The thought of an interview can be nerve-wracking, but the right preparation can make all the difference. Explore this comprehensive guide to Foot and Ankle Examination interview questions and gain the confidence you need to showcase your abilities and secure the role.

Questions Asked in Foot and Ankle Examination Interview

Q 1. Describe the proper technique for performing a thorough foot and ankle examination.

A thorough foot and ankle examination follows a systematic approach, ensuring no area is missed. It begins with a comprehensive patient history, focusing on the onset, location, and character of pain, any associated trauma, and past medical history. The physical exam itself proceeds in a logical order: inspection, palpation, range of motion assessment, neurological assessment, and special tests.

- Inspection: Observe the patient’s gait, looking for any limping or abnormalities. Examine the skin for lesions, discoloration, swelling, or deformities. Compare both feet for symmetry.

- Palpation: Systematically palpate bony landmarks, soft tissues, and tendons, noting any tenderness, swelling, warmth, or crepitus (a crackling sound).

- Range of Motion (ROM): Assess active and passive ROM in the ankle (dorsiflexion, plantarflexion, inversion, eversion) and subtalar joints. Compare ROM to the unaffected side.

- Neurological Exam: Evaluate sensation, strength, and reflexes in the foot and lower leg. This helps identify nerve involvement.

- Special Tests: Various tests are used based on the suspected pathology. For example, the Thompson test for Achilles tendon rupture, the anterior drawer test for ankle instability, or the squeeze test for stress fractures.

The entire process requires careful attention to detail, comparing findings to the unaffected side and noting any asymmetry. Thorough documentation is crucial, including observations, measurements (e.g., swelling), and the results of special tests.

Q 2. What are the key anatomical landmarks to palpate during a foot and ankle exam?

Palpating key anatomical landmarks is essential for a precise foot and ankle examination. These landmarks serve as reference points for identifying underlying pathology.

- Ankle: Medial and lateral malleoli (bony prominences on the inner and outer ankle), the distal ends of the tibia and fibula.

- Hindfoot: Calcaneus (heel bone), talus (the bone that sits on top of the heel bone and connects to the tibia).

- Midfoot: Navicular, cuboid, cuneiform bones (small bones forming the arch).

- Forefoot: Metatarsal heads (the bony prominences at the base of the toes), distal phalanges (tips of the toes).

- Tendons: Achilles tendon (at the back of the heel), tibialis anterior tendon (on the inner aspect of the ankle), peroneal tendons (on the outer aspect of the ankle).

- Nerves: Superficial peroneal nerve (outer aspect of the leg and foot), deep peroneal nerve (anterior aspect of the leg and foot), posterior tibial nerve (inner aspect of the leg and foot).

Palpation should be gentle yet thorough, comparing both sides to identify any discrepancies in tenderness, swelling, or temperature.

Q 3. How would you assess range of motion in the ankle and subtalar joints?

Assessing range of motion (ROM) in the ankle and subtalar joints requires a systematic approach and careful comparison to the contralateral (opposite) side. We assess both active and passive ROM.

- Ankle Joint ROM:

- Dorsiflexion: Moving the foot upward towards the shin.

- Plantarflexion: Pointing the foot downward.

- Subtalar Joint ROM: This refers to the movement between the talus and calcaneus (heel bone).

- Inversion: Turning the sole of the foot inward.

- Eversion: Turning the sole of the foot outward.

Passive ROM is assessed by the examiner moving the joint, while active ROM is assessed by asking the patient to move the joint themselves. Limitations in either can indicate injury or inflammation. For example, decreased dorsiflexion may indicate anterior impingement, while decreased plantarflexion may be seen in gastrocnemius tightness.

Q 4. Explain the difference between pes planus and pes cavus.

Pes planus and pes cavus are two opposite conditions describing the shape of the foot’s arch.

- Pes planus (flat foot): This refers to a collapsed medial longitudinal arch. The entire sole of the foot makes contact with the ground. It can be flexible (the arch appears when the patient is not weight-bearing) or rigid (the arch remains collapsed even when not weight-bearing). Causes can range from genetic predisposition to posterior tibial tendon dysfunction.

- Pes cavus (high arch): This is characterized by an excessively high medial longitudinal arch. The sole of the foot shows only limited contact with the ground. It can be associated with various neurological conditions, such as Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, or may be congenital. High arches can increase pressure on the forefoot, leading to metatarsalgia.

Differentiating between these conditions is visually straightforward but requires understanding the flexibility of the arch. A clinical assessment should always be performed, and imaging might be required to rule out more serious underlying causes.

Q 5. What are the common causes of plantar fasciitis?

Plantar fasciitis is a common cause of heel pain, characterized by inflammation of the plantar fascia, a thick band of tissue on the bottom of the foot.

- Overuse: Excessive weight-bearing activities, prolonged standing, or running without proper support are major contributing factors.

- Improper Footwear: Wearing shoes with inadequate arch support or excessively flat shoes can put undue stress on the plantar fascia.

- Obesity: Increased weight places greater strain on the plantar fascia.

- Muscle Imbalances: Tight calf muscles can increase tension on the plantar fascia.

- Biomechanical Factors: Foot pronation (inward rolling of the foot), high arches or flat feet can predispose individuals to plantar fasciitis.

- Other factors: Less commonly, certain autoimmune conditions, diabetes, or even genetics may play a role.

The interplay of these factors highlights the importance of considering a patient’s lifestyle, activity levels, footwear choices, and underlying conditions when diagnosing and treating plantar fasciitis.

Q 6. How would you differentiate between ankle sprain and fracture?

Differentiating between an ankle sprain and a fracture requires a careful clinical examination and often imaging studies. Both can present with significant pain and swelling.

- Ankle Sprain: This involves a stretching or tearing of one or more ligaments in the ankle. The pain is often localized to the affected ligament, and the ability to bear weight may be preserved, although it might be painful. Swelling and bruising are common.

- Ankle Fracture: This is a break in one or more of the bones in the ankle (tibia, fibula, or talus). The pain is typically more intense, and weight-bearing is often impossible. Significant swelling, bruising, and deformity (visual changes in the ankle’s shape) can be present. Crepitus may be palpable. Neurovascular compromise (decreased blood supply or nerve function) may occur.

Key Differences Summarized:

- Pain: Sprain – localized; Fracture – more intense and diffuse.

- Weight-bearing: Sprain – often possible, albeit painful; Fracture – usually impossible.

- Deformity: Sprain – usually absent; Fracture – can be present.

- Crepitus: Sprain – absent; Fracture – may be present.

- Neurovascular Compromise: Sprain – rare; Fracture – possible.

While a thorough clinical exam is essential, imaging, such as X-rays, is crucial for confirming a diagnosis of fracture and ruling out other injuries. The Ottawa Ankle Rules can help determine the need for imaging.

Q 7. Describe the clinical presentation of a patient with Achilles tendinitis.

Achilles tendinitis presents with pain and inflammation in the Achilles tendon, located at the back of the heel. The clinical presentation can vary in severity.

- Pain: The primary symptom is pain located in the back of the heel or slightly above, typically worsening with activity and improving with rest. The pain may radiate up the calf.

- Swelling: There might be mild to moderate swelling around the tendon. In severe cases, a palpable nodule (thickening) can be felt within the tendon.

- Stiffness: The patient may experience stiffness, especially in the morning or after periods of inactivity.

- Limited ROM: Active and passive plantarflexion may be limited due to pain.

- Crepitus: In some cases, a creaking or grating sensation (crepitus) may be felt or heard when the tendon is palpated.

Patients might describe their pain as a dull ache or a sharp, stabbing pain. The diagnosis is typically made based on the patient’s history, physical examination findings, and imaging studies like ultrasound, if necessary. Treatment focuses on rest, ice, compression, elevation (RICE), and physical therapy to improve flexibility and strength.

Q 8. What are the potential complications of a diabetic foot ulcer?

Diabetic foot ulcers, seemingly simple wounds, pose a significant threat due to the underlying neuropathy (nerve damage) and impaired blood circulation common in diabetes. These complications can range from relatively minor infections to life-altering consequences.

- Infection: The most common complication. Ulcers provide an entry point for bacteria, leading to cellulitis (skin infection), osteomyelitis (bone infection), and even sepsis (a life-threatening bloodstream infection). Poor blood supply hinders the body’s ability to fight off infection effectively.

- Gangrene: Severe infection and compromised blood flow can lead to tissue death (gangrene). This necessitates amputation to prevent the spread of infection.

- Amputation: In advanced cases, amputation of the affected toe, foot, or even leg may be the only way to save the patient’s life. This highlights the crucial importance of early diagnosis and treatment.

- Chronic Wound Healing: Diabetic patients often experience delayed wound healing, making ulcers prone to lingering for extended periods. This increases the risk of infection and other complications.

- Pain: While neuropathy may mask pain, the underlying infection can still cause significant pain. This can impact mobility and overall quality of life.

Imagine a patient with diabetes who develops a small ulcer on their foot. Initially, they might not notice it due to neuropathy. However, if left untreated, this seemingly insignificant wound could quickly escalate to a serious infection requiring extensive treatment, possibly including amputation. This underscores the importance of regular foot checks and prompt medical attention for any foot problem in diabetic patients.

Q 9. Explain the Ottawa Ankle Rules and their significance.

The Ottawa Ankle Rules are a clinical decision rule used to determine whether or not an ankle or foot X-ray is necessary following a suspected ankle injury. Their significance lies in their ability to reduce unnecessary X-rays, saving time, money, and radiation exposure for patients. The rules are based on clinical findings that are highly sensitive in identifying ankle fractures requiring imaging.

The rules state that an ankle X-ray is indicated if any of the following are present:

- Bone tenderness at the posterior edge or tip of the lateral malleolus (outer ankle bone).

- Bone tenderness at the posterior edge or tip of the medial malleolus (inner ankle bone).

- Inability to bear weight both immediately and in the emergency department (unable to take four steps).

For the foot, an X-ray is indicated if there is bone tenderness at the base of the fifth metatarsal (little toe side) or navicular bone (arch).

Significance: The rules are highly sensitive, meaning that they rarely miss a fracture that requires treatment. By reducing unnecessary X-rays, they save healthcare resources and reduce patient exposure to radiation. They are widely adopted in emergency departments and are a cornerstone of efficient and responsible ankle injury management.

Q 10. How would you assess for neurological deficits in the foot and ankle?

Assessing for neurological deficits in the foot and ankle involves a systematic examination focusing on sensory, motor, and reflex functions. This helps identify any nerve damage that could be contributing to symptoms or predisposing the patient to further injury.

- Sensory Examination: This assesses the patient’s ability to feel light touch, pinprick, temperature, and vibration. A monofilament test, using a fine nylon filament, is used to assess protective sensation – crucial for identifying at-risk individuals. This might reveal areas of numbness or decreased sensation.

- Motor Examination: This evaluates muscle strength and range of motion in the foot and ankle. We assess the strength of key muscles such as the tibialis anterior (dorsiflexion), gastrocnemius and soleus (plantarflexion), and others to detect weakness suggesting nerve damage.

- Reflex Examination: Testing deep tendon reflexes, such as the Achilles reflex, helps to evaluate the integrity of the nerve pathways. Diminished or absent reflexes can indicate nerve damage.

For instance, a patient with diabetes might present with reduced sensation in the plantar aspect of their foot (sole) due to peripheral neuropathy. This would put them at high risk for developing foot ulcers, as they might not feel minor injuries. The comprehensive neurological examination is fundamental in identifying such vulnerabilities.

Q 11. What imaging modalities would you consider for evaluating a foot and ankle injury?

The choice of imaging modality for a foot and ankle injury depends on the suspected injury and clinical findings. Several options are available, each offering unique advantages:

- X-ray: The initial imaging modality of choice for most ankle and foot injuries. It effectively visualizes bones and can detect fractures, dislocations, and arthritis. It’s readily available, relatively inexpensive, and involves low radiation exposure.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: Provides detailed cross-sectional images of the bones, allowing for better visualization of complex fractures and subtle bone abnormalities that might be missed on an X-ray. It’s particularly helpful in assessing the extent of injuries involving multiple bones.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Offers excellent visualization of soft tissues, including ligaments, tendons, muscles, cartilage, and nerves. It’s useful for diagnosing sprains, tears, and other soft tissue injuries that might not be apparent on X-rays or CT scans.

- Ultrasound: Provides real-time images of soft tissues. It’s useful for assessing tendon injuries, fluid collections, and nerve entrapments. It’s non-invasive and relatively inexpensive.

For example, a patient presenting with severe ankle pain and swelling after an inversion injury might undergo an X-ray initially. If the X-ray reveals a complex fracture or if there’s suspicion of ligamentous injury, an MRI might be indicated to fully assess the extent of the damage.

Q 12. Describe the different types of ankle fractures.

Ankle fractures are broadly classified based on the bones involved and the type of fracture. The most commonly fractured bones are the malleoli (lateral and medial), and the posterior malleolus.

- Unimalleolar fractures: Involve only one malleolus (either lateral or medial).

- Bimalleolar fractures: Involve both the lateral and medial malleoli.

- Trimalleolar fractures: Involve the lateral and medial malleoli, as well as the posterior malleolus.

- Pilon fractures: These are severe fractures involving the distal tibia and fibula, often extending into the articular surface of the ankle joint. They are usually highly comminuted (shattered) and often require complex surgical intervention.

- Supramalleolar fractures: These fractures occur above the ankle joint, affecting the tibia or fibula.

The classification is important because it guides treatment decisions. A simple unimalleolar fracture might be treated non-operatively (with casting), while a complex pilon fracture would almost certainly require surgery.

Q 13. What are the surgical options for a severe ankle injury?

Surgical options for severe ankle injuries depend on the specific injury and the patient’s overall health. The goals of surgery are to restore anatomical alignment, stabilize the fracture, and promote healing.

- Open Reduction and Internal Fixation (ORIF): This involves surgically exposing the fracture site, realigning the bones (reduction), and then securing them in place with screws, plates, or other implants (internal fixation). This is commonly used for displaced fractures, particularly those involving the articular surface.

- External Fixation: This involves applying a metal frame externally to the leg, with pins inserted into the bone fragments. It provides stable fixation and allows for early mobilization, but it’s less cosmetically appealing than ORIF.

- Arthrodesis (Ankle Fusion): This involves surgically fusing the ankle joint, effectively eliminating movement. It’s usually reserved for severe cases where joint preservation is not possible, often due to extensive arthritis or damage.

The choice of surgery depends on many factors, including the type and severity of the fracture, the patient’s age, activity level, and overall health. A young, active patient with a displaced bimalleolar fracture is likely to undergo ORIF to maximize the chances of restoring normal ankle function. In contrast, an elderly patient with severe arthritis and a comminuted pilon fracture might be better suited for an ankle fusion.

Q 14. What is the role of physical therapy in the rehabilitation of foot and ankle injuries?

Physical therapy plays a vital role in the rehabilitation of foot and ankle injuries, aiming to restore function, reduce pain, and prevent long-term complications. The specific program is tailored to the individual’s needs and injury type, but generally includes:

- Range of Motion Exercises: Gentle exercises to improve ankle and foot mobility, gradually increasing the range and intensity as tolerated. This helps prevent stiffness and contractures.

- Strengthening Exercises: Targeted exercises to strengthen the muscles surrounding the ankle and foot, improving stability and support.

- Proprioceptive Exercises: These exercises challenge balance and coordination to improve neuromuscular control, reducing the risk of re-injury. This might involve standing on uneven surfaces.

- Functional Exercises: Activities that simulate everyday movements, such as walking, stair climbing, and jumping. This prepares the patient for a return to normal activities.

- Modalities: Use of therapeutic modalities such as ice, heat, ultrasound, or electrical stimulation to manage pain and inflammation.

- Manual Therapy: Hands-on techniques to improve joint mobility and soft tissue mobility.

For example, a patient recovering from an ankle sprain might begin with range of motion exercises and ice, gradually progressing to strengthening exercises, proprioceptive training, and functional activities like walking on a treadmill. The duration and intensity of physical therapy depend on the severity of the injury and the patient’s response to treatment. Early and diligent participation in physical therapy is crucial for optimal recovery and return to function.

Q 15. How would you manage a patient with hallux valgus?

Managing hallux valgus, commonly known as a bunion, involves a multi-faceted approach tailored to the patient’s specific symptoms and the severity of the deformity. Initially, conservative management is often attempted. This includes:

- Orthotic devices: Custom or over-the-counter inserts can help redistribute pressure and alleviate pain.

- Proper footwear: Patients are advised to wear wider, roomy shoes with a low heel to avoid further stressing the joint. Avoid high heels and pointed-toe shoes.

- Pain management: This may involve over-the-counter NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) like ibuprofen, or in some cases, prescription pain medication.

- Padding: Protective pads can cushion the bunion and reduce friction and pressure.

If conservative measures fail to provide adequate relief, surgical intervention may be considered. Surgical options vary depending on the severity of the deformity and include procedures such as osteotomy (re-shaping of the bone), arthrodesis (fusion of the joint), or soft tissue procedures to correct the alignment. Post-surgical care involves a period of immobilization, physical therapy, and gradual return to activity.

For example, a patient with mild hallux valgus and manageable pain might benefit from orthotics and shoe modifications. However, a patient with severe pain and significant deformity would likely be a candidate for surgery. The decision always involves a thorough discussion with the patient about the benefits, risks, and potential outcomes of each treatment option.

Career Expert Tips:

- Ace those interviews! Prepare effectively by reviewing the Top 50 Most Common Interview Questions on ResumeGemini.

- Navigate your job search with confidence! Explore a wide range of Career Tips on ResumeGemini. Learn about common challenges and recommendations to overcome them.

- Craft the perfect resume! Master the Art of Resume Writing with ResumeGemini’s guide. Showcase your unique qualifications and achievements effectively.

- Don’t miss out on holiday savings! Build your dream resume with ResumeGemini’s ATS optimized templates.

Q 16. Describe the different types of bunions and their treatments.

Bunions aren’t all the same. We classify them based on several factors, including their location and severity. While the term ‘bunion’ often refers to hallux valgus (a bony prominence at the base of the big toe), other bunions exist:

- Hallux Valgus: The most common type, characterized by a lateral deviation of the big toe, often causing a prominent bump.

- Tailor’s Bunion (Bunionette): This is a bunion that develops at the base of the little toe (fifth metatarsophalangeal joint).

- Sesamoiditis: While not strictly a bunion, it involves inflammation of the sesamoid bones under the big toe, causing pain and sometimes a prominence similar to a bunion.

Treatments vary depending on the type and severity of the bunion. For all types, conservative management (as described in the previous answer) is usually the first line of treatment. Surgical correction might be necessary for severe cases causing significant pain or functional limitations. Surgical techniques are specifically chosen based on the type of bunion and the individual patient’s anatomy and needs. For example, a bunionectomy is a common procedure for hallux valgus.

Q 17. What are the common causes of heel pain?

Heel pain is a common complaint with multiple potential causes. Some of the most frequent culprits include:

- Plantar fasciitis: Inflammation of the plantar fascia, a thick band of tissue on the bottom of the foot, is a leading cause of heel pain. This often causes sharp pain in the heel, particularly in the morning or after periods of rest.

- Heel spurs: These are bony growths that develop on the heel bone (calcaneus). They often occur in conjunction with plantar fasciitis but can also be asymptomatic.

- Achilles tendinitis: Inflammation of the Achilles tendon, connecting the calf muscles to the heel bone, causes pain in the back of the heel.

- Stress fractures: Overuse injuries causing tiny cracks in the heel bone are a possibility, especially in athletes.

- Sever’s disease: This is a condition affecting children during growth spurts, causing inflammation of the heel bone’s growth plate.

- Fat pad atrophy: Thinning of the fatty tissue cushioning the heel can result in increased pressure and pain.

A thorough physical examination, including palpation of the heel and assessment of range of motion, is crucial for diagnosing the specific cause of heel pain.

Q 18. Explain the biomechanics of gait and how it relates to foot and ankle disorders.

Gait analysis, the study of how we walk, is fundamental to understanding foot and ankle disorders. Normal gait involves a complex interplay of muscle actions, joint movements, and skeletal alignment. It’s a cyclical pattern with distinct phases: stance and swing. Any deviation from this normal pattern can significantly contribute to foot and ankle problems.

Biomechanics of Gait: The gait cycle begins with heel strike, followed by foot flat, midstance, heel-off, and toe-off. During this cycle, the foot acts as a rigid lever during push-off and a flexible adaptor during initial contact, absorbing impact. Improper foot function can lead to abnormal stresses on joints higher up the kinetic chain.

Relationship to Foot and Ankle Disorders: Abnormal gait patterns are often implicated in the development of numerous disorders: overpronation (excessive inward rolling of the foot) can contribute to plantar fasciitis, bunions, and knee pain. Supination (outward rolling) can lead to ankle sprains and stress fractures. Other issues like decreased ankle dorsiflexion or limited hip range of motion can alter gait mechanics and increase the risk of injury. Gait analysis helps identify these biomechanical abnormalities and guide treatment strategies, such as orthotics or physical therapy, to improve gait and reduce the risk of further problems. For example, a patient presenting with chronic lateral ankle pain might have a gait pattern revealing excessive supination that can be addressed with custom orthotics to help support the arch.

Q 19. How would you assess for Morton’s neuroma?

Morton’s neuroma is a benign condition affecting the nerves between the toes, typically the third and fourth metatarsals. Assessing for it involves a combination of history and physical examination:

- History: Patients often report a burning, tingling, or numbness between the affected toes, often described as a ‘pebble in the shoe’ sensation. The pain often worsens with activity and is relieved by rest or removing shoes.

- Physical Examination: The Mulder’s click test is a key diagnostic maneuver. The examiner palpates the plantar aspect of the foot between the metatarsal heads and gently squeezes the metatarsals. A palpable click or a snapping sensation suggests a positive test indicative of Morton’s neuroma.

- Imaging: While not always necessary, imaging such as ultrasound or MRI may be used to confirm the diagnosis and rule out other conditions.

It’s important to differentiate Morton’s neuroma from other conditions with similar symptoms, such as metatarsalgia or stress fractures. A thorough history, focused physical exam, and when needed, appropriate imaging studies are crucial for accurate diagnosis.

Q 20. What are the common causes of foot and ankle infections?

Foot and ankle infections can stem from various sources:

- Open wounds: Cuts, abrasions, punctures, and surgical wounds provide entry points for bacteria.

- Ingrown toenails: Inflammation of the surrounding tissue can create a site for infection.

- Diabetic foot ulcers: Patients with diabetes have impaired wound healing and are at significantly increased risk of infection.

- Skin conditions: Conditions like athlete’s foot or eczema can weaken the skin’s barrier, making it susceptible to infections.

- Hematogenous spread: Bacteria can spread through the bloodstream from a distant infection to the foot or ankle.

Common causative organisms include Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus species, and anaerobic bacteria. The risk factors for infection include diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, immunosuppression, and poor hygiene.

Q 21. How would you manage a patient with a foot and ankle infection?

Managing a foot and ankle infection requires a prompt and appropriate response. The approach is guided by the severity and location of the infection. Treatment may include:

- Wound care: Cleaning the wound, removing debris and necrotic tissue (dead tissue), and appropriate dressings are essential to prevent further spread.

- Antibiotics: Systemic antibiotics are crucial, with the choice guided by culture and sensitivity testing. The duration of antibiotic therapy depends on the severity of the infection and the patient’s response.

- Debridement: Surgical removal of infected tissue might be necessary for severe infections or those failing to respond to conservative management. This may involve surgical removal of necrotic tissue or even amputation in extreme cases.

- Pain management: Analgesics such as acetaminophen or NSAIDs can be utilized to help manage pain.

- Elevation and immobilization: Reducing weight bearing and elevation can aid healing and reduce pain and swelling.

Monitoring for signs of worsening infection such as increased pain, swelling, redness, or fever is crucial. In cases of severe or rapidly progressing infections, urgent medical intervention is necessary to prevent serious complications, such as sepsis or osteomyelitis (bone infection). Regular monitoring is vital to ensure effective healing.

Q 22. Describe the signs and symptoms of compartment syndrome in the leg.

Compartment syndrome is a serious condition where increased pressure within a muscle compartment of the leg compromises blood supply to the muscles and nerves within. Think of it like a swollen sausage bursting its casing.

Signs and Symptoms: These often appear suddenly, especially after a traumatic injury like a fracture or crush injury, but can also develop gradually.

- Pain: Intense, disproportionate pain, often out of proportion to the apparent injury. This pain is worsened with passive stretching of the affected muscles.

- Paresthesia: Numbness or tingling in the affected compartment.

- Pallor: Pale skin color in the affected area due to reduced blood flow.

- Paralysis: Weakness or loss of function in the affected muscles. This is a late sign and indicates severe compromise.

- Pulselessness: Diminished or absent pulses in the affected extremity. This is also a late and serious sign.

Important Note: Compartment syndrome is a surgical emergency requiring immediate fasciotomy (surgical incision) to relieve the pressure. Delay in treatment can lead to permanent muscle damage, nerve damage, and even limb loss.

Q 23. What are the different types of ankle sprains and their management?

Ankle sprains are injuries to the ligaments that support the ankle joint. They are graded based on the severity of the ligament damage.

- Grade I (Mild): Stretching of the ligaments with minimal tearing. Often presents with mild pain, swelling, and minimal instability.

- Grade II (Moderate): Partial tearing of the ligaments. Characterized by moderate pain, swelling, and some instability.

- Grade III (Severe): Complete rupture of the ligaments. Severe pain, swelling, instability, and often significant bruising are present.

Most common type: Lateral ankle sprains (involving the anterior talofibular ligament) are the most frequent, often occurring during inversion injuries (rolling the ankle inwards).

Management: Treatment depends on the severity.

- Grade I: RICE (Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation), analgesics (pain relievers), and early mobilization.

- Grade II: RICE, analgesics, possibly a walking boot or air cast for support and protection, and physiotherapy to regain range of motion and strength.

- Grade III: May require surgical repair, especially if significant instability persists. Post-operative care will include immobilization, physiotherapy, and gradual weight-bearing.

Example: A basketball player who inverts their ankle during a game may experience a Grade II lateral ankle sprain, requiring a few weeks of immobilization and physiotherapy to recover fully.

Q 24. Explain the role of orthotics in the treatment of foot and ankle disorders.

Orthotics are custom-made or prefabricated devices designed to support and correct foot and ankle alignment. They act like a custom-built foundation for the foot, improving biomechanics and reducing stress on the joints.

Role in Treatment:

- Correcting biomechanical abnormalities: Orthotics can address issues like overpronation (excessive inward rolling of the foot), supination (excessive outward rolling), and foot arch deformities (flat feet, high arches).

- Reducing pain and inflammation: By improving biomechanics, they reduce stress on painful joints, tendons, and ligaments.

- Improving function: Orthotics can improve gait (walking pattern), balance, and overall foot and ankle function.

- Preventing further injury: They can help prevent recurring injuries by supporting the foot and ankle in a more stable and balanced position.

Example: A patient with plantar fasciitis (pain in the heel and arch) might benefit from orthotics to support the arch, reduce strain on the plantar fascia, and alleviate pain.

Q 25. What are the contraindications for specific foot and ankle surgical procedures?

Contraindications for foot and ankle surgery vary depending on the specific procedure, but some general contraindications include:

- Active infection: Surgery should be postponed until the infection is cleared to avoid spreading the infection.

- Poor vascular supply: Inadequate blood flow to the surgical site can compromise healing and increase the risk of complications. This is particularly important in procedures involving bone healing.

- Uncontrolled medical conditions: Conditions like diabetes, heart disease, or lung disease can significantly increase surgical risks and should be optimally managed before surgery.

- Patient non-compliance: Surgery may be contraindicated if the patient is unwilling or unable to follow post-operative instructions, which is crucial for successful recovery.

- Severe peripheral neuropathy: In patients with significant nerve damage, the ability to assess post-operative pain and function is impaired, raising concerns about complication identification.

Specific examples: A patient with a severe infection in their foot would need antibiotic treatment before considering any surgical procedure. Similarly, a patient with poorly controlled diabetes might require optimization of their blood sugar levels before undergoing ankle fusion surgery.

Q 26. How would you counsel a patient regarding post-operative care following foot and ankle surgery?

Post-operative care instructions are vital for successful recovery and should be tailored to the specific surgery performed. It’s like giving a detailed instruction manual for your newly repaired machine. The following are general guidelines:

- Pain management: Patients are educated about appropriate pain management strategies, including prescribed medication and ice application.

- Wound care: Detailed instructions on keeping the incision clean and dry, recognizing signs of infection, and changing dressings as needed are provided.

- Immobilization and weight-bearing: Patients are instructed on the use of casts, splints, or other immobilization devices and when and how they can gradually resume weight-bearing activities.

- Physical therapy: The importance of attending physical therapy sessions to regain range of motion, strength, and function is emphasized.

- Follow-up appointments: Scheduling and attending regular follow-up appointments are critical for monitoring healing progress and addressing any complications.

- Activity modification: Patients are advised on modifications to their daily activities to avoid re-injury and to allow for proper healing.

Example: After an ankle fracture repair, I would explain the importance of keeping the leg elevated to reduce swelling, using crutches for weight bearing restrictions, and the need for regular physical therapy to restore mobility.

Q 27. Describe your experience with different types of diagnostic nerve blocks.

Diagnostic nerve blocks involve injecting local anesthetic near specific nerves to temporarily numb the area and help diagnose the source of pain. They provide a temporary “test run” to see if a specific nerve is the problem.

Types of Nerve Blocks I’ve Used:

- Ankle joint blocks: These are performed by injecting anesthetic around the ankle joint to diagnose arthritis, ligament injuries, or other sources of ankle pain. This helps differentiate from soft tissue pain.

- Posterior tibial nerve blocks: This targets the posterior tibial nerve, which runs along the inside of the ankle and foot. It’s useful for diagnosing conditions affecting the heel, arch, and plantar fascia.

- Sural nerve blocks: This block numbs the outer side of the ankle and foot, helping diagnose conditions involving the lateral ankle or outer foot.

- Medial plantar nerve blocks: Used to diagnose plantar pain.

Experience: I have extensive experience performing and interpreting results from these blocks. Accurate injection technique and careful patient history are essential for reliable results. A successful block relieves the patient’s pain, providing strong evidence that the targeted nerve is the source of the problem. The opposite is also true. Failure to relieve pain indicates another source of the problem.

Q 28. How do you approach patients with complex foot and ankle pathology?

Managing patients with complex foot and ankle pathology requires a systematic approach that combines a detailed history, thorough physical examination, advanced imaging techniques, and careful consideration of surgical and non-surgical treatment options.

My Approach:

- Comprehensive history: Gleaning detailed information about the onset, duration, character, and progression of symptoms is essential.

- Thorough physical examination: A detailed musculoskeletal exam, neurological exam, and vascular assessment to define the limitations and contributing factors to their condition.

- Advanced imaging: Utilizing X-rays, CT scans, MRI scans and sometimes bone scans to gain a clear understanding of the underlying anatomy and pathology.

- Conservative management: Exploring non-surgical options such as orthotics, physical therapy, medications, and injections to determine efficacy before resorting to surgery.

- Surgical planning: If surgery is indicated, developing a detailed surgical plan that addresses the specific pathology and considers patient factors is paramount. This includes careful pre-operative planning and a thoughtful discussion of potential risks and benefits.

- Multidisciplinary approach: Consulting with other specialists as needed, such as podiatrists, physiatrists, or other surgeons, to leverage a wide range of expertise.

- Long-term management: Following the patient’s recovery progress through regular follow-up visits and providing appropriate recommendations for rehabilitation and preventative care.

Example: A patient with Charcot neuroarthropathy (a destructive foot condition) would require careful management involving regular monitoring, bracing, and possibly multiple surgical interventions over time. This needs a detailed understanding of their underlying neuropathy and vascular status.

Key Topics to Learn for Foot and Ankle Examination Interview

- Patient History Taking: Understanding the importance of a thorough patient history, including chief complaint, mechanism of injury, past medical history, and relevant social history. Practical application: Differentiating between various presentations of ankle sprains based on patient history alone.

- Inspection and Palpation: Mastering visual assessment of the foot and ankle for deformities, swelling, bruising, and skin changes. Practical application: Identifying potential fractures or ligamentous injuries through careful palpation and observation.

- Range of Motion (ROM) Assessment: Understanding normal and abnormal ROM in the ankle and foot joints. Practical application: Accurately measuring and documenting ROM to assess the extent of injury or limitation.

- Special Tests: Knowing the indications and proper techniques for performing various special tests (e.g., anterior drawer test, talar tilt test, Thompson test). Practical application: Interpreting the results of special tests to arrive at a differential diagnosis.

- Neurovascular Assessment: Assessing for sensory deficits, motor weakness, and circulatory compromise. Practical application: Recognizing and managing potential complications like nerve injury or compartment syndrome.

- Gait Analysis: Observing and interpreting gait patterns to identify underlying biomechanical issues. Practical application: Identifying compensatory movements that may indicate a specific injury or condition.

- Imaging Interpretation (Basic): Familiarity with common imaging modalities (X-ray, MRI, CT) and their use in diagnosing foot and ankle pathology. Practical application: Understanding the limitations and strengths of different imaging techniques.

- Differential Diagnosis: Developing the ability to differentiate between various foot and ankle conditions based on clinical findings. Practical application: Formulating a comprehensive and accurate differential diagnosis based on all collected data.

Next Steps

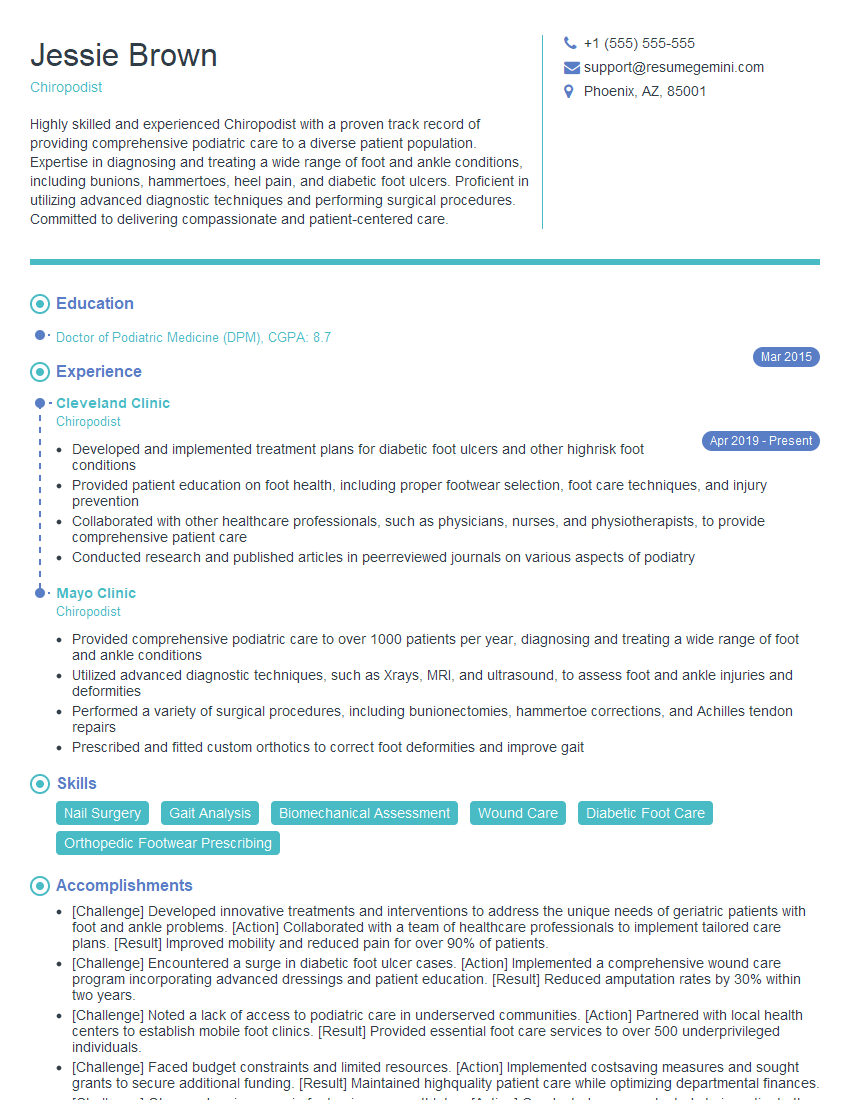

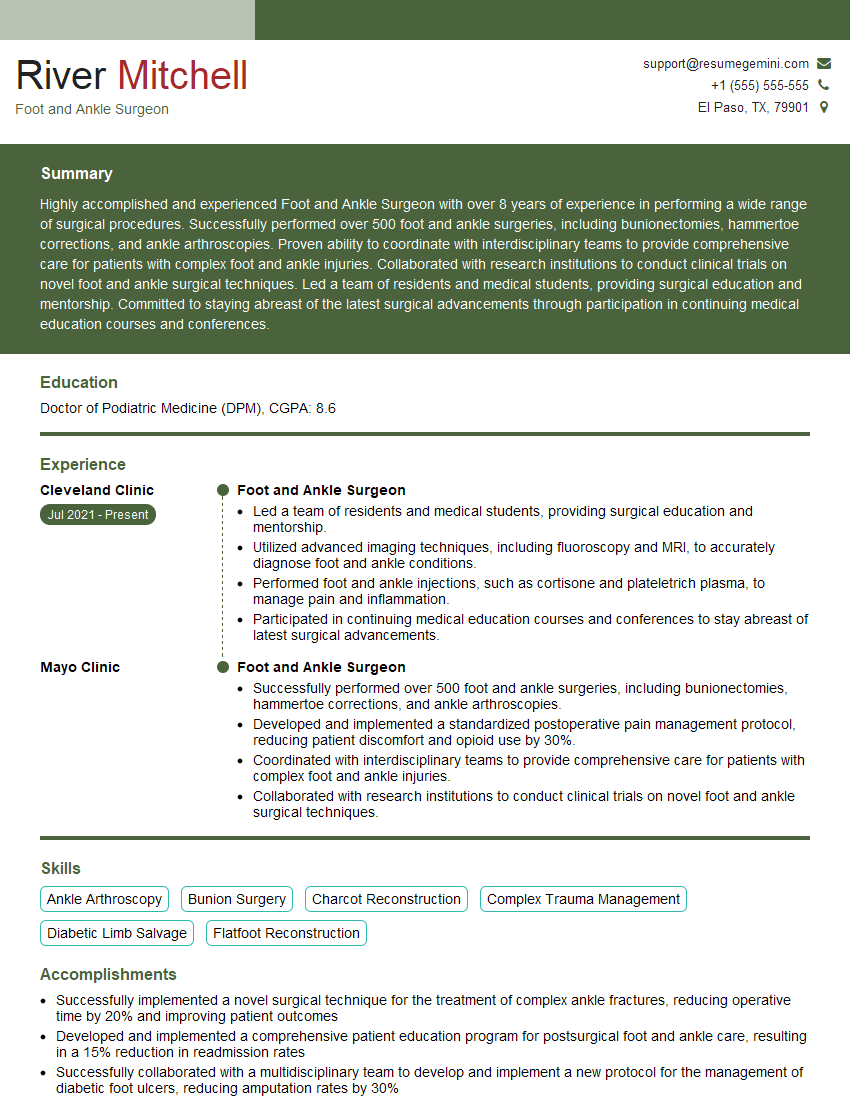

Mastering the foot and ankle examination is crucial for a successful career in this specialized field. A strong understanding of these techniques will significantly enhance your diagnostic skills and patient care abilities. To further boost your job prospects, create an ATS-friendly resume that highlights your skills and experience effectively. ResumeGemini is a trusted resource to help you build a professional and impactful resume. Examples of resumes tailored to Foot and Ankle Examination are available to help guide you. Invest in your career—invest in your resume.

Explore more articles

Users Rating of Our Blogs

Share Your Experience

We value your feedback! Please rate our content and share your thoughts (optional).

What Readers Say About Our Blog

This was kind of a unique content I found around the specialized skills. Very helpful questions and good detailed answers.

Very Helpful blog, thank you Interviewgemini team.