Every successful interview starts with knowing what to expect. In this blog, we’ll take you through the top Music History and Analysis interview questions, breaking them down with expert tips to help you deliver impactful answers. Step into your next interview fully prepared and ready to succeed.

Questions Asked in Music History and Analysis Interview

Q 1. Compare and contrast the musical styles of the Baroque and Classical periods.

The Baroque (roughly 1600-1750) and Classical (roughly 1730-1820) periods represent distinct yet connected stages in Western music history. While both eras emphasized formal structure, their approaches differed significantly.

- Baroque: Characterized by elaborate ornamentation, complex counterpoint (multiple independent melodic lines woven together), basso continuo (a continuous bass line supporting the harmony), terraced dynamics (sudden shifts in volume), and the use of ornamentation. Think of the grandeur and drama of Bach’s fugues or the passionate intensity of Vivaldi’s concertos. The overall aesthetic is often described as ornate, dramatic, and emotionally intense.

- Classical: Emphasized clarity, balance, and elegance. Composers favored homophonic texture (a melody supported by chords), simpler counterpoint, clearer melodic lines, and a wider dynamic range with smoother transitions. Forms like the sonata-allegro and string quartet became central. Think of the graceful melodies of Mozart or the structural perfection of Haydn’s symphonies. The overall aesthetic is often described as refined, balanced, and elegant.

In essence, the Classical period reacted against the perceived excesses of the Baroque, seeking a more restrained and structurally defined style. However, the Classical period built upon the foundations laid by the Baroque, particularly in areas such as instrumental technique and compositional forms.

Q 2. Analyze the harmonic structure of a given Bach prelude.

To analyze the harmonic structure of a Bach prelude, we need a specific prelude. Let’s hypothetically consider the Prelude No. 1 in C major from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I. This prelude is relatively simple, showcasing Bach’s mastery of counterpoint and harmony within a concise form.

The piece predominantly uses diatonic harmony (the chords built from the notes of the C major scale). The harmonic progressions are relatively straightforward, often using I-IV-V-I (tonic-subdominant-dominant-tonic) and similar cadences. However, even within this seemingly simple framework, Bach utilizes subtle harmonic shifts and suspensions to create interest and tension. For example, he might momentarily introduce a secondary dominant chord (a dominant chord of a dominant chord) to temporarily modulate to a related key before resolving back to C major. The use of passing chords and neighboring chords adds further color and movement to the harmonic landscape.

A deeper analysis would involve examining:

- Key Changes: While primarily in C major, the prelude might feature brief modulations to closely related keys (like G major or F major) to add harmonic variety.

- Inversions: Bach cleverly uses inversions of chords (changing the bass note) to create different voice leading and textural effects.

- Non-Harmonic Tones: The presence of passing tones, suspensions, and appoggiaturas adds rhythmic and harmonic complexity.

Analyzing the harmonic structure requires careful listening and score study, identifying chord changes, their functions within the key, and the composer’s skillful use of non-harmonic tones to create a rich and varied harmonic texture.

Q 3. Discuss the influence of Gregorian chant on later musical styles.

Gregorian chant, the monophonic liturgical music of the medieval Roman Catholic Church, profoundly influenced the development of Western music. Its impact can be seen across centuries and diverse genres.

- Modal Harmony: Gregorian chant is based on church modes (scales different from major and minor), which heavily influenced the modal harmonies found in Renaissance and even Baroque music. Composers borrowed these modes to create a distinctive sound that evoked a specific atmosphere or emotion.

- Melodic Structure: The simple yet expressive melodies of Gregorian chant provided a foundation for later vocal music. The use of melodic phrases, cadences, and ornamentation were adopted and developed in polyphonic compositions (music with multiple independent melodic lines).

- Text Setting: The syllabic (one note per syllable) and neumatic (a few notes per syllable) techniques used in Gregorian chant were adapted and expanded upon in the setting of liturgical texts for polyphonic masses and motets.

- Liturgical Influence: The overall solemnity and spirituality associated with Gregorian chant shaped the aesthetic and function of religious music for centuries. Composers continually sought to evoke the same sense of awe and reverence in their own compositions, whether sacred or secular.

Essentially, Gregorian chant served as a foundational building block. While its simple monophonic texture evolved into the complex polyphony of later periods, its melodic contours, modal harmonies, and spiritual ethos continued to resonate throughout the history of Western music.

Q 4. Explain the development of opera during the Renaissance.

Opera’s development during the Renaissance (roughly 1400-1600) wasn’t a sudden explosion, but rather a gradual evolution from earlier forms. While the first fully-fledged operas emerged in the early Baroque period, the seeds were sown during the Renaissance.

Key elements that foreshadowed opera’s rise:

- Florentine Camerata: This group of intellectuals and artists in late 16th-century Florence sought to revive ancient Greek drama through music. Their experiments with combining poetry, music, and drama laid the groundwork for opera’s dramatic structure and vocal styles.

- Intermedii: These were short musical entertainments performed between acts of plays, often featuring mythological stories and elaborate stage effects. They provided a model for opera’s integration of music and spectacle.

- Madrigals: These secular vocal works, popular during the Renaissance, featured expressive melodies and dramatic word-painting. The expressive power of the madrigal significantly influenced the vocal styles used in early opera.

- Development of Instrumental Music: The growing sophistication of instrumental music provided a richer sonic backdrop for operatic performances.

While the Renaissance didn’t produce fully formed operas in the way we understand them today, its contributions to dramatic expression, vocal techniques, and the blending of music and theatre were crucial to the genre’s subsequent flourishing in the Baroque era. The Florentine Camerata’s experiments, in particular, are often cited as a pivotal moment in opera’s genesis.

Q 5. Describe the characteristics of the Romantic musical period.

The Romantic period in music (roughly 1780-1900), a reaction against the perceived formality and restraint of Classicism, emphasized emotional intensity, individualism, and a wide range of expression. It’s characterized by several key traits:

- Emotional Expression: Composers explored a vast spectrum of emotions, from ecstatic joy to profound sorrow, and often focused on subjective experiences rather than objective forms.

- Expanded Forms and Structures: Romantic composers often pushed the boundaries of established forms, creating longer, more expansive works with greater harmonic complexity.

- Program Music: A rise in program music—instrumental pieces that tell a story or evoke a particular image or mood—became a hallmark of the period, blurring the lines between instrumental and vocal music.

- Chromaticism and Dissonance: Composers made extensive use of chromaticism (notes outside the diatonic scale) and dissonance (unresolved chords) to create tension, dramatic effect, and a wider palette of sounds.

- Rise of Nationalism: Romantic composers often incorporated folk melodies and rhythms from their native countries, fostering a sense of national identity in their music. Examples include the use of Slavic folk music by composers like Dvořák.

- Individualism: The Romantic era saw a focus on the individual composer’s unique style and emotional expression, leading to a more personal and intimate approach to music making.

Think of the passionate melodies of Chopin, the dramatic symphonies of Beethoven (particularly his later works which bridge the Classical and Romantic eras), the expansive operas of Wagner, and the rich orchestral colors of Tchaikovsky. These composers exemplify the profound emotional depth and expressive power that defines the Romantic musical era.

Q 6. Analyze the form and structure of a sonata-allegro movement.

The sonata-allegro form is a cornerstone of Classical and Romantic instrumental music. It’s a multi-sectional structure typically found in the first movement of sonatas, symphonies, concertos, and string quartets. Its defining characteristic is its dramatic arc of exposition, development, and recapitulation.

- Exposition: Introduces the main themes (usually two contrasting themes, the first in the tonic key and the second in a related key—often the dominant). The exposition often repeats.

- Development: This section explores the themes presented in the exposition, often fragmenting them, modulating to different keys, and creating harmonic tension. This is often the most dramatic and improvisational-sounding section.

- Recapitulation: The main themes return, usually in the tonic key. The recapitulation reestablishes the musical equilibrium after the tension built in the development section. Often the second theme is now also in the tonic key.

- Coda (optional): A concluding section that might offer a final flourish or extension of the thematic material.

Think of the first movement of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. Its iconic opening motif is the main theme, developed and transformed throughout the movement before returning triumphantly in the recapitulation. The sonata-allegro form provides a framework for dramatic narrative and musical exploration, balancing unity and variety in a highly effective structure.

Q 7. Discuss the impact of technology on music history.

Technology has profoundly impacted music history, from its creation and distribution to its consumption and experience. Here are some key examples:

- Recording Technology: The invention of the phonograph in the late 19th century revolutionized music. It allowed for the mass production and distribution of music, creating a wider audience and preserving performances for posterity. Later developments, such as magnetic tape and digital recording, have continuously improved sound quality and accessibility.

- Electronic Instruments: The invention of the synthesizer and other electronic instruments broadened the sonic possibilities, opening new avenues for musical experimentation and composition. Electronic music has become a major genre in its own right, evolving from early experiments to complex and nuanced styles.

- Digital Music Production: Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs) have democratized music production, enabling musicians with limited resources to create high-quality recordings. This technology has fostered a more diverse and independent music scene.

- Music Streaming and Distribution: Online platforms like Spotify and Apple Music have transformed how people consume music. They offer immense catalogs of music instantly accessible to a global audience, impacting the business model and creative practices of the music industry.

- Social Media and Collaboration: Social media platforms allow musicians to connect with audiences, collaborate on projects, and share their music easily. This increased accessibility has led to new forms of music creation and community building.

In conclusion, technological advancements have not only changed how music is created, distributed, and consumed but have also shaped its stylistic evolution and the cultural context in which it is experienced. The impact of technology continues to evolve rapidly, creating both opportunities and challenges for musicians and listeners alike.

Q 8. Explain the concept of musical form and its evolution.

Musical form refers to the overall structure and organization of a musical work. Think of it like the blueprint of a house – it dictates how different sections fit together to create a cohesive whole. Its evolution is a fascinating journey reflecting changing aesthetics and expressive needs across different eras.

Early Forms (Medieval & Renaissance): Simple forms like the cantus firmus mass, where a pre-existing melody formed the foundation, were common. Later, the development of binary (two-part) and ternary (three-part) forms provided more structural complexity.

Baroque Period: The Baroque witnessed a flourishing of elaborate forms, including the concerto grosso (alternating between a small group of soloists and a larger ensemble), the fugue (a contrapuntal form based on a recurring theme), and the sonata (a multi-movement work often featuring contrasting sections).

Classical Period: The Classical period standardized forms like the sonata-allegro form (exposition, development, recapitulation), the minuet and trio, and the rondo (a recurring main theme interspersed with contrasting episodes). These forms offered a sense of balance and clarity.

Romantic Period and Beyond: Romantic composers often pushed the boundaries of established forms, creating larger, more expansive structures. Later developments included the rise of atonal and serial music, where traditional formal structures were often abandoned or radically altered.

Understanding musical form is crucial for both composers and analysts. It allows composers to craft compelling narratives and listeners to grasp the overall architecture of a piece.

Q 9. How did the patronage system influence the composition of music in the Renaissance?

The patronage system in the Renaissance profoundly shaped musical composition. Composers, instead of relying on public concerts, depended on wealthy patrons – royalty, the Church, and the nobility – for their livelihood and artistic direction. This relationship dictated the style, subject matter, and even the length of compositions.

Church Patronage: Church patrons commissioned sacred music, masses, motets, and hymns, reflecting liturgical needs and theological ideals. Composers like Josquin des Prez wrote extensively for the Church, showcasing the influence of religious doctrine on musical form and content.

Royal and Noble Patronage: Secular patrons commissioned music for courtly entertainment – dances, songs, and instrumental works. The demands of the court impacted the development of secular genres like madrigals and chansons. Composers like William Byrd composed for both the English court and the Church, demonstrating the duality of patronage influences.

Impact on Style: Patronage influenced musical style directly. Patron preferences dictated the use of certain instruments, vocal ranges, and musical textures. For instance, the opulent style of the Italian Renaissance reflected the lavish lifestyles of its patrons.

The patronage system, while providing stability for some composers, also presented constraints. Composers often had to tailor their works to suit their patrons’ tastes, sometimes compromising their artistic vision.

Q 10. What are the key features of twelve-tone composition?

Twelve-tone composition, also known as serialism, is a compositional technique developed in the early 20th century, primarily associated with Arnold Schoenberg. It aims to create atonal music, avoiding the traditional hierarchy of pitches within a key, by using a twelve-tone row.

The Twelve-Tone Row (Series): The core principle is the creation of a twelve-tone row, a sequence containing each of the twelve chromatic pitches exactly once, in a specific order. This row forms the basis for the entire composition.

Transformations of the Row: The row can be transformed in four main ways: inversion (mirroring the pitches around a central axis), retrograde (playing the row backwards), retrograde inversion (playing the inversion backwards), and prime (the original row).

Organization and Development: These row forms are interwoven throughout the composition to create thematic material and harmonic progressions. This ensures that no single pitch dominates, creating a sense of equal importance for all twelve tones.

Abolition of Tonality: The technique deliberately avoids any sense of tonal center or key, resulting in music that lacks the traditional feeling of harmonic resolution or pull toward a specific pitch.

Twelve-tone composition represents a radical departure from tonal music and had a profound impact on the development of 20th-century music. While initially controversial, it opened up new avenues of musical exploration.

Q 11. Compare and contrast the compositional techniques of Bach and Beethoven.

Johann Sebastian Bach and Ludwig van Beethoven, though separated by time and style, are titans of Western music. Comparing their compositional techniques reveals fascinating contrasts and shared strengths.

Bach (Baroque): Bach’s compositions are characterized by intricate counterpoint, where multiple independent melodic lines weave together harmoniously. He masterfully used fugues, inventions, and other contrapuntal techniques to create complex and intellectually stimulating music. His harmonic language is predominantly Baroque, rooted in major and minor keys but exhibiting rich chromaticism within the framework of tonality.

Beethoven (Classical/Romantic): Beethoven built upon Classical forms but expanded their expressive possibilities. His music is characterized by dramatic contrasts, powerful dynamics, and a heightened emotional range. While skilled in counterpoint, his works often feature simpler textures than Bach’s, focusing on melodic development and thematic transformation. His harmonic language is more adventurous, venturing into wider key changes and modulations, ultimately paving the way for Romantic harmonic freedom.

Similarities: Both composers demonstrated exceptional mastery of form and structure. Both were innovative in their respective periods, pushing the boundaries of their era’s conventions.

In essence, Bach’s genius lies in his intricate contrapuntal textures and masterful use of Baroque forms, whereas Beethoven’s lies in his dramatic storytelling, emotional depth, and innovative development of Classical forms into a Romantic expression.

Q 12. Analyze a given musical excerpt, identifying its key, meter, and texture.

To analyze a musical excerpt for key, meter, and texture, a systematic approach is necessary. Unfortunately, I cannot analyze a musical excerpt directly as I am a text-based AI. However, I can outline the process.

Key: Identify the tonal center – the note around which the music gravitates. Listen for the predominant chords and the feeling of resolution towards a specific pitch. Analyzing the bass line and identifying the dominant and tonic chords is often helpful.

Meter: Determine the rhythmic organization – how the music is divided into beats and measures. Count the beats per measure and note the type of note (whole, half, quarter, etc.) that receives one beat. Common meters include 4/4 (common time), 3/4 (waltz time), and 6/8.

Texture: Describe the layering of sound – how many independent melodic lines are present (monophony: one line, homophony: melody with accompaniment, polyphony: multiple independent melodies). Note the interplay between the different layers and the overall density of the music.

Analyzing a musical excerpt is a combination of listening carefully and applying theoretical knowledge. It’s like solving a musical puzzle – the pieces are the notes, rhythms, and harmonies, and the solution is a clear understanding of the music’s fundamental components.

Q 13. Discuss the contributions of a specific composer to music history.

Clara Schumann (1819-1896) made significant contributions to music history, despite the challenges she faced as a female composer in the 19th century. Her legacy extends beyond her own compositions to encompass her profound influence on her husband, Robert Schumann, and her role as a pioneering female pianist and teacher.

Compositional Style: Clara Schumann’s compositions demonstrate a mastery of Romantic style, blending lyricism, emotional depth, and technical brilliance. Her piano works, including her piano concertos and character pieces, are particularly notable for their expressive power and virtuosity.

Influence on Robert Schumann: Clara’s musical talent was recognized early on, and her critiques and insights provided invaluable feedback to Robert during his compositional process. Their collaborative relationship underscores the importance of reciprocal artistic influence.

Pioneering Role for Women: Clara’s success as a performer and composer challenged societal norms, paving the way for future generations of female musicians. She overcame significant obstacles to establish herself as a prominent figure in the musical world.

Clara Schumann’s contributions are a testament to her talent and perseverance. She stands as an example of a composer whose work and influence resonate even today, demonstrating the richness and complexity of 19th-century musical life and underscoring the historical significance of overcoming gender barriers in the arts.

Q 14. Explain the concept of tonality and its evolution.

Tonality refers to the organization of pitches around a central tone, the tonic, creating a sense of key and harmonic direction. Its evolution reflects fundamental shifts in musical aesthetics and compositional practices.

Early Tonality (Medieval & Renaissance): Early forms of tonality were less defined than later periods. Modal music, based on church modes rather than major and minor scales, was prevalent. The concept of a clear tonal center was still developing.

Common Practice Period (Baroque, Classical, Romantic): This period saw the consolidation of major and minor keys as the foundation of tonality. Composers used harmonic progressions, cadences, and modulation to create a sense of tonal direction and harmonic resolution. The functional harmony – the relationship between chords within a key – became central to compositional technique.

Late Romanticism & 20th Century: Late Romantic composers, like Wagner, explored chromaticism and extended tonality, blurring the lines between keys. The 20th century witnessed a move away from traditional tonality altogether, with the rise of atonal and serial music, as explored in twelve-tone composition.

Post-Tonal and Beyond: Contemporary music embraces diverse approaches to pitch organization, encompassing microtonality, atonality, and a variety of other systems. Tonality remains influential, but its dominance is challenged by a wider range of compositional approaches.

The evolution of tonality mirrors the ever-changing landscape of musical expression. Understanding its trajectory is crucial to interpreting music across historical periods and appreciating the diversity of musical styles.

Q 15. Describe the different types of musical notation used throughout history.

Musical notation, the system for writing down music, has evolved dramatically throughout history. Early forms were rudimentary, focusing primarily on melodic contours.

- Ancient Greek Notation: Used a combination of letters and symbols to represent pitch and rhythm, but lacked precision in expressing dynamics or complex rhythmic patterns. Think of it like a very basic outline of a song, missing many details.

- Neumatic Notation: Developed in the medieval era, this system used small symbols or neumes above the text to indicate the general melodic shape. Imagine it as a simplified shorthand for singers, more about the general direction of the melody than exact pitches.

- Mensural Notation: From the late Middle Ages, this system introduced more precise rhythmic notation using various note shapes and symbols representing different note durations. This is a big step forward, allowing for more complex rhythms to be written down accurately.

- Modern Notation: Developed from the Renaissance onwards, this system, based on the five-line staff and musical symbols we recognize today, provides a comprehensive and precise system for representing pitch, rhythm, dynamics, articulation, and other musical elements. Think of this as a complete blueprint of the music, allowing for accurate reproduction.

Each system reflects the musical capabilities and theoretical understanding of its time, demonstrating a gradual evolution towards greater expressiveness and precision.

Career Expert Tips:

- Ace those interviews! Prepare effectively by reviewing the Top 50 Most Common Interview Questions on ResumeGemini.

- Navigate your job search with confidence! Explore a wide range of Career Tips on ResumeGemini. Learn about common challenges and recommendations to overcome them.

- Craft the perfect resume! Master the Art of Resume Writing with ResumeGemini’s guide. Showcase your unique qualifications and achievements effectively.

- Don’t miss out on holiday savings! Build your dream resume with ResumeGemini’s ATS optimized templates.

Q 16. What is the significance of the ‘Sprechstimme’ technique?

Sprechstimme, German for ‘speaking voice,’ is a vocal technique pioneered by Arnold Schoenberg, where the singer declaims the text on pitches indicated by the composer, but without the full, sustained notes of singing. It sits somewhere between speech and song.

Its significance lies in its ability to bridge the gap between vocal and instrumental expression. It creates a unique atmosphere of heightened tension and emotional intensity, often associated with the expression of angst or inner turmoil. The pitch is approximate rather than precise, allowing for a more natural, emotive vocalization which is closer to the natural inflection of spoken language.

Schoenberg used Sprechstimme extensively in his Pierrot Lunaire, where the unsettling nature of the poetry is perfectly mirrored by the ambiguous and unsettling character of the vocal delivery. It’s a technique that has been adopted by other composers, demonstrating its enduring influence on vocal expression and compositional techniques.

Q 17. Discuss the influence of folk music on classical composers.

Folk music has profoundly influenced classical composers throughout history. Classical composers often drew inspiration from folk melodies, rhythms, and harmonies, integrating them into their works to create a distinctly national or regional character.

For example, many of Antonín Dvořák’s compositions, such as his New World Symphony, incorporate elements of American folk music. Similarly, Béla Bartók extensively studied and incorporated Hungarian folk music into his compositions, preserving and promoting the rich musical heritage of his country. Think of it as a composer taking inspiration from the everyday music of the people, giving it a new context and elevated expression.

This integration wasn’t simply about borrowing melodies; it involved adapting the harmonic language, rhythmic patterns, and even the formal structures of folk music into the larger framework of classical compositional techniques. This interaction enriched the classical idiom and helped to create a more diverse and representative musical landscape.

Q 18. Analyze the use of dissonance and consonance in a given musical work.

To analyze the use of dissonance and consonance in a specific musical work, we need a concrete example. Let’s consider the opening of Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring.

The piece famously begins with a jarring, dissonant chord that immediately establishes a sense of unease and primal energy. This dissonance, the clash of notes considered unpleasant or unstable, is used strategically to create a sense of tension and disruption. Throughout the work, Stravinsky frequently employs dissonant harmonies to express the raw power and primitive energy depicted in the ballet’s narrative.

However, consonance, the combination of notes that sound pleasing and stable, also plays a role, although often in a subordinate manner. Consonant moments provide brief respites or contrasting textures, highlighting the impact of the dissonant passages by offering moments of relative calm before returning to the tension and unease.

The interplay of dissonance and consonance in The Rite of Spring is not just about creating pleasant or unpleasant sounds, but rather a sophisticated technique used to generate a potent emotional effect. This use of harmonic tension and release is a central aspect of the work’s groundbreaking nature.

Q 19. Explain the development of musical instruments throughout history.

The development of musical instruments is a long and fascinating journey, mirroring technological advancements and evolving musical aesthetics.

- Ancient Instruments: Early instruments were often simple, utilizing natural materials like wood, animal hide, and bone. Examples include flutes made from bone or reeds, and percussion instruments made from hollowed-out logs or animal skins. Think of the basic functionality of these instruments, simple tools used to create sound.

- Medieval and Renaissance Instruments: Saw significant advancements, with the development of more complex stringed, wind, and percussion instruments. The lute, recorder, and various types of harps became prevalent, demonstrating sophistication in craftsmanship and expanding musical possibilities.

- Baroque and Classical Periods: Witness the refinement of existing instruments and the emergence of standardized forms. The violin family, harpsichord, and organ reached a high point of development, providing a wider range of expressive possibilities. The standardization of instrument design was crucial for ensemble music.

- Romantic and Modern Eras: Continued innovation, with improvements to existing instruments and the invention of new ones. The piano’s evolution is a prime example, with improvements in mechanisms and sound production. The development of electronic instruments in the 20th century revolutionized music once again.

This evolution reflects not only technological progress but also the changing demands of musical styles and aesthetics. Each period saw improvements in craftsmanship, intonation, and expressive capacity, expanding the possibilities for musical expression.

Q 20. Discuss the impact of nationalism on musical styles.

Nationalism profoundly impacted musical styles, often leading to the development of distinct national schools of composition. Composers sought to express the unique character and cultural identity of their nations through music.

For example, the rise of Russian nationalism in the 19th century inspired composers like Modest Mussorgsky and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov to incorporate folk melodies, rhythms, and harmonies into their works, creating a distinctly Russian musical style. Think of the vibrant colors and powerful emotional intensity characteristic of their compositions, reflecting the spirit of their homeland.

Similarly, composers in other countries, such as Bedřich Smetana in Bohemia and Edvard Grieg in Norway, developed nationalistic styles that reflected the specific cultural characteristics of their respective nations. The use of folk materials, unique melodic contours, and characteristic harmonic languages helped create musical expressions that resonated with national pride and identity.

This nationalistic fervor in music was not just about aesthetics; it also served as a powerful tool for political and cultural expression, solidifying national identity and fostering a sense of shared heritage.

Q 21. How did the rise of recording technology impact music composition and performance?

The rise of recording technology had a transformative impact on music composition and performance. Before recording, music was a live experience, subject to the limitations of memory and the variability of each performance.

Recording technology allowed for the preservation and dissemination of music on an unprecedented scale. Composers could now hear and analyze their work in a way that was never before possible, leading to a greater level of refinement and control. Performers could study recordings of great musicians, leading to improved technique and interpretation. This access to musical performances from around the world broadened musical horizons.

However, recording technology also introduced new challenges. The focus on creating commercially viable recordings sometimes influenced compositional choices, and the emphasis on perfect performances potentially diminished the spontaneous and improvisational aspects of live music. The accessibility of recorded music also changed the way music was consumed and valued, raising complex questions about the relationship between the studio recording and the live performance.

Ultimately, recording technology has become an integral part of the musical landscape, profoundly changing the way music is created, performed, and consumed.

Q 22. Explain the difference between absolute and program music.

The fundamental difference between absolute and program music lies in their relationship to extra-musical narratives. Absolute music, also known as instrumental music, is self-contained and doesn’t tell a story or depict a specific scene. Its meaning is derived solely from its musical elements—melody, harmony, rhythm, form, and timbre. Think of a classical sonata or symphony; the listener experiences the music for its inherent beauty and structure, without needing a pre-existing narrative to understand it.

Program music, conversely, is intended to evoke a story, poem, painting, or other extra-musical concept. The composer provides a narrative or descriptive program to guide the listener’s interpretation. Famous examples include Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, which depicts a drug-induced dream, or Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, inspired by paintings. While both forms utilize similar musical elements, the intended listener experience differs significantly: one focuses on intrinsic musical values, the other on a narrative interpretation enhanced by the music.

Q 23. What are some key characteristics of Minimalist music?

Minimalist music, a significant movement emerging in the late 20th century, is characterized by its emphasis on repetition, gradual change, and a limited number of musical ideas. Key characteristics include:

- Repetitive structures: Simple melodic and rhythmic motifs are repeated over extended periods, often with subtle variations.

- Gradual transformation: These repetitions aren’t static; the music slowly evolves through minor alterations in pitch, rhythm, or timbre.

- Limited melodic and harmonic materials: A small range of pitches and chords is often used, creating a sense of simplicity and focus.

- Emphasis on texture and timbre: The interplay of different instrumental sounds and textures contributes significantly to the overall effect, sometimes overshadowing traditional melodic development.

- Often drone-based: A sustained low-pitched note or chord (drone) frequently underlies other musical elements, providing a grounding sonic base.

Composers like Steve Reich, Philip Glass, and Terry Riley are pioneers of this style. Think of Reich’s Clapping Music, where simple clapping patterns gradually shift out of phase, creating a complex and mesmerizing texture through subtle transformation.

Q 24. Describe the relationship between music and society in a specific historical period.

The relationship between music and society in the Baroque period (roughly 1600-1750) is a fascinating study. Music wasn’t simply an art form; it was deeply intertwined with religious, social, and political life.

In the Catholic church, music played a crucial role in liturgical services. Grand, elaborate masses and motets were composed for large ensembles, reflecting the church’s power and influence. The development of the opera, initially for aristocratic courts, also reflects societal structures. Operas were elaborate spectacles, showcasing not only musical talent but also lavish costumes, staging, and theatrical skills, mirroring the extravagance and social hierarchies of the time.

The rise of the public concert also marked a shift. While initially for the elite, concerts gradually became more accessible, creating a new public space for musical experience and social interaction. The emergence of music publishing further contributed to a growing musical culture beyond the confines of church and court, making music more available and accessible to a broader audience. In essence, Baroque music reflected and shaped the social and political climate of the era, mirroring its grandeur, religious fervor, and increasing secularization.

Q 25. Analyze the use of counterpoint in a given Renaissance motet.

To analyze the use of counterpoint in a Renaissance motet, let’s consider Josquin des Prez’s Ave Maria…virgo serena as an example. The piece demonstrates the sophisticated polyphonic textures characteristic of the Renaissance. Analysis involves identifying the different independent melodic lines (voices) and examining how they interweave.

Josquin masterfully uses imitation, where a melodic phrase is presented in one voice and then repeated or varied in another. This creates a sense of unity and interconnectedness between the voices. He also employs point of imitation, where imitation begins at different times, giving the texture a dynamic feel. The use of canons, where one or more voices echo another at a precise interval, is also evident, contributing to the piece’s intricate structure.

Further analysis would consider the textural relationships between the voices: are they independent throughout, or do they sometimes combine in homophonic passages? Also crucial is how the composer manages voice leading—the smooth and logical movement of individual voices—to avoid clashes or awkward harmonies. Analyzing the harmonic progressions underlying the counterpoint helps to understand the overall tonal framework. By meticulously examining these elements, we can appreciate the complexity and artistry of Josquin’s counterpoint, revealing his mastery of the compositional techniques of his time.

Q 26. Discuss the development of musical form in the 20th century.

The 20th century witnessed a radical upheaval in musical form, largely breaking away from the established structures of the Classical and Romantic eras. Several key developments include:

- Serialism: This technique, championed by Schoenberg and his followers, systematically organized pitches, rhythms, and dynamics in predetermined series, rejecting traditional tonality.

- Atonality and 12-tone music: Abandonment of the traditional tonal hierarchy, exploring all twelve notes of the chromatic scale equally.

- Neoclassicism: A reaction against Romanticism, embracing clarity, balance, and formal structures inspired by earlier eras, often with a more restrained emotional palette.

- Minimalism: The emphasis on repetition, gradual change, and limited musical materials, as discussed earlier.

- Aleatoric music (chance music): Incorporating elements of chance and spontaneity, allowing for varying interpretations and performances.

- Electronic music: The advent of electronic instruments and synthesizers opened up entirely new sonic possibilities, influencing a wide range of musical styles.

These developments didn’t replace previous forms but rather added new layers of complexity and diversity. Composers often blended different techniques, resulting in a rich tapestry of musical styles, each challenging and expanding the boundaries of musical expression.

Q 27. Explain the concept of musical analysis and its different methodologies.

Musical analysis is the systematic study of music to understand its structure, meaning, and aesthetic impact. It involves breaking down a piece into its constituent parts and examining how they function together. Different methodologies exist, each providing unique insights:

- Formal analysis: Examines the overall structure and organization of a piece, identifying sections, themes, and their relationships (e.g., sonata form, rondo form).

- Harmonic analysis: Focuses on the chord progressions and harmonic relationships within a piece, analyzing function, tension, and resolution.

- Melodic analysis: Studies the melodic contours, intervals, and motives, identifying the primary melodic ideas and their development.

- Rhythmic analysis: Investigates the rhythmic patterns, meters, and rhythmic relationships, identifying rhythmic motives and their transformations.

- Textural analysis: Examines the interaction of different musical lines and voices, describing the texture as monophonic, polyphonic, homophonic, etc.

- Semiotic analysis: Explores the meaning and significance of musical elements, considering cultural and social contexts.

These methodologies are often used in combination to provide a comprehensive understanding of a musical work. For example, analyzing a Baroque concerto might involve formal analysis to identify the structure of the movements, harmonic analysis to examine the interplay between the soloist and orchestra, and textural analysis to describe the contrasting textures between the tutti and solo sections.

Q 28. How has the study of music history changed over time?

The study of music history has undergone significant transformations over time. Early approaches, often rooted in biographical narratives and stylistic classifications, focused heavily on Western art music and its prominent composers. This perspective, however, has been increasingly challenged.

Modern music history scholarship incorporates broader perspectives, including:

- Ethnomusicology: The study of music in its cultural and social context, moving beyond Western traditions to encompass diverse musical cultures worldwide.

- Gender studies: Examining the roles of women in music history, often overlooked in earlier scholarship.

- Social history: Considering the social, economic, and political factors shaping musical production and consumption.

- Critical theory: Applying theoretical frameworks to interpret music’s meaning and impact within power structures and social ideologies.

Today’s music historians use diverse methodologies, drawing on archival research, analysis of musical scores, and ethnographic fieldwork. The focus has shifted from simple chronological narratives to more nuanced and critical engagements with music’s multifaceted role in human societies. This evolution reflects a growing awareness of the limitations of previous approaches and a commitment to more inclusive and comprehensive understandings of music’s rich and diverse history.

Key Topics to Learn for Your Music History and Analysis Interview

Ace your interview by mastering these crucial areas of Music History and Analysis. Remember, a deep understanding of these concepts, combined with the ability to apply them practically, will significantly boost your confidence and performance.

- Periods and Styles: Develop a comprehensive understanding of major musical periods (e.g., Baroque, Classical, Romantic, 20th Century) and their defining stylistic characteristics. Be prepared to discuss representative composers and their works.

- Musical Forms and Structures: Master the analysis of musical forms (e.g., sonata form, rondo, fugue) and understand how these structures contribute to a piece’s overall aesthetic impact. Practice analyzing scores to identify formal elements.

- Harmony and Counterpoint: Demonstrate a strong grasp of harmonic principles and the ability to analyze contrapuntal textures. Be ready to discuss different harmonic progressions and their expressive functions.

- Melody and Rhythm: Understand the role of melody and rhythm in shaping musical expression. Be prepared to discuss melodic contour, rhythmic patterns, and their relationship to form and harmony.

- Instrumentation and Orchestration: Develop knowledge of different instruments and their capabilities, as well as the art of orchestration and its effect on musical texture and color. Practice analyzing orchestral scores.

- Historical Context and Cultural Influences: Discuss the historical and cultural contexts that shaped musical styles and the impact of social, political, and technological factors on musical development.

- Analytical Methodologies: Familiarize yourself with different analytical approaches (e.g., Schenkerian analysis, narratological analysis) and be able to discuss their strengths and limitations.

Next Steps: Unlock Your Career Potential

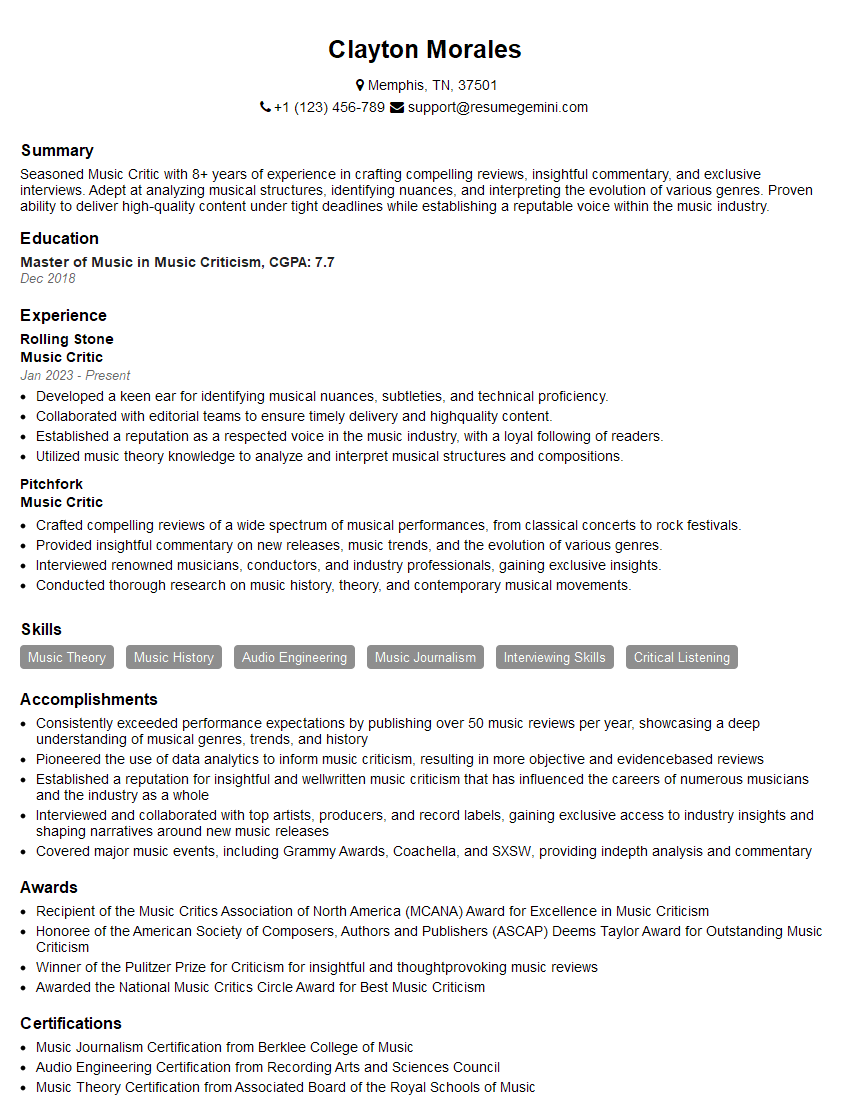

Mastering Music History and Analysis is vital for a successful career in musicology, music education, or related fields. A strong understanding of these concepts demonstrates your expertise and analytical skills, making you a highly competitive candidate. To further enhance your job prospects, create an ATS-friendly resume that effectively highlights your skills and experience.

We recommend using ResumeGemini, a trusted resource for building professional and impactful resumes. ResumeGemini can help you craft a resume that gets noticed by recruiters. Examples of resumes tailored specifically for Music History and Analysis positions are available to guide you.

Explore more articles

Users Rating of Our Blogs

Share Your Experience

We value your feedback! Please rate our content and share your thoughts (optional).

What Readers Say About Our Blog

To the interviewgemini.com Webmaster.

Very helpful and content specific questions to help prepare me for my interview!

Thank you

To the interviewgemini.com Webmaster.

This was kind of a unique content I found around the specialized skills. Very helpful questions and good detailed answers.

Very Helpful blog, thank you Interviewgemini team.