Are you ready to stand out in your next interview? Understanding and preparing for Ethics in Ethnographic Research interview questions is a game-changer. In this blog, we’ve compiled key questions and expert advice to help you showcase your skills with confidence and precision. Let’s get started on your journey to acing the interview.

Questions Asked in Ethics in Ethnographic Research Interview

Q 1. Define informed consent in the context of ethnographic research.

Informed consent in ethnographic research means participants are fully aware of the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks and benefits, and their right to withdraw at any time without penalty. It’s not just a signature on a form; it’s an ongoing process of communication and respect for participants’ autonomy.

Think of it like this: imagine you’re inviting someone into your home. You’d explain why you want them to visit, what you’ll be doing together, and assure them they’re free to leave whenever they feel uncomfortable. Informed consent in research is the same, but with the added layer of protecting their privacy and data.

Ethnographic research often involves long-term engagement, so informed consent needs to be revisited and reaffirmed throughout the project. This might involve regular check-ins, allowing participants to express concerns, and adapting the research plan as needed based on their feedback.

Q 2. Explain the concept of cultural relativism and its ethical implications.

Cultural relativism is the principle of understanding a culture on its own terms, without imposing your own cultural values or judgments. It’s crucial for ethical ethnographic research because it encourages researchers to avoid ethnocentrism—the tendency to view other cultures through the lens of one’s own culture.

The ethical implications are significant. Without cultural relativism, researchers risk misinterpreting data, imposing harmful interventions, and perpetuating harmful stereotypes. For example, a practice that might seem strange or even ‘wrong’ to an outsider could have a perfectly logical and valuable function within its cultural context. The researcher’s job is to understand that context, not judge it.

However, cultural relativism doesn’t imply moral relativism. Just because a practice is culturally accepted doesn’t mean it’s ethically acceptable. A researcher must navigate the complex interplay between understanding and ethical responsibility.

Q 3. How do you ensure anonymity and confidentiality in your ethnographic research?

Ensuring anonymity and confidentiality is paramount. Anonymity means participants’ identities are never revealed, even to the researcher. Confidentiality means the researcher protects participants’ information from unauthorized access. This requires careful planning and execution.

- Data Collection: Use pseudonyms instead of real names. Avoid collecting identifying information unless absolutely necessary and justified.

- Data Storage: Securely store data, using password-protected files and encrypted storage solutions. Limit access to the data to only authorized personnel.

- Data Analysis: Employ methods that protect anonymity during analysis. For example, aggregate data to prevent individual identification.

- Reporting: Do not include any identifying information in research reports or publications. When presenting findings, always focus on patterns and trends, not individual cases.

Imagine you are studying a community’s response to a natural disaster. You can report on the community’s resilience without revealing the identities of any individuals affected.

Q 4. Describe the process of obtaining IRB approval for an ethnographic study.

Obtaining Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval is a crucial step in ethical ethnographic research. The IRB is a committee that reviews research proposals to ensure they meet ethical standards and protect human subjects.

The process typically involves:

- Developing a detailed research proposal: This includes the research question, methodology, informed consent procedures, data analysis plan, and a risk assessment.

- Submitting the proposal to the IRB: The proposal is reviewed by IRB members, who assess the ethical implications of the research.

- Addressing IRB feedback: The IRB may request revisions to the proposal to address concerns about ethical issues. This is an iterative process.

- Receiving IRB approval: Once the IRB is satisfied that the research meets ethical standards, it grants approval for the study to proceed.

The IRB approval process ensures that the research is conducted ethically and protects the rights and well-being of participants.

Q 5. What are the ethical considerations when working with vulnerable populations?

Working with vulnerable populations—children, the elderly, individuals with disabilities, or those experiencing poverty or marginalization—requires heightened ethical sensitivity. These populations may be more susceptible to coercion or exploitation.

Ethical considerations include:

- Additional safeguards: Obtaining informed consent may require extra steps, such as involving guardians or advocates.

- Power dynamics: Be acutely aware of power imbalances and actively mitigate any potential for exploitation. Building trust and rapport is crucial.

- Potential for harm: Carefully assess potential risks to participants and implement strategies to minimize harm. Consider the potential impact of the research on their lives and their communities.

- Beneficence: Ensure that the research benefits the community and contributes to their well-being. This may involve collaborations that support community needs.

For instance, when studying children, gaining parental or guardian consent is paramount, and research activities must be age-appropriate and non-invasive.

Q 6. How do you address potential conflicts of interest in your research?

Conflicts of interest can arise when researchers’ personal interests, financial gains, or relationships could compromise the objectivity and integrity of their research. Transparency and careful planning are key to addressing this.

Steps to address potential conflicts of interest include:

- Disclosure: Clearly disclose any potential conflicts of interest to the IRB and any relevant stakeholders.

- Mitigation strategies: Develop strategies to minimize or eliminate any potential conflicts. This may involve recusal from certain decisions or employing independent reviewers.

- Objectivity: Maintain objectivity throughout the research process, ensuring that personal biases do not influence data collection, analysis, or interpretation.

- Independent review: Seek independent review of the research findings to ensure objectivity and validity.

For example, if a researcher is funded by an organization that has a vested interest in the research outcome, this must be disclosed transparently to avoid bias.

Q 7. Explain the concept of reflexivity in ethnographic research and its ethical relevance.

Reflexivity in ethnographic research involves critically examining your own positionality, biases, and assumptions, and how they might influence the research process and findings. It’s an ethical imperative because it acknowledges that researchers are not neutral observers; their perspectives inevitably shape the research.

Ethical relevance stems from the recognition that researchers’ identities and experiences—their background, beliefs, and relationships—can shape their interactions with participants and their interpretations of data. Without reflexivity, researchers risk imposing their own worldview on the culture they study. For example, a researcher’s prior experiences with poverty might unconsciously influence how they interpret a community’s struggles.

Reflexivity is an ongoing process that involves self-reflection, journaling, peer review, and potentially, engaging in collaborative analysis with community members. By acknowledging biases, researchers can strive for more accurate, nuanced, and ethical representations of the cultures they study.

Q 8. How do you navigate ethical dilemmas that arise during fieldwork?

Ethical dilemmas in fieldwork are inevitable. Navigating them requires a proactive and reflexive approach. I prioritize ethical considerations from the outset, beginning with informed consent procedures. This means clearly explaining the research aims, methods, risks, and benefits to participants in a language they understand, ensuring they feel empowered to withdraw at any point. If a dilemma arises, I employ a reflective framework involving several steps:

- Pause and Reflect: I take time to carefully consider the situation, identifying the conflicting values and potential consequences of different actions.

- Consult: I discuss the dilemma with my research supervisor, ethics committee, or colleagues, seeking diverse perspectives.

- Consider Participant Well-being: The well-being of my participants always takes precedence. I ask myself: ‘What action best protects their interests and rights?’

- Document: I meticulously document the dilemma, my deliberations, and the chosen course of action, along with justifications. This is crucial for accountability and transparency.

- Adapt and Learn: I review my actions afterward, considering what I learned from the experience and how I might better address similar situations in the future.

For example, during fieldwork in a rural community, I faced a dilemma when observing a potentially illegal activity. Following my reflective framework, I decided against direct intervention but informed my supervisor and the ethics committee, ultimately modifying my research plan to avoid further involvement in the situation while still gathering relevant data ethically.

Q 9. What are the ethical considerations related to data storage and security?

Data storage and security are paramount. Ethical considerations revolve around confidentiality, anonymity, and data protection. I follow rigorous procedures to ensure participant privacy and data security. This starts with anonymizing data whenever possible, replacing identifying information with codes or pseudonyms. I use secure storage methods, including password-protected files, encrypted hard drives, and secure cloud storage services with robust access controls. Furthermore, I adhere to data protection regulations (like GDPR or HIPAA, depending on location and context) and obtain necessary consent for data usage and storage.

For instance, I might use software with data encryption features like AES-256 to protect sensitive information. Access to the data is restricted to myself and my supervisor, and any shared data is further protected through secure file-sharing platforms. Data is stored securely and only for the duration necessary for the research.

Q 10. How do you ensure the responsible use of technology in ethnographic research?

Responsible technology use in ethnography demands careful consideration. Technology offers amazing opportunities for data collection and analysis but also presents unique ethical challenges. For example, using recording devices requires explicit consent and transparency about their use. Similarly, online ethnography raises issues regarding informed consent, privacy, and online safety. My approach involves:

- Transparency: Clearly communicate with participants about the technology used, its purpose, and data management protocols.

- Consent: Obtain explicit consent for all forms of technological data collection, including audio and video recording, screenshots, and online interactions.

- Data Security: Employ secure methods to store and manage digital data, using encryption and access controls.

- Minimizing Risk: Be mindful of potential risks associated with technology, such as data breaches or online harassment, and take steps to mitigate them.

- Ethical Considerations for AI: If using AI for data analysis, ensure fairness, transparency, and accountability in its application, avoiding bias and misrepresentation.

For example, when using social media data, I ensure I’m only analyzing publicly available information and clearly state this in my research methodology. I avoid collecting or analyzing personal data without explicit permission.

Q 11. Describe your understanding of ethical guidelines for data analysis and interpretation.

Ethical data analysis and interpretation are guided by principles of honesty, accuracy, and fairness. This includes acknowledging limitations, avoiding biases, and presenting findings in a responsible and transparent manner. Key aspects are:

- Reflexivity: Reflect critically on my own biases and assumptions that may influence data interpretation.

- Transparency: Clearly describe data analysis methods used, making the process replicable and verifiable.

- Accuracy: Present data accurately, avoiding misrepresentation or selective reporting.

- Contextualization: Interpret data within the social and cultural context of the research setting.

- Respect for Participants: Ensure that data analysis and interpretation respect the dignity and autonomy of participants, avoiding harmful generalizations or stereotyping.

For example, if I find unexpected patterns in my data, I wouldn’t selectively present only the results that confirm my hypotheses. Instead, I’d acknowledge the unexpected findings, analyze their potential meanings, and explore alternative explanations.

Q 12. How do you manage power dynamics in researcher-participant relationships?

Power dynamics are inherent in researcher-participant relationships. The researcher holds considerable power through their role and access to resources. Mitigating this power imbalance is crucial for ethical research. My strategy involves:

- Building Rapport: Developing trust and rapport with participants through respectful communication, active listening, and demonstrating genuine interest in their perspectives.

- Shared Ownership: Involving participants in the research process, seeking their input on the research design and findings.

- Reciprocity: Giving something back to the community, such as sharing research findings or contributing to local initiatives.

- Transparency: Openly communicating the research aims, methods, and limitations.

- Respectful Communication: Always treating participants with respect and dignity, acknowledging their expertise and knowledge.

For instance, I might offer participants the opportunity to review and comment on my research report before dissemination. This acknowledges their agency and gives them a voice in how their stories are presented.

Q 13. How do you address potential biases in your ethnographic research?

Addressing biases is crucial for trustworthy research. Bias can creep into every stage, from research design to data interpretation. My approach involves:

- Self-Reflection: Regularly reflecting on my own biases and assumptions, understanding how they might influence my research.

- Triangulation: Using multiple data sources and methods to corroborate findings and reduce reliance on a single perspective.

- Peer Review: Seeking feedback from colleagues to identify potential biases in my analysis and interpretation.

- Critical Engagement: Engaging critically with the literature and existing theories to avoid replicating existing biases.

- Member Checking: Sharing findings with participants to seek their feedback and ensure accurate representation of their experiences.

For example, if my initial analysis suggests a particular trend, I might seek out participants with different viewpoints to ensure a comprehensive understanding and avoid making generalizations based on limited data.

Q 14. What strategies do you use to ensure the trustworthiness and validity of your research findings?

Trustworthiness and validity are essential for rigorous ethnographic research. I employ several strategies to enhance these aspects:

- Prolonged Engagement: Spending sufficient time in the field to develop deep understanding and build rapport with participants.

- Triangulation: Using multiple data sources (e.g., interviews, observations, documents) to corroborate findings.

- Peer Debriefing: Discussing findings and interpretations with colleagues to ensure objectivity.

- Member Checking: Sharing findings with participants for feedback and validation.

- Thick Description: Providing rich and detailed descriptions of the research context and participants’ experiences.

- Reflexivity: Reflecting on my own role and biases in the research process.

- Audit Trail: Maintaining a detailed record of the research process, including data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

For instance, I might use prolonged engagement to establish trust and fully understand the cultural nuances of a community, then utilize member checking to validate my interpretations and ensure accurate representation of their perspectives.

Q 15. Explain the difference between beneficence and non-maleficence in ethnographic research.

In ethnographic research, beneficence and non-maleficence are two crucial ethical principles focusing on the well-being of participants. Beneficence refers to actively promoting the well-being of participants. This means researchers should strive to maximize the benefits of their research for the community being studied. This could involve sharing research findings in a way that benefits the community, or working with the community to address identified needs. Non-maleficence, conversely, focuses on avoiding harm to participants. This means researchers must minimize any potential risks associated with the research, such as emotional distress, social stigma, or economic disadvantage. They must avoid causing any harm, physical or psychological, during the research process.

Think of it this way: beneficence is about doing good, while non-maleficence is about avoiding harm. A researcher might demonstrate beneficence by helping the community gain access to resources or influencing policy based on their research findings. Non-maleficence would be demonstrated by ensuring participant anonymity, protecting sensitive information, and being mindful of the potential emotional impact of the research questions.

Career Expert Tips:

- Ace those interviews! Prepare effectively by reviewing the Top 50 Most Common Interview Questions on ResumeGemini.

- Navigate your job search with confidence! Explore a wide range of Career Tips on ResumeGemini. Learn about common challenges and recommendations to overcome them.

- Craft the perfect resume! Master the Art of Resume Writing with ResumeGemini’s guide. Showcase your unique qualifications and achievements effectively.

- Don’t miss out on holiday savings! Build your dream resume with ResumeGemini’s ATS optimized templates.

Q 16. How do you balance the researcher’s need for information with the participant’s right to privacy?

Balancing the researcher’s need for information with a participant’s right to privacy is a central ethical challenge in ethnographic research. It requires a delicate balance of transparency and confidentiality. Before beginning the research, researchers must obtain informed consent from participants, clearly explaining the study’s purpose, methods, potential risks and benefits, and how their data will be used and protected. This includes detailing how anonymity and confidentiality will be ensured. Researchers should use pseudonyms or anonymizing techniques in their publications and data storage. Furthermore, data should be securely stored and accessed only by authorized individuals. It’s also crucial to be sensitive to the cultural context. What constitutes ‘private’ information can vary greatly across cultures.

For instance, if studying a close-knit community, observing public events might still reveal sensitive personal information inadvertently. Researchers must anticipate this and actively seek to minimize the disclosure of private information, even in seemingly public settings. They should always be prepared to adjust their research methods to respect participant boundaries and preferences.

Q 17. What is the role of reciprocity in ethnographic research?

Reciprocity is a core ethical principle in ethnographic research emphasizing the mutual exchange of benefits between the researcher and the participants. It’s not simply about giving participants something in return for their time and participation; it’s about building a relationship of trust and mutual respect based on fairness and collaboration. This might involve sharing research findings with the community, contributing to community projects, or offering participants something of value in return for their participation (e.g., a small gift, access to services, or even just a heartfelt thank you).

The form of reciprocity should be thoughtfully determined in consultation with the community, reflecting their needs and values. For example, in one study, I worked with a community by helping them produce a documentary film showcasing their cultural heritage after completing my research—this was a form of reciprocity mutually agreed upon. Failing to engage in meaningful reciprocity can damage trust and compromise the quality of the research by limiting access to information.

Q 18. Describe a situation where you had to make an ethical decision during fieldwork. What was the decision and what was its rationale?

During fieldwork studying a community grappling with environmental displacement, I witnessed an incident where a participant disclosed a significant personal vulnerability relating to their mental health that wasn’t directly related to the research topic. The participant implied suicidal ideation. I was faced with a critical ethical dilemma. My initial impulse was to maintain the confidentiality I’d promised, respecting the privacy that underpins the research relationship. However, the well-being of the participant superseded this initial priority. I recognized my ethical obligation to prioritize non-maleficence (avoiding harm) and beneficence (doing good).

I carefully weighed different options. I knew I couldn’t directly intervene as a therapist. Instead, I subtly directed the participant towards local mental health resources, offering support and highlighting the availability of help without pressuring disclosure. I documented the encounter in my field notes, ensuring the participant’s anonymity, but made a note indicating my concern without compromising their privacy. The rationale was to offer support and resources while respecting boundaries and prioritizing the participant’s autonomy.

Q 19. How do you ensure the ethical treatment of visual data collected in ethnographic studies?

Ethical treatment of visual data in ethnographic studies is critical. Researchers must ensure they have informed consent from all individuals captured in images or videos, specifically explaining how the images will be used and protected. This includes specifying whether they will be published, and if so, in what context. It’s also crucial to avoid misrepresenting individuals or cultures through selective editing or manipulation of images. Images should accurately reflect the reality of the situation and avoid perpetuating stereotypes or harmful representations.

Furthermore, researchers should be mindful of the power dynamics involved in visual representation. They should avoid exploiting participants through exploitative or intrusive photography and filming. Anonymity techniques should be employed whenever possible to protect individual privacy. In some cases, blurring faces or obscuring identifying features might be necessary to protect the anonymity of the participants. Respectful and ethical image capture practices are paramount. Open communication and collaboration with participants are key to ensuring their consent and avoiding any harm.

Q 20. How do you handle sensitive or controversial information gathered during research?

Handling sensitive or controversial information ethically requires careful consideration and planning. Researchers must prioritize confidentiality and anonymity, protecting the identity of participants and their communities. Data should be stored securely, with access restricted to authorized personnel only. Researchers should develop strategies for data anonymization to prevent identifying information from being revealed in publications or presentations.

If the research involves illegal activities, the ethical obligation shifts. Researchers might need to consider reporting requirements in accordance with legal and professional guidelines. There’s a need to balance the ethical obligation of confidentiality with any legal obligation of reporting unlawful activity. This should be carefully considered and guided by local laws and ethical review boards. A detailed ethical review protocol is usually required when dealing with particularly sensitive subject matter.

Q 21. What are the legal implications of violating ethical research guidelines?

Violating ethical research guidelines can have serious legal implications. Depending on the nature and severity of the violation, consequences can range from sanctions by professional organizations (such as revocation of research permits or funding) to legal action (such as lawsuits for breach of confidentiality or defamation). Researchers may face criminal charges if their actions violate laws, such as if research participants are harmed or if privacy rights are egregiously violated.

Institutions that sponsor research also face significant legal risk if their researchers engage in unethical practices. This includes potential lawsuits, damage to reputation, and loss of funding. Institutions usually have strict guidelines in place to ensure that their researchers adhere to ethical standards. Moreover, data protection laws such as GDPR (in Europe) and similar regulations impose legal obligations on researchers related to handling data. Non-compliance can result in severe penalties.

Q 22. What is the significance of debriefing participants after ethnographic research?

Debriefing is crucial in ethnographic research because it allows researchers to address any concerns participants might have after their involvement. It’s a chance for open dialogue, clarifying misunderstandings, and ensuring participants feel respected and empowered. Think of it as a post-study check-in, ensuring a smooth and ethical conclusion to the research process.

A thorough debriefing involves explaining the study’s findings (in a way that doesn’t compromise anonymity), offering an opportunity for participants to ask questions, and providing contact information for any future concerns. For example, if my research involved observing a community’s response to a new policy, the debrief would involve summarizing the observed trends, emphasizing that no individual was identified in the report, and offering a means for them to discuss their experiences or receive support if needed. This fosters trust and contributes to a positive research experience.

Q 23. How do you balance the goals of your research with the well-being of participants?

Balancing research goals with participant well-being is paramount in ethnography. It’s about ethical pragmatism – finding a middle ground where valuable data is collected without compromising the physical, emotional, or social welfare of those involved. This requires careful planning and a constant ethical reflexivity.

For example, if my research involves studying a vulnerable population, I would prioritize their safety and autonomy throughout the research process. This might mean adjusting my data collection methods, offering counseling resources, or prioritizing their comfort over maximizing data points. It’s about making informed decisions, prioritizing well-being, and adapting my methodology to ensure ethical conduct.

- Prioritize participant needs: Consider the potential risks involved and build safeguards into the study design.

- Transparency and informed consent: Clearly articulate the study’s purpose, procedures, and potential risks to participants.

- Data anonymization and confidentiality: Protect participants’ identity and privacy throughout the research process and dissemination of findings.

Q 24. Describe your familiarity with relevant ethical codes and guidelines (e.g., AAA, ASA).

I am intimately familiar with the ethical codes and guidelines of the American Anthropological Association (AAA) and the American Sociological Association (ASA), as well as relevant institutional review board (IRB) policies. These codes emphasize the importance of informed consent, confidentiality, anonymity, reciprocity, and minimizing harm to participants. The AAA’s Code of Ethics, for example, is a cornerstone for my practice, providing a framework for ethical decision-making in all stages of research, from planning to dissemination.

My understanding goes beyond simply knowing the guidelines; it informs my research design, data collection methods, and data analysis strategies. It guides how I approach issues of power dynamics in research relationships, ensuring that participants are treated with respect and their contributions are valued.

Q 25. How do you obtain and maintain informed consent in online or virtual ethnographic research?

Obtaining informed consent in online or virtual ethnographic research requires careful consideration of the digital environment. While the principles remain the same (transparency, autonomy, etc.), the methods need adaptation.

I would use secure online platforms to obtain consent, ensuring that the consent form is clear, accessible, and uses plain language. It must explicitly detail the research aims, methods, data usage, data security, participant rights (to withdraw, etc.), and any potential risks. The consent process would be digital, but it would prioritize clear communication, just as a face-to-face consent process would. I would also regularly check in with participants online to maintain contact and ensure ongoing consent.

For example, for online ethnographic research on a specific online community, I would design a consent form tailored to the digital context and obtain consent using a secure online platform. Regular check-ins through the platform would maintain open communication and address any emergent concerns. This approach helps me address the unique challenges of conducting research in the digital sphere while maintaining ethical standards.

Q 26. How would you address concerns raised by community members regarding your research?

Addressing concerns raised by community members is critical for maintaining trust and ensuring ethical research. It’s a two-way street; research is not just about extracting data but about building relationships and fostering understanding.

My approach would be to listen actively, validate their concerns, and engage in open dialogue. This might involve holding community meetings, adjusting the research design to address their concerns, or providing clear explanations of the research’s purpose and methodology. Transparency is key. For instance, if a community expresses concerns about data privacy, I would adjust my data anonymization protocols and clearly communicate these changes. If they felt the research was intrusive, I might modify my methods to reduce the impact on daily life. I’d make sure to work collaboratively to find solutions that address both their concerns and my research goals.

Q 27. What strategies do you employ for mitigating risks associated with participant observation?

Participant observation carries inherent risks, both for the researcher and the participants. Mitigating these risks requires proactive planning and careful consideration.

Strategies I employ include:

- Safety planning: This involves anticipating potential dangers, establishing clear communication protocols with colleagues or supervisors, and avoiding situations that could compromise my safety or the safety of participants.

- Informed consent and participant trust: Building trust with participants reduces the risk of misunderstanding or conflict.

- Reflexivity and self-awareness: Regularly reflecting on my role in the field helps identify and manage potential biases and power imbalances.

- Ethical boundaries: Maintaining professional boundaries is crucial to prevent exploitation or harm to participants.

- Data security: Ensuring the confidentiality and anonymity of participants’ data is vital.

Q 28. Explain your understanding of the ethical responsibilities of disseminating research findings.

Ethical dissemination of research findings means ensuring that the results are shared responsibly, respecting the rights and well-being of participants. This includes anonymizing data to protect identities, avoiding generalizations that could stigmatize particular groups, and presenting findings accurately and without bias.

Before publishing, I would carefully review my findings, ensuring that they are presented ethically. This includes considering the potential impact of my work on the communities studied. I would also engage in discussions with the community about the dissemination of my findings, ensuring they are informed and have the opportunity to provide feedback. The goal is to create knowledge that is both accurate and socially responsible, avoiding harm while fostering understanding and collaboration. The community’s feedback should be taken seriously, and if necessary, the research findings should be adapted accordingly.

Key Topics to Learn for Ethics in Ethnographic Research Interview

- Informed Consent: Understanding the principles of informed consent, including capacity, voluntariness, and comprehension. Practical application: Developing culturally sensitive consent procedures for diverse populations.

- Researcher Reflexivity: Recognizing and addressing your own biases and perspectives in the research process. Practical application: Developing strategies for self-reflection and mitigating potential biases in data collection and analysis.

- Data Anonymity and Confidentiality: Methods for protecting participant anonymity and confidentiality, including data security and storage protocols. Practical application: Applying appropriate anonymization techniques to qualitative data while maintaining the integrity of the research.

- Power Dynamics and Vulnerability: Addressing power imbalances between researcher and participants and mitigating potential risks to vulnerable populations. Practical application: Developing research protocols that prioritize participant well-being and safety.

- Ethical Dilemmas and Decision-Making: Identifying and navigating ethical challenges that may arise during fieldwork. Practical application: Applying ethical frameworks to resolve conflicts of interest or unforeseen circumstances.

- Institutional Review Boards (IRBs): Understanding the role of IRBs in reviewing and approving research proposals. Practical application: Preparing IRB applications that fully address ethical considerations.

- Cultural Sensitivity and Respect: Conducting research in a way that respects the cultural norms and values of the community being studied. Practical application: Engaging with community members respectfully and collaboratively throughout the research process.

- Responsible Data Sharing and Publication: Ethical considerations related to sharing and publishing research findings. Practical application: Ensuring appropriate attribution and protecting participant confidentiality in publications.

Next Steps

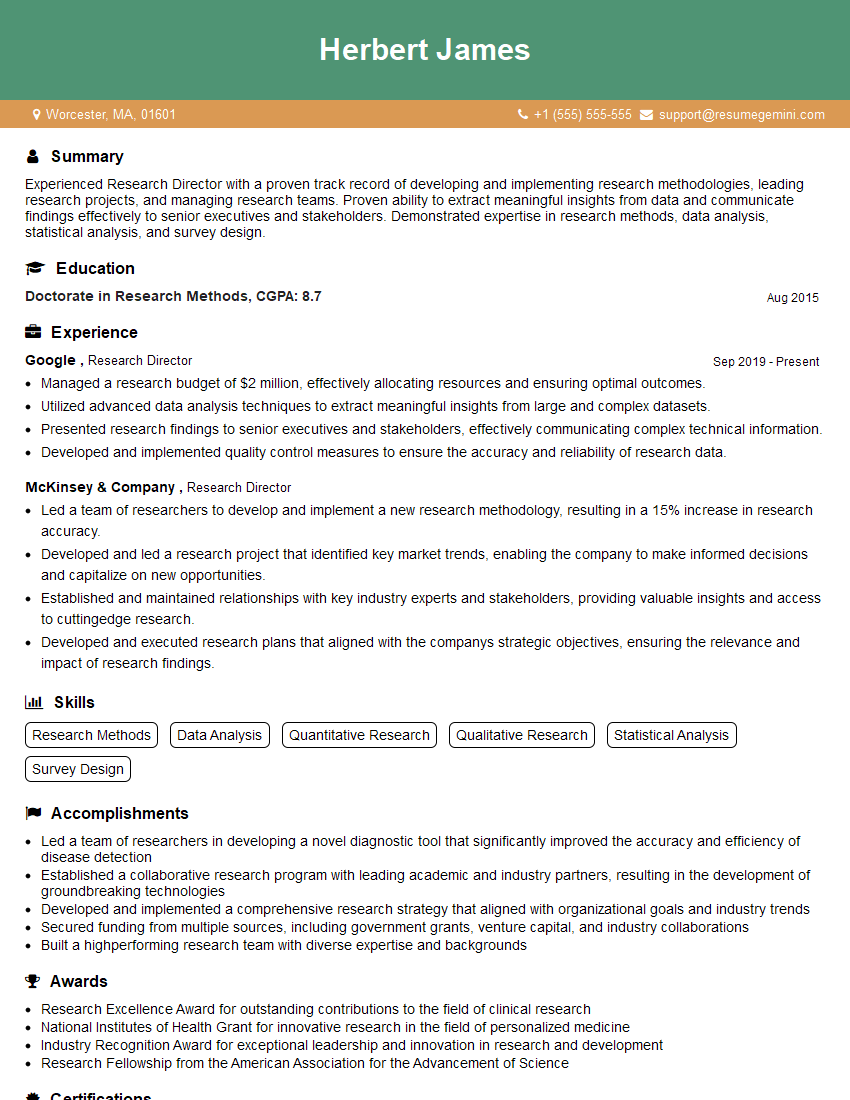

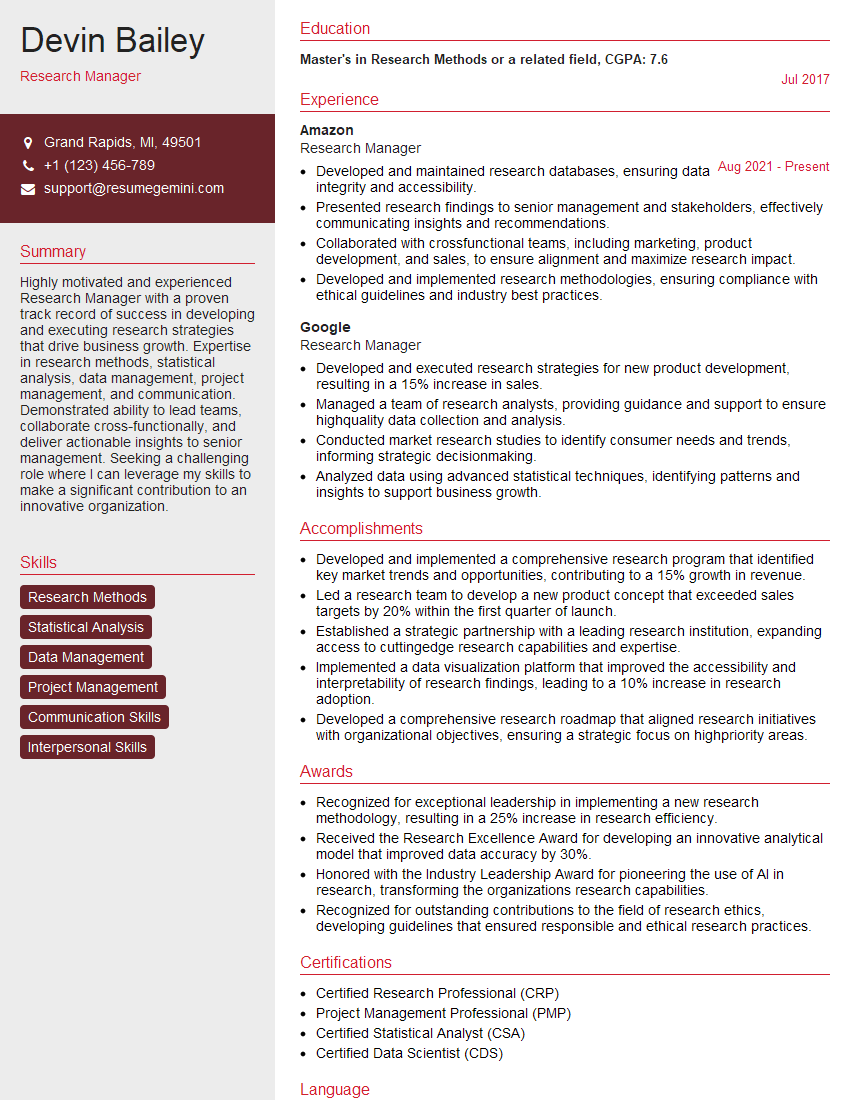

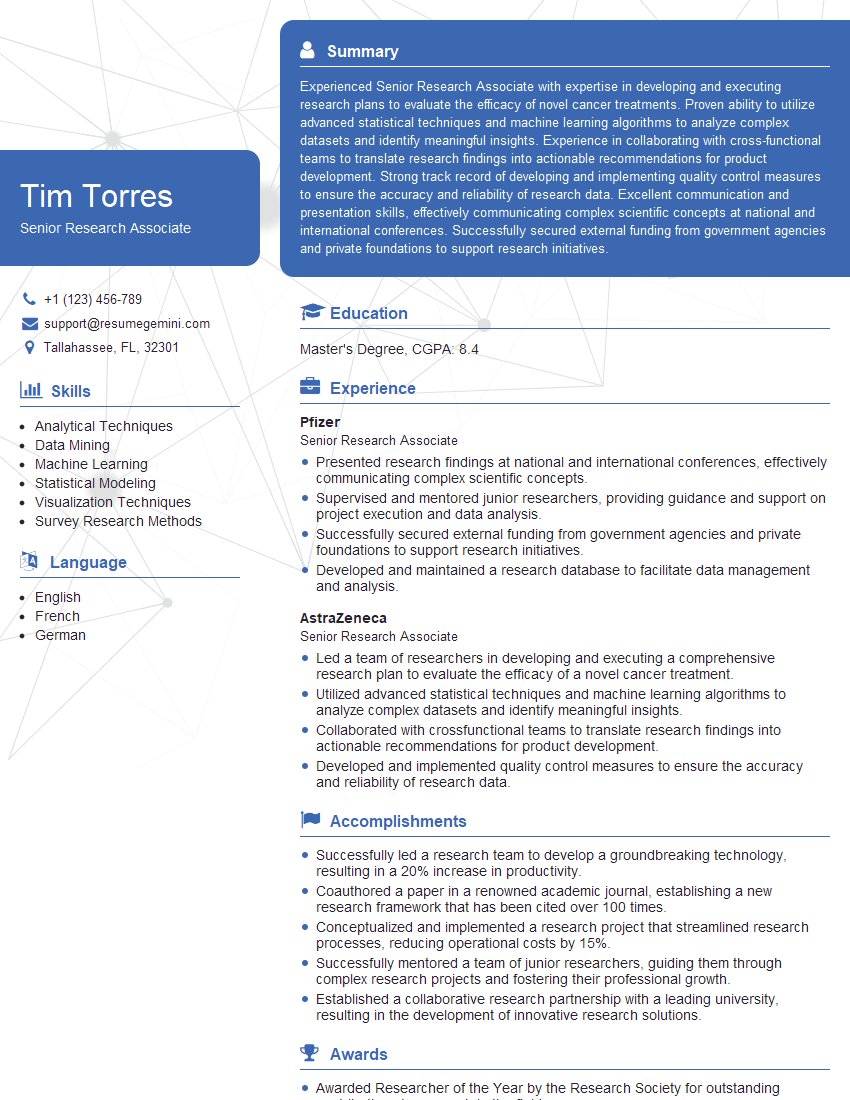

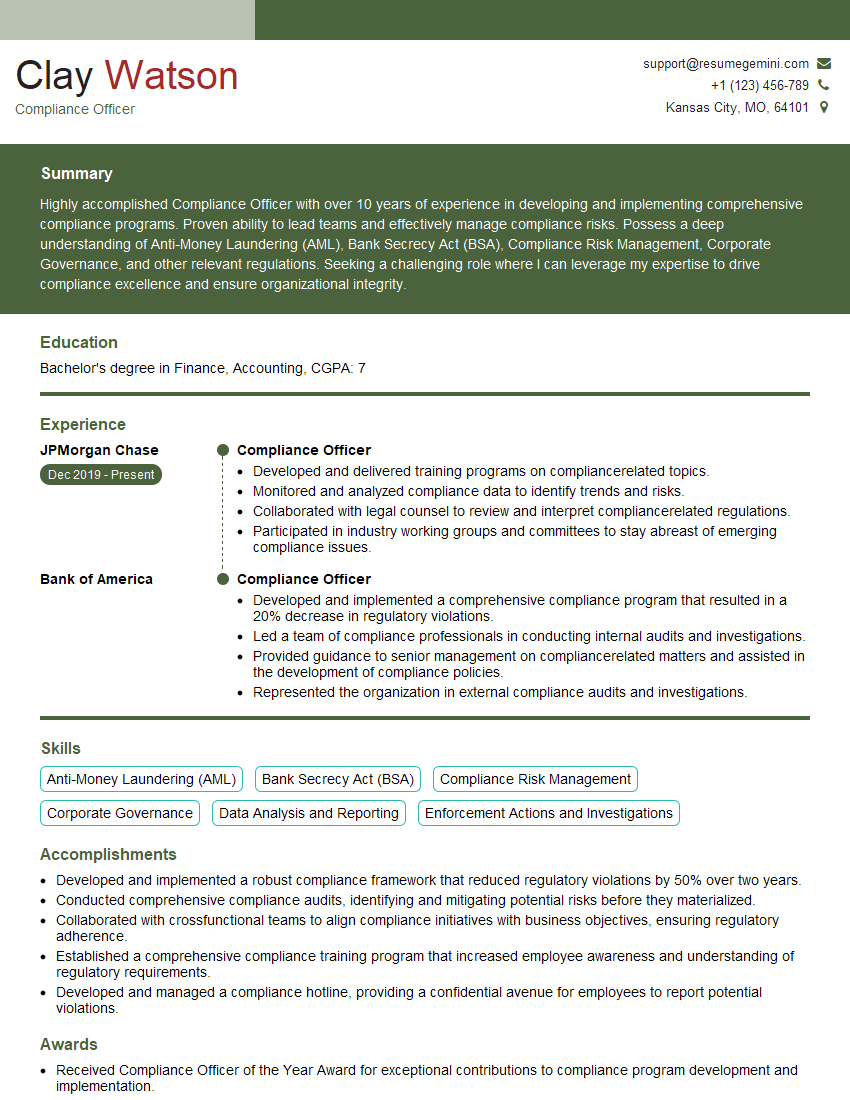

Mastering ethics in ethnographic research is crucial for building a successful career. A strong understanding of these principles demonstrates professionalism, integrity, and a commitment to responsible research practices, making you a highly desirable candidate. To further enhance your job prospects, creating an ATS-friendly resume is essential. ResumeGemini can help you build a compelling and effective resume that highlights your skills and experience in a way that Applicant Tracking Systems recognize. ResumeGemini provides examples of resumes tailored to Ethics in Ethnographic Research, allowing you to craft a document that showcases your expertise and sets you apart from the competition.

Explore more articles

Users Rating of Our Blogs

Share Your Experience

We value your feedback! Please rate our content and share your thoughts (optional).

What Readers Say About Our Blog

Hi, I have something for you and recorded a quick Loom video to show the kind of value I can bring to you.

Even if we don’t work together, I’m confident you’ll take away something valuable and learn a few new ideas.

Here’s the link: https://bit.ly/loom-video-daniel

Would love your thoughts after watching!

– Daniel

This was kind of a unique content I found around the specialized skills. Very helpful questions and good detailed answers.

Very Helpful blog, thank you Interviewgemini team.