original transmitted signal by compensating for the distortion introduced by the channel. Imagine sending a message through a distorted telephone line – equalization is like applying a filter to clean up the sound and make it intelligible.

Its importance lies in its ability to improve the performance of communication systems in real-world environments. Without equalization, ISI would severely limit data rates and increase bit error rates, making reliable communication impossible in most scenarios. Various equalization techniques exist, from simple linear equalizers to sophisticated adaptive algorithms such as Least Mean Squares (LMS) and Recursive Least Squares (RLS), each offering trade-offs between complexity and performance.

Q 22. Describe different channel equalization techniques.

Channel equalization is crucial in communication systems to compensate for distortions introduced by the channel, ensuring reliable data transmission. Different techniques exist, each with its strengths and weaknesses depending on the channel characteristics and computational resources.

- Linear Equalization: This is a simple and widely used technique where a filter is designed to inverse the channel’s frequency response. This is effective for channels with mild distortions. A common example is the Zero-Forcing Equalizer (ZFE), which directly inverts the channel response. However, it can amplify noise significantly if the channel has deep fades.

- Decision Feedback Equalization (DFE): This technique uses previous decisions to improve the current estimate. It’s especially useful for channels with intersymbol interference (ISI), where the effect of one symbol bleeds into subsequent symbols. The feedback section subtracts the interference from previous symbols, enhancing accuracy. DFEs are robust and widely used in high-speed communication systems like DSL.

- Adaptive Equalization: Channel characteristics often change dynamically (e.g., due to fading in wireless systems). Adaptive equalizers continuously adjust their parameters based on the received signal, tracking these changes. The Least Mean Squares (LMS) algorithm is a popular choice for adaptive equalization due to its simplicity and ease of implementation. It iteratively adjusts the equalizer coefficients to minimize the error between the received and desired signals. Recursive Least Squares (RLS) is another adaptive algorithm offering faster convergence but higher computational complexity.

- Maximum Likelihood Sequence Estimation (MLSE): MLSE is a powerful technique that finds the most likely sequence of transmitted symbols given the received signal. It considers all possible symbol sequences and selects the one with the highest probability. This provides optimal performance in terms of minimizing error but often involves high computational cost, limiting its practicality in high-speed applications.

The choice of equalization technique depends on factors like channel characteristics (e.g., ISI severity, frequency response), computational constraints, and the desired performance level. In many real-world scenarios, a combination of techniques might be employed to achieve optimal results.

Q 23. What are the key performance indicators (KPIs) for evaluating the performance of a communication system?

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for a communication system evaluate its effectiveness and efficiency. These KPIs often depend on the specific application, but some common ones include:

- Bit Error Rate (BER): The ratio of incorrectly received bits to the total number of transmitted bits. Lower BER indicates better performance.

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): Measures the strength of the desired signal relative to the noise. Higher SNR usually implies better reliability.

- Spectral Efficiency: The amount of information transmitted per unit bandwidth. Higher spectral efficiency is desirable to maximize data throughput within limited frequency resources.

- Throughput: The actual amount of data successfully transmitted over a period. It’s affected by BER and other factors.

- Latency: The delay experienced between sending and receiving data. Low latency is crucial for real-time applications.

- Power Consumption: Important for mobile and battery-powered devices. Lower power consumption allows for longer operation.

Consider a cellular network: A low BER is critical for reliable call quality and data transmission. High spectral efficiency ensures many users can access the network simultaneously. Latency becomes crucial for applications like online gaming, while power consumption is a primary concern for cell phones.

Q 24. How do you design and implement a signal processing algorithm for a specific application?

Designing a signal processing algorithm starts with a clear understanding of the application’s requirements and constraints. The process typically follows these steps:

- Problem Definition: Precisely define the problem. For instance, is it noise reduction, signal detection, or feature extraction?

- Data Analysis: Analyze the available data to understand its characteristics (e.g., noise levels, signal properties). Statistical methods and visualizations are helpful here.

- Algorithm Selection: Choose an appropriate algorithm based on the problem, data characteristics, and computational constraints. Consider the trade-offs between performance and complexity.

- Algorithm Implementation: Implement the algorithm using a suitable programming language and software tools (e.g., MATLAB, Python). This may involve using existing libraries or writing custom code.

- Testing and Validation: Thoroughly test the algorithm using both simulated and real-world data. Evaluate its performance using relevant KPIs (e.g., BER, SNR).

- Optimization: Refine the algorithm to improve performance, reduce complexity, or optimize resource usage.

For example, designing an algorithm for speech enhancement involves analyzing the characteristics of speech and noise, selecting a suitable noise reduction technique (e.g., spectral subtraction, Wiener filtering), implementing the chosen technique, and testing its performance using objective measures like the signal-to-noise ratio improvement and subjective listening tests.

Q 25. Explain your experience with different signal processing software tools (e.g., MATLAB, Python).

I have extensive experience using MATLAB and Python for signal processing tasks. MATLAB provides excellent built-in functions and toolboxes for signal analysis, filtering, and system design. I’ve used it for tasks like designing FIR/IIR filters, performing spectral analysis using FFT, and implementing various modulation/demodulation schemes. For example, I designed an adaptive equalizer in MATLAB for a wireless communication system, evaluating its performance using simulated fading channels. Python, with libraries like NumPy, SciPy, and matplotlib, offers flexibility and powerful data manipulation capabilities. I prefer Python for tasks requiring more customized data processing, statistical analysis, and algorithm prototyping. I’ve used Python to develop a real-time audio processing application, creating custom filters and analyzing spectrograms.

Q 26. How do you troubleshoot problems in a signal processing system?

Troubleshooting a signal processing system involves a systematic approach:

- Identify the Problem: Precisely define the problem. Is it low signal quality, high error rate, unexpected behavior, or something else?

- Examine the Data: Analyze the input and output signals to pinpoint where the issue originates. Visualizing the data (e.g., using time-domain and frequency-domain plots) is often crucial.

- Check the Algorithm: Verify the algorithm’s correctness by comparing its output to expected results. Step-by-step debugging and code reviews can help.

- Verify Hardware: Ensure all hardware components are functioning correctly. Check connections, sample rates, and any other relevant parameters.

- Isolate the Issue: Systematically isolate the problem by testing different parts of the system. Divide and conquer is a valuable strategy.

- Document the Solution: Document the issue, the troubleshooting process, and the solution for future reference.

For instance, if a communication system has a high BER, I would start by checking the signal quality at various points in the system, examine the equalizer performance, investigate hardware components (e.g., ADC/DAC), and potentially refine the algorithm or parameters.

Q 27. Describe your experience with hardware related to signal processing.

My experience with signal processing hardware includes working with various Analog-to-Digital Converters (ADCs), Digital-to-Analog Converters (DACs), Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs), and Digital Signal Processors (DSPs). I’ve worked on projects involving the design and implementation of high-speed data acquisition systems, real-time signal processing using FPGAs for low-latency applications, and the use of DSPs for computationally intensive tasks. For example, I used an FPGA to implement a real-time adaptive filter for noise cancellation in an audio processing application, optimizing for speed and power consumption. I also have experience with software defined radios (SDRs), configuring them for various communication applications.

Q 28. Discuss your experience with different types of antennas and their applications.

I have experience with various antenna types and their applications. My knowledge encompasses:

- Dipole Antennas: Simple, resonant antennas widely used in many applications, like radio broadcasting and amateur radio.

- Patch Antennas: Planar antennas useful for applications requiring compact size, such as mobile phones and wireless communication devices. I worked on a project integrating a microstrip patch antenna into a wireless sensor node.

- Yagi-Uda Antennas: Directional antennas offering high gain and directivity, often used in television reception and point-to-point communication links.

- Horn Antennas: Used in applications requiring high gain and a well-defined beam shape, for instance, in satellite communications and radar systems.

- Microstrip Antennas: Planar antennas fabricated using printed circuit board (PCB) technology, suitable for integration into compact devices.

The choice of antenna depends heavily on factors like frequency range, required gain, directivity, size constraints, and application environment. For example, in a cellular network, base stations often employ high-gain antennas to maximize coverage area, while mobile phones use compact antennas with relatively lower gain due to space limitations.

Key Topics to Learn for Wideband and Narrowband Signals Analysis Interview

- Signal Characteristics: Understanding the differences between wideband and narrowband signals, including bandwidth, frequency content, and time-domain representations. Explore concepts like spectral density and signal power.

- Signal Processing Techniques: Mastering techniques for analyzing both wideband and narrowband signals, such as filtering (e.g., low-pass, high-pass, band-pass), Fourier transforms (FFT), and time-frequency analysis (e.g., spectrograms, wavelet transforms).

- Modulation and Demodulation: Familiarize yourself with various modulation schemes (e.g., AM, FM, QAM) and their impact on signal bandwidth and characteristics. Understand the principles of demodulation and signal recovery.

- Noise and Interference: Learn about different types of noise (e.g., thermal noise, shot noise) and their effects on signal quality. Understand techniques for noise reduction and interference mitigation.

- Practical Applications: Explore real-world applications of wideband and narrowband signal analysis, such as in telecommunications (cellular networks, satellite communication), radar systems, medical imaging, and audio processing. Consider how these applications influence signal analysis choices.

- System Design Considerations: Understand the trade-offs involved in designing systems that process wideband and narrowband signals, including hardware limitations, power consumption, and computational complexity.

- Problem-Solving Approach: Practice systematically approaching signal analysis problems. This includes defining the problem, selecting appropriate tools and techniques, interpreting results, and drawing meaningful conclusions.

Next Steps

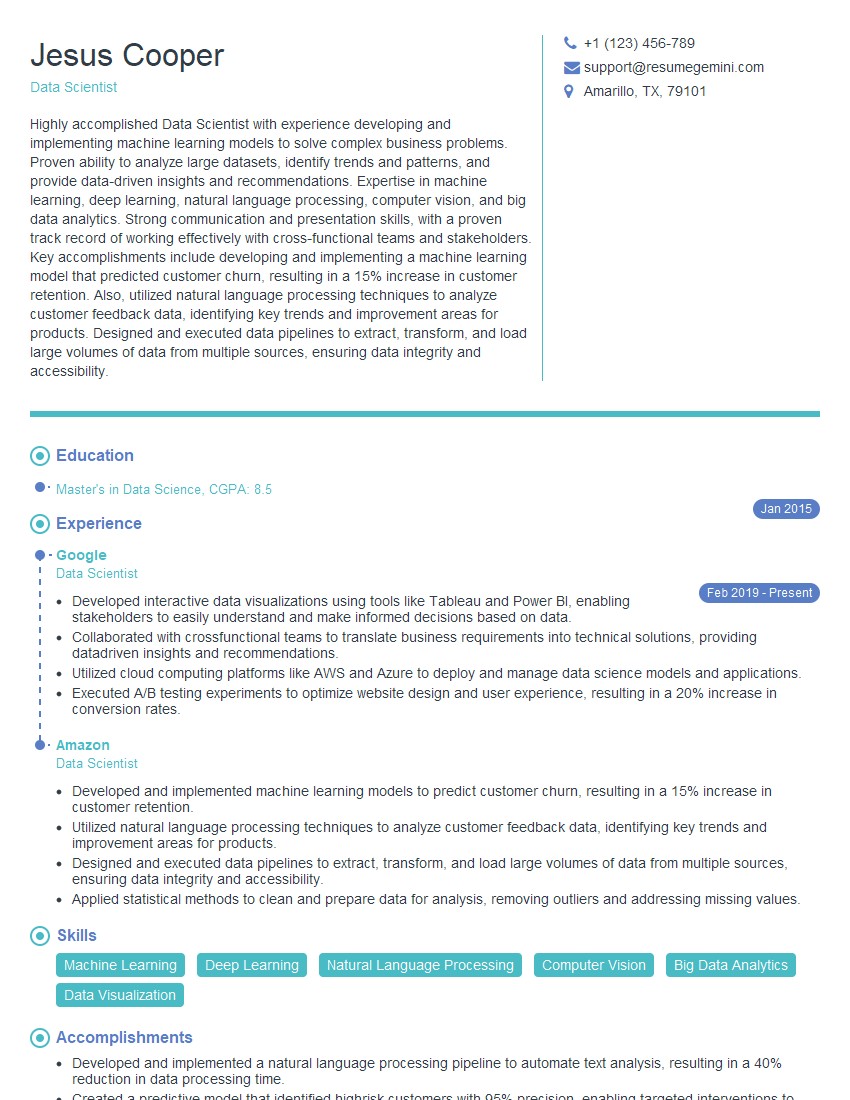

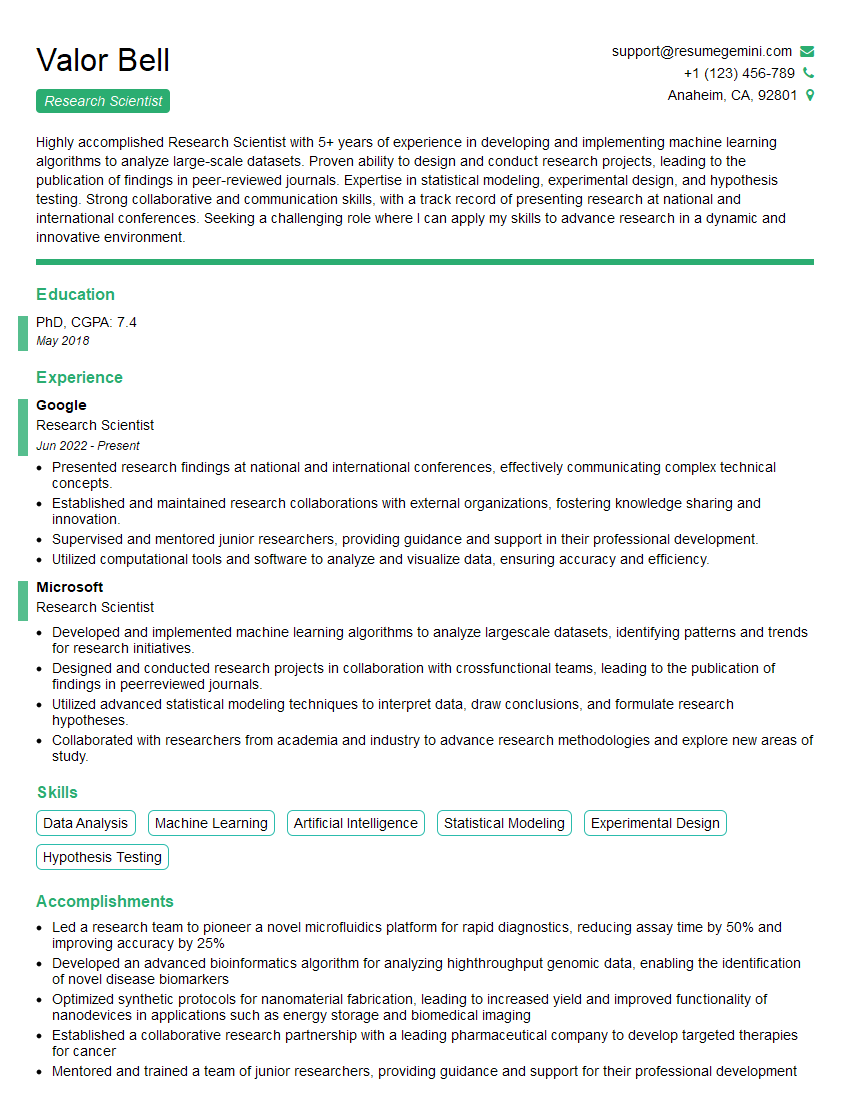

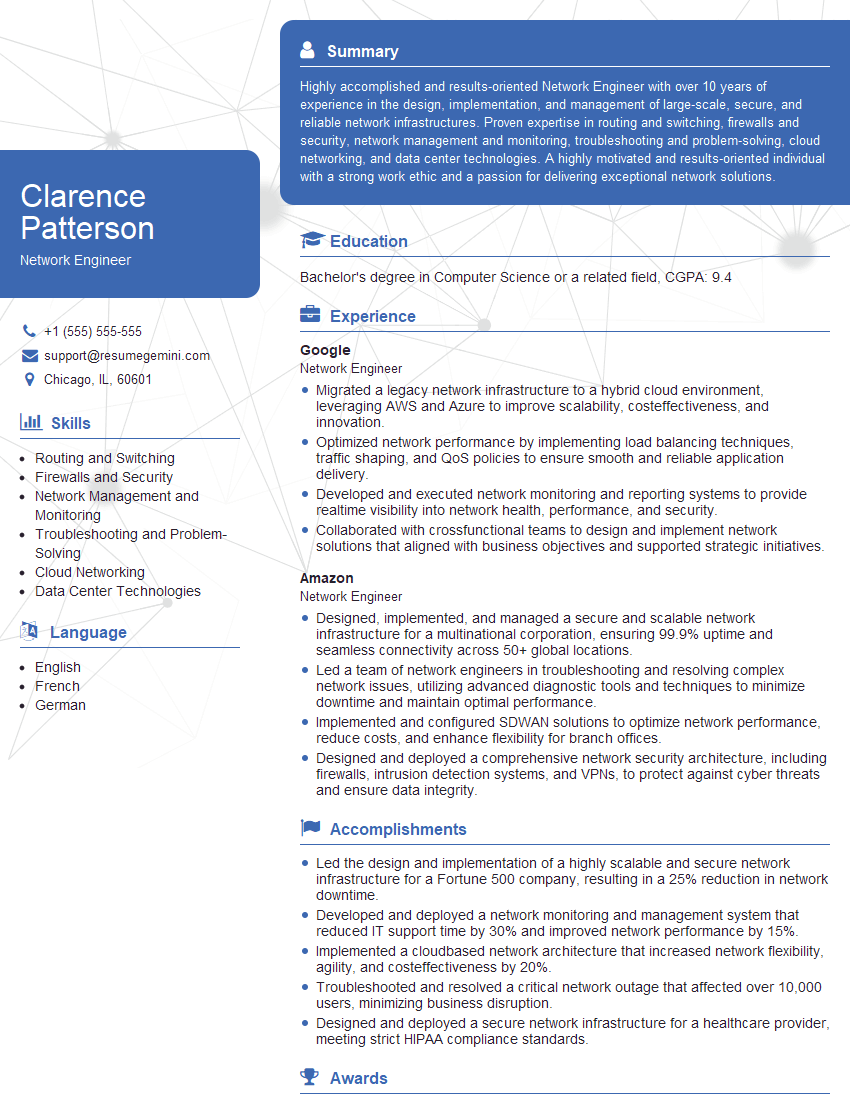

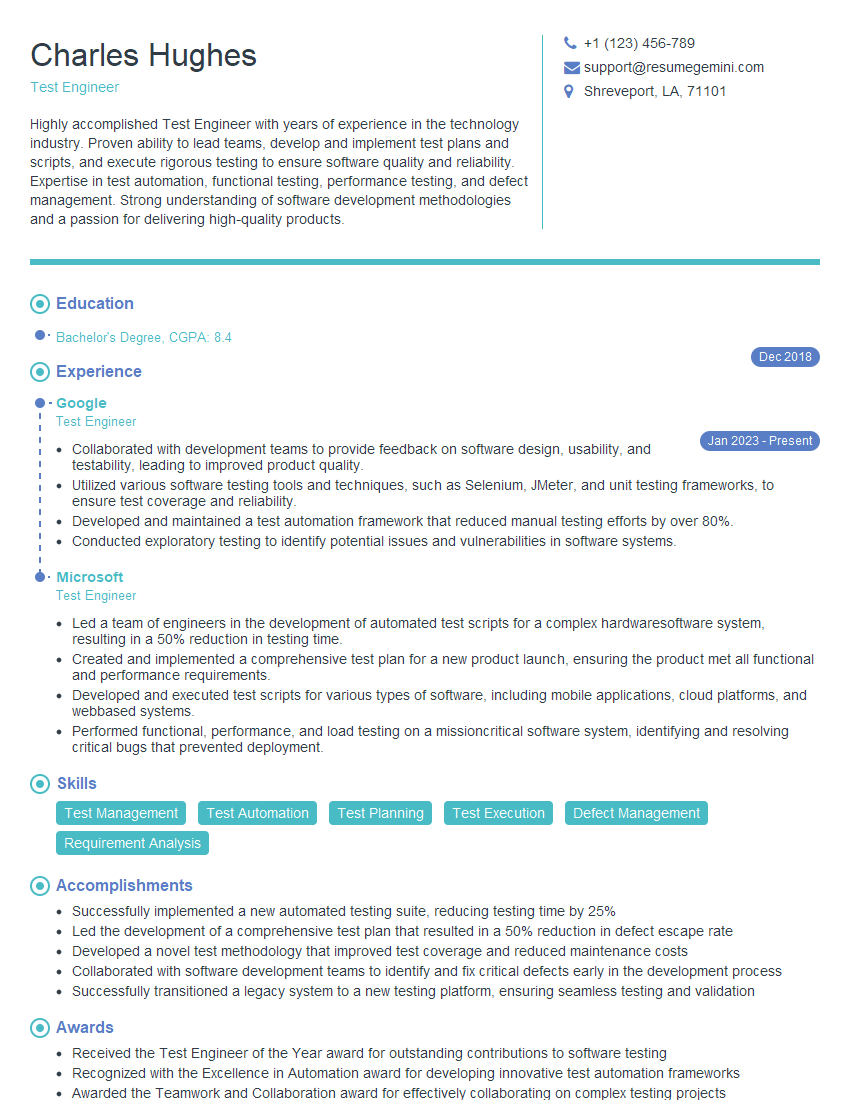

Mastering Wideband and Narrowband Signals Analysis is crucial for a successful career in various engineering and scientific fields. A strong understanding of these concepts opens doors to exciting opportunities and demonstrates a valuable skill set to potential employers. To maximize your job prospects, it’s vital to present your skills effectively. Crafting an ATS-friendly resume is key to getting your application noticed. ResumeGemini is a trusted resource that can significantly enhance your resume-building experience, helping you showcase your expertise in a way that resonates with recruiters. Examples of resumes tailored to Wideband and Narrowband Signals Analysis are available to help guide you.

Explore more articles

Users Rating of Our Blogs

Share Your Experience

We value your feedback! Please rate our content and share your thoughts (optional).

What Readers Say About Our Blog

To the interviewgemini.com Webmaster.

Very helpful and content specific questions to help prepare me for my interview!

Thank you

To the interviewgemini.com Webmaster.

This was kind of a unique content I found around the specialized skills. Very helpful questions and good detailed answers.

Very Helpful blog, thank you Interviewgemini team.