Are you ready to stand out in your next interview? Understanding and preparing for Physical Examination and Diagnosis interview questions is a game-changer. In this blog, we’ve compiled key questions and expert advice to help you showcase your skills with confidence and precision. Let’s get started on your journey to acing the interview.

Questions Asked in Physical Examination and Diagnosis Interview

Q 1. Describe the proper technique for assessing heart sounds.

Assessing heart sounds, or auscultation, is a fundamental skill in cardiology. It involves carefully listening to the sounds produced by the heart’s valves and chambers. The process requires a quiet environment, a good quality stethoscope, and a systematic approach.

- Position: Begin by having the patient lie supine. Auscultate with the patient in various positions (sitting, leaning forward) as certain sounds might be accentuated.

- Landmarks: Familiarize yourself with the key auscultatory areas: aortic (2nd right intercostal space), pulmonic (2nd left intercostal space), tricuspid (lower left sternal border), and mitral (5th intercostal space, mid-clavicular line).

- Technique: Use the diaphragm of the stethoscope for high-pitched sounds (e.g., S1, S2, most murmurs) and the bell for low-pitched sounds (e.g., S3, S4, some murmurs). Apply light pressure with the diaphragm and slightly firmer pressure with the bell. Listen at each location for at least one full cardiac cycle. Pay close attention to the timing, intensity, location, pitch, and quality of the sounds.

- Rhythm and Rate: Note the regularity of the heartbeat and count the rate for a full minute. Identify any arrhythmias or irregularities.

Example: Imagine you hear a harsh, systolic murmur at the left sternal border. This could indicate a potential problem with the pulmonic valve. However, further investigation would be needed to confirm the diagnosis.

Q 2. Explain the steps involved in performing a neurological examination.

A neurological exam systematically assesses the different aspects of the nervous system. It’s crucial to follow a structured approach for accurate and comprehensive evaluation.

- Mental Status: Assess level of consciousness, orientation, attention, memory, and cognitive function. A simple question like ‘What is your name and where are you?’ can reveal crucial information.

- Cranial Nerves: Test the twelve cranial nerves individually (I-XII) using specific maneuvers; for example, checking pupillary response to light (CN II, III), facial symmetry (CN VII), and gag reflex (CN IX, X).

- Motor System: Evaluate muscle strength, tone, bulk, and involuntary movements. Asking the patient to raise their arms against resistance, assess gait, and examine for tremors are all part of this.

- Sensory System: Assess different sensations like light touch, pain, temperature, and proprioception (sense of position) in different parts of the body. A pinprick test is commonly used to check pain sensation.

- Reflexes: Examine deep tendon reflexes (patellar, biceps, triceps) and superficial reflexes (abdominal, plantar). A brisk or absent reflex could point towards underlying neurological issues.

- Coordination and Cerebellar Function: Test coordination with tasks like finger-to-nose and heel-to-shin testing. Balance and gait analysis also fall under this section.

Example: During a neurological examination, if a patient shows weakness on one side of the body along with altered reflexes, it can suggest a stroke or other neurological damage requiring immediate attention. Careful documentation of all findings is critical.

Q 3. How do you differentiate between different types of murmurs?

Differentiating murmurs requires careful attention to detail. Key factors include timing, location, radiation, intensity, pitch, and quality.

- Timing: Is the murmur systolic (during ventricular contraction) or diastolic (during ventricular relaxation)? Systolic murmurs are more common.

- Location: Where is the murmur loudest? This often helps pinpoint which valve is involved.

- Radiation: Does the murmur radiate to other areas? For example, a murmur radiating to the carotid arteries might suggest aortic stenosis.

- Intensity (Grade): Murmurs are graded on a scale of I-VI, with I being barely audible and VI being easily palpable. This gives an idea of the severity.

- Pitch: Is the murmur high-pitched or low-pitched? This can help distinguish between different pathologies.

- Quality: Is the murmur harsh, blowing, rumbling, musical, or other descriptive terms? These qualities help describe the character of the murmur.

Example: A harsh, crescendo-decrescendo systolic murmur heard best at the right second intercostal space that radiates to the carotid arteries is highly suggestive of aortic stenosis. Conversely, a low-pitched diastolic rumble heard at the apex might suggest mitral stenosis.

Q 4. What are the key components of a comprehensive respiratory examination?

A comprehensive respiratory exam involves a systematic assessment of the respiratory system, focusing on both inspection and auscultation.

- Inspection: Observe the patient’s respiratory rate, rhythm, depth, and effort. Look for any signs of respiratory distress, such as nasal flaring, use of accessory muscles, or cyanosis. Note the shape and symmetry of the chest wall.

- Palpation: Assess chest expansion by placing your hands on the patient’s back and observing symmetrical movement during respiration. Palpate for any tenderness, masses, or crepitus (a crackling sound).

- Percussion: Percuss the chest to assess the underlying lung tissue. Dullness may suggest consolidation, while hyper-resonance might indicate pneumothorax or emphysema.

- Auscultation: Listen to breath sounds in different lung fields, comparing sounds side-to-side. Identify any adventitious sounds such as crackles (rales), wheezes, or rhonchi. These additional sounds offer clues regarding potential underlying conditions.

Example: If you detect diminished breath sounds in the right lower lobe accompanied by dullness on percussion and crackles, this could suggest pneumonia. Further investigations such as chest X-ray would be indicated.

Q 5. Explain your approach to diagnosing abdominal pain.

Diagnosing abdominal pain requires a thorough and systematic approach. It often involves integrating findings from the history, physical exam, and laboratory investigations.

- History: Gather detailed information about the onset, character, location, radiation, timing, severity, associated symptoms (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, fever, changes in bowel habits), and any aggravating or relieving factors.

- Physical Examination: Begin with general observation, assessing for signs of dehydration, pallor, or distress. Proceed to a detailed abdominal exam. This includes inspection (looking for distension, scars, or masses), auscultation (listening for bowel sounds), percussion (assessing for tenderness or guarding), and palpation (gently feeling for tenderness, masses, or organomegaly).

- Laboratory Investigations: Depending on the suspected cause, various blood tests (CBC, inflammatory markers), urine tests, or imaging studies (X-ray, CT scan, ultrasound) may be ordered.

Example: A patient presenting with sudden, severe, right lower quadrant pain, fever, and rebound tenderness (pain upon release of palpation) is highly suggestive of appendicitis, and imaging and surgical consultation would likely be necessary. However, many other conditions can present with abdominal pain, emphasizing the importance of a comprehensive assessment.

Q 6. Describe the techniques used to assess skin lesions.

Assessing skin lesions involves a systematic approach using the ABCDEs of melanoma (although these criteria apply to more than just melanomas) and other key observations.

- Asymmetry: Is the lesion symmetrical or asymmetrical?

- Border: Are the borders well-defined or irregular?

- Color: Is the color uniform or variegated (multiple colors)?

- Diameter: What is the diameter of the lesion? Lesions larger than 6 mm may warrant closer attention.

- Evolution: Has the lesion changed in size, shape, or color over time?

- Location: Note the lesion’s location on the body.

- Texture: Is the lesion flat, raised, papular, nodular, or ulcerated?

- Palpation: Feel the lesion to assess its consistency, texture, and tenderness.

Example: A lesion with irregular borders, varying colors (tan, brown, black), and a diameter of 8 mm that has been growing rapidly over the last few months is highly suspicious for melanoma and needs urgent dermatological referral.

Q 7. How do you interpret abnormal lung sounds?

Interpreting abnormal lung sounds is crucial for identifying respiratory pathologies. Different sounds indicate specific underlying conditions.

- Crackles (rales): Discontinuous, popping sounds typically heard during inspiration. They suggest the presence of fluid, inflammation, or secretions in the airways (e.g., pneumonia, pulmonary edema, bronchitis).

- Wheezes: Continuous, musical sounds, usually heard during expiration but can be present on inspiration. They indicate narrowed airways, as seen in asthma, COPD, and other obstructive lung diseases.

- Rhonchi: Continuous, low-pitched, snoring sounds, often caused by mucus or secretions in larger airways. They can be heard during inspiration or expiration. Conditions like bronchitis or pneumonia can lead to rhonchi.

- Pleural Rub: A grating or creaking sound heard during both inspiration and expiration. It is usually caused by inflammation of the pleural surfaces, as seen in pleurisy.

- Diminished Breath Sounds: Reduced or absent breath sounds may suggest a collapsed lung (pneumothorax), pleural effusion, or significant airway obstruction.

Example: High-pitched wheezes throughout the lung fields, particularly during expiration, combined with shortness of breath and a history of asthma, strongly suggest an asthma exacerbation.

Q 8. What are the signs and symptoms of a stroke, and how do you assess for them?

Stroke, also known as a cerebrovascular accident (CVA), occurs when blood supply to part of the brain is interrupted. Recognizing the signs and symptoms quickly is crucial for timely intervention. The classic symptoms are often remembered by the acronym FAST:

- Facial drooping: Ask the person to smile. Does one side of the face droop?

- Arm weakness: Ask the person to raise both arms. Does one arm drift downward?

- Speech difficulty: Ask the person to repeat a simple phrase. Is their speech slurred or strange?

- Time to call 911: If you observe any of these signs, immediately call emergency services.

Beyond FAST, other symptoms can include sudden numbness or weakness on one side of the body, sudden confusion, trouble seeing in one or both eyes, trouble walking, dizziness, severe headache with no known cause. Assessment involves a thorough neurological examination, including checking for cranial nerve function, motor strength, sensory perception, reflexes, and coordination. Vital signs like blood pressure and heart rate are also monitored. A detailed history, including the time of symptom onset, is essential for guiding treatment decisions.

Example: Imagine a patient presenting with sudden right-sided weakness and slurred speech. Using FAST, we identify facial drooping on the right side and arm weakness on the right. This immediately points towards a potential stroke, necessitating immediate medical attention.

Q 9. Describe the steps involved in performing a breast examination.

Breast self-examination (BSE) and clinical breast examination (CBE) are important for early detection of breast cancer. A CBE involves a systematic approach:

- Inspection: Observe the breasts for size, shape, symmetry, skin changes (dimpling, redness, ulceration), nipple discharge, and any visible masses.

- Palpation: Palpate each breast systematically using a circular, vertical strip, or wedge pattern. Use the pads of the fingers to examine the entire breast tissue, including the axillary tail extending into the armpit. Vary the pressure during palpation (light, medium, and deep). Pay attention to any lumps, nodules, or areas of thickening.

- Nipple Examination: Gently compress the nipple to check for any discharge.

- Axillary Lymph Node Examination: Palpate the lymph nodes in the armpit (axilla) for any enlargement or tenderness.

It’s crucial to perform the examination in a comfortable, well-lit setting. The patient should be lying down or sitting comfortably. Consistency is key; regular self-exams and periodic professional examinations help detect changes early.

Example: During a CBE, I might palpate a small, hard, irregular lump in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast. This warrants further investigation, such as mammography or ultrasound.

Q 10. Explain the significance of different reflexes and how to test them.

Reflexes are involuntary muscle contractions in response to a stimulus. They provide valuable information about the integrity of the nervous system. Several reflexes are routinely tested:

- Deep Tendon Reflexes (DTRs): These involve tapping a tendon with a reflex hammer. Examples include the biceps, triceps, brachioradialis, patellar (knee jerk), and Achilles reflexes. The response is graded on a scale (0-4+), indicating the strength of the reflex. Hyporeflexia (diminished reflexes) or hyperreflexia (exaggerated reflexes) can signify neurological issues.

- Superficial Reflexes: These involve stimulating the skin. The abdominal reflex involves stroking the abdomen, causing contraction of the abdominal muscles. The plantar reflex involves stroking the sole of the foot; a normal response is plantarflexion of the toes. An abnormal response (Babinski sign – dorsiflexion of the big toe and fanning of other toes) indicates upper motor neuron lesion.

Example: A patient with a knee jerk reflex graded as 0/4+ suggests a lower motor neuron lesion affecting the pathway. A Babinski sign is a critical finding suggesting upper motor neuron damage, often seen in stroke or spinal cord injury.

Q 11. How do you assess for peripheral neuropathy?

Peripheral neuropathy is damage to nerves outside the brain and spinal cord. Assessment involves a comprehensive neurological examination, focusing on sensory, motor, and autonomic functions:

- Sensory Examination: Assess light touch, pinprick sensation, temperature sensation, vibration sense (using a tuning fork), and proprioception (awareness of joint position). Compare sensations between sides of the body.

- Motor Examination: Assess muscle strength, tone, bulk, and reflexes in the extremities. Look for muscle wasting, fasciculations (involuntary muscle twitching), or weakness.

- Autonomic Examination: Check for signs of autonomic dysfunction, such as changes in heart rate, blood pressure, sweating, or bowel/bladder function.

Special tests might include nerve conduction studies (NCS) and electromyography (EMG) to pinpoint the location and severity of nerve damage.

Example: A patient complaining of numbness and tingling in their feet, along with decreased reflexes in their ankles and reduced vibration sense, suggests peripheral neuropathy. Further investigations like NCS and EMG can help determine the underlying cause.

Q 12. What are the common causes of syncope and how would you investigate?

Syncope, or fainting, is a sudden, temporary loss of consciousness due to reduced blood flow to the brain. Common causes include:

- Vasovagal Syncope: This is the most common type, triggered by emotional stress, pain, dehydration, or prolonged standing. It involves a sudden drop in blood pressure and heart rate.

- Cardiac Syncope: This is caused by heart rhythm problems (arrhythmias) or structural heart disease, leading to insufficient blood flow to the brain. It can be life-threatening.

- Orthostatic Hypotension: This is a drop in blood pressure upon standing, often due to medication side effects or dehydration.

- Neurological Syncope: This can be caused by seizures, stroke, or other neurological conditions.

Investigation involves a detailed history, including the circumstances surrounding the syncopal episode, and a thorough physical examination. Further investigations may include an electrocardiogram (ECG), echocardiogram, tilt-table test, and blood tests to rule out underlying conditions.

Example: A patient experiencing recurrent syncope during emotional stress, with a gradual onset of lightheadedness and slow recovery, points towards vasovagal syncope. However, a patient with sudden, unexplained loss of consciousness and palpitations warrants urgent cardiac evaluation.

Q 13. Explain the process of diagnosing pneumonia.

Diagnosing pneumonia involves a combination of clinical evaluation and investigations. Key features include:

- Symptoms: Cough (often productive), fever, chills, shortness of breath, chest pain, fatigue.

- Physical Examination: Auscultation of the lungs often reveals crackles (rales) or wheezes. The patient may exhibit increased respiratory rate, decreased breath sounds, or dullness to percussion over the affected area.

- Chest X-ray: This is the primary imaging modality, showing characteristic infiltrates or consolidation in the lung fields.

- Blood tests: Complete blood count (CBC) may show an elevated white blood cell count (leukocytosis). Blood cultures can identify the causative organism.

- Sputum analysis: Examining sputum can help identify the type of bacteria or other pathogens responsible for the infection.

Based on the clinical picture, chest X-ray findings, and lab results, a diagnosis of pneumonia can be made, and appropriate treatment (antibiotics, supportive care) can be initiated.

Example: A patient presents with fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Physical examination reveals crackles in the right lower lung field. A chest X-ray shows consolidation in the same area, confirming a diagnosis of pneumonia.

Q 14. How would you differentiate between different types of headaches?

Differentiating between headache types requires careful attention to the characteristics of the headache, including its location, onset, duration, intensity, associated symptoms, and triggers.

- Tension-type headaches: These are the most common type, characterized by mild to moderate pain, usually described as a tight band or pressure around the head. They are often bilateral and not aggravated by physical activity.

- Migraine headaches: These are often severe, throbbing headaches, usually unilateral (affecting one side of the head), and accompanied by nausea, vomiting, photophobia (sensitivity to light), and phonophobia (sensitivity to sound). They can be triggered by various factors like stress, caffeine withdrawal, or hormonal changes.

- Cluster headaches: These are severe, unilateral headaches characterized by excruciating pain around the eye, often accompanied by tearing, nasal congestion, and eyelid swelling. They occur in clusters, with multiple headaches occurring over a period of days or weeks, followed by periods of remission.

- Sinus headaches: These are caused by inflammation or infection of the sinuses and usually associated with facial pain and tenderness.

- Secondary headaches: These are headaches caused by underlying conditions such as meningitis, brain tumors, or subarachnoid hemorrhage. They require immediate medical attention.

A detailed history is essential. Red flags that necessitate further investigation include sudden onset of severe headache, headache with fever or stiff neck, headache accompanied by neurological symptoms (weakness, numbness, vision changes), or a change in the pattern of pre-existing headaches.

Example: A patient with a unilateral, throbbing headache, accompanied by nausea and sensitivity to light, strongly suggests a migraine. A patient with a sudden, severe, thunderclap headache warrants immediate neuroimaging to rule out a life-threatening condition like subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Q 15. What are the key findings in a patient with congestive heart failure?

Congestive heart failure (CHF) occurs when the heart can’t pump enough blood to meet the body’s needs. Physical examination findings vary depending on the severity and underlying cause but often include:

- Cardiovascular findings: Tachycardia (rapid heart rate), tachypnea (rapid breathing), S3 gallop (an extra heart sound indicating poor ventricular filling), S4 gallop (indicating atrial contraction against a stiff ventricle), pulmonary edema (fluid in the lungs, leading to crackles on lung auscultation), jugular venous distension (JVD, swelling of the neck veins indicating increased venous pressure), and diminished peripheral pulses.

- Respiratory findings: Dyspnea (shortness of breath), particularly on exertion or when lying flat (orthopnea), paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (sudden shortness of breath at night), and wheezes (due to bronchospasm from pulmonary congestion).

- Other findings: Edema (swelling) in the lower extremities, ascites (fluid in the abdomen), and hepatomegaly (enlarged liver) due to venous congestion. Patients may also exhibit fatigue, weakness, and reduced exercise tolerance.

For example, a patient presenting with shortness of breath, crackles in the lung bases, an S3 gallop, and leg edema would strongly suggest CHF. The specific findings will guide further investigations such as echocardiography and blood tests (BNP levels) to confirm the diagnosis and determine the severity and cause.

Career Expert Tips:

- Ace those interviews! Prepare effectively by reviewing the Top 50 Most Common Interview Questions on ResumeGemini.

- Navigate your job search with confidence! Explore a wide range of Career Tips on ResumeGemini. Learn about common challenges and recommendations to overcome them.

- Craft the perfect resume! Master the Art of Resume Writing with ResumeGemini’s guide. Showcase your unique qualifications and achievements effectively.

- Don’t miss out on holiday savings! Build your dream resume with ResumeGemini’s ATS optimized templates.

Q 16. Describe your approach to managing a patient with acute chest pain.

Managing a patient with acute chest pain requires a systematic and rapid approach, prioritizing the identification and treatment of life-threatening conditions like acute myocardial infarction (heart attack).

- Immediate assessment: Obtain vital signs (blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation), listen to the heart and lungs, and assess the patient’s level of pain, location, radiation, and associated symptoms (nausea, sweating, shortness of breath).

- ECG: Perform an electrocardiogram immediately to identify ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), a serious form of heart attack requiring immediate intervention.

- Cardiac biomarkers: Order blood tests for cardiac enzymes (troponin, CK-MB) to help diagnose myocardial injury.

- Oxygen therapy: Administer supplemental oxygen if needed to maintain oxygen saturation above 94%.

- Pain management: Administer pain relief medication (e.g., nitroglycerin) if medically appropriate and under the guidance of ECG findings.

- Further investigation: Depending on the initial assessment, additional investigations might include chest X-ray, echocardiography, or cardiac catheterization.

- Treatment: Treatment varies greatly based on the underlying cause. This might include thrombolytic therapy (clot-busting drugs) for STEMI, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for blocked coronary arteries, or other medications depending on the diagnosis.

Consider a scenario where a 65-year-old male presents with crushing chest pain radiating to his left arm and jaw, associated with nausea and sweating. The immediate action would be to take an ECG and obtain cardiac biomarkers. If the ECG shows ST-segment elevation, immediate transfer to a cardiac catheterization lab for PCI is crucial. Delaying treatment in STEMI can lead to significant myocardial damage.

Q 17. Explain the different types of skin rashes and their clinical significance.

Skin rashes are diverse and their clinical significance hinges on their appearance, distribution, and associated symptoms. Several types include:

- Macules: Flat, discolored spots (e.g., freckles, measles).

- Papules: Raised, solid bumps (e.g., acne, warts).

- Vesicles: Small, fluid-filled blisters (e.g., chickenpox, herpes zoster).

- Bullae: Large, fluid-filled blisters (e.g., bullous pemphigoid).

- Pustules: Pus-filled bumps (e.g., acne, impetigo).

- Plaques: Raised, flat-topped lesions (e.g., psoriasis).

- Nodules: Firm, raised lesions extending deeper into the skin (e.g., lipomas).

- Wheals: Raised, itchy, transient lesions (e.g., urticaria (hives)).

Clinical significance: Rashes can indicate various conditions, from simple infections (e.g., viral exanthems) to more serious systemic diseases (e.g., autoimmune disorders). For example, a butterfly rash across the face is characteristic of systemic lupus erythematosus. An itchy, widespread rash could suggest an allergic reaction. The specific type of rash, along with associated symptoms like fever, itching, pain, or systemic involvement, are crucial for appropriate diagnosis and management.

Q 18. How do you interpret an electrocardiogram (ECG)?

Interpreting an electrocardiogram (ECG) involves analyzing the electrical activity of the heart. It’s a complex skill that requires training and experience, but some basic principles include:

- Heart rate: Determine the heart rate by counting the number of QRS complexes in a 6-second strip and multiplying by 10.

- Rhythm: Assess the regularity of the rhythm (e.g., sinus rhythm, atrial fibrillation).

- P waves: Analyze the P waves for shape and presence (absence might indicate atrial fibrillation). P waves should be present before every QRS complex in normal sinus rhythm.

- QRS complexes: Assess the duration and morphology of the QRS complexes (widening might suggest a bundle branch block). Each QRS complex represents ventricular depolarization.

- ST segments and T waves: Evaluate the ST segments for elevation or depression (indicative of myocardial ischemia or infarction). T waves reflect ventricular repolarization.

- Intervals: Measure the PR interval (time between atrial and ventricular activation) and the QT interval (ventricular depolarization and repolarization).

For example, an ECG showing ST-segment elevation in leads II, III, and aVF would suggest an inferior myocardial infarction. An ECG with irregular rhythm and absent P waves would strongly suggest atrial fibrillation. Precise interpretation requires careful consideration of all ECG components in the context of the patient’s clinical presentation.

Q 19. Describe the assessment of joint pain and inflammation.

Assessing joint pain and inflammation involves a detailed history and physical examination.

- History: Inquire about the onset, location, character, duration, severity, and associated symptoms (fever, fatigue, morning stiffness, etc.).

- Physical examination:

- Inspection: Look for swelling, redness, deformity, or asymmetry.

- Palpation: Assess for warmth, tenderness, and crepitus (a grating sound).

- Range of motion: Test active and passive range of motion to determine the extent of limitation.

- Special tests: Perform specific tests depending on the suspected joint problem (e.g., McMurray test for meniscus tears, Lachman test for ACL injuries).

For example, a patient with knee pain, swelling, warmth, and limited range of motion might suggest arthritis. A history of trauma followed by knee pain, instability, and a positive Lachman test would suggest an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury.

Q 20. What are the key components of a musculoskeletal examination?

A comprehensive musculoskeletal examination involves a systematic assessment of the entire musculoskeletal system.

- Inspection: Observe posture, gait, and any visible abnormalities.

- Palpation: Assess muscle tone, tenderness, and any masses.

- Range of motion: Evaluate the range of motion of each joint, noting any limitations or pain.

- Strength testing: Assess the strength of individual muscle groups using manual muscle testing.

- Neurological examination: Assess reflexes, sensation, and motor function to rule out nerve involvement.

- Special tests: Perform specific tests to assess for ligamentous or meniscal injuries, or other specific conditions depending on the patient’s symptoms and history.

For example, assessing shoulder pain might involve inspection for asymmetry, palpation for tenderness over the rotator cuff muscles, evaluation of range of motion, and performing special tests like the Neer and Hawkins-Kennedy tests for rotator cuff impingement.

Q 21. Explain the process of diagnosing and managing hypertension.

Diagnosing and managing hypertension (high blood pressure) involves a multi-step process.

- Screening: Regular blood pressure measurement is crucial. Hypertension is often asymptomatic, so regular checkups are essential.

- Confirmation: Elevated blood pressure should be confirmed on multiple occasions. A single high reading is not sufficient for a diagnosis.

- Risk factor assessment: Identify contributing factors like obesity, smoking, family history, high cholesterol, and diabetes.

- Lifestyle modifications: Encourage lifestyle changes such as weight loss, regular exercise, a healthy diet low in sodium and saturated fats, and smoking cessation.

- Pharmacological treatment: If lifestyle modifications are insufficient to control blood pressure, medication is usually indicated. Choices depend on the patient’s overall health, comorbidities, and other medications they take. Common antihypertensive medications include diuretics, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta-blockers, and calcium channel blockers.

- Monitoring: Regular follow-up appointments are essential to monitor blood pressure, assess treatment effectiveness, and adjust medication as needed.

For instance, a patient with consistently elevated blood pressure might be started on a thiazide diuretic and advised on lifestyle changes. If blood pressure remains uncontrolled, additional medications might be added. Regular monitoring ensures optimal blood pressure control and reduces the risk of complications like stroke, heart attack, and kidney disease.

Q 22. How do you assess for dehydration?

Assessing for dehydration involves a multifaceted approach combining history taking and physical examination findings. It’s not simply about thirst; severe dehydration can be life-threatening and requires immediate attention.

History: Inquire about recent fluid intake, diarrhea, vomiting, fever, excessive sweating (e.g., during strenuous exercise), or polyuria (frequent urination). Recent illnesses or medication use can be significant.

Physical Examination: This is crucial. Look for:

Orthostatic Hypotension: A drop in blood pressure upon standing, indicating decreased blood volume.

Tachycardia: Increased heart rate, the body’s attempt to compensate for low blood volume.

Dry Mucous Membranes: Check the mouth and tongue for dryness. A sticky feeling indicates reduced saliva production.

Sunken Eyes: A classic sign, especially in children. Loss of subcutaneous fat causes a hollow appearance.

Skin Turgor: Gently pinch a fold of skin on the forearm or abdomen. Slow return to its normal position indicates dehydration. In infants, assess skin turgor on the abdomen.

Reduced Urine Output: Decreased urine volume and concentrated urine (dark yellow) indicate dehydration.

Changes in mental status: Confusion, lethargy, or decreased responsiveness in severe cases.

Example: A young athlete presents with dizziness and rapid heart rate after a long, hot practice with inadequate fluid intake. Dry mouth, decreased urine output, and poor skin turgor confirm dehydration.

Q 23. Describe the steps in performing a neurological assessment in a child.

A neurological assessment in a child requires a gentle, age-appropriate approach, adapting techniques based on the child’s developmental stage. It focuses on evaluating mental status, cranial nerves, motor function, reflexes, and sensory function.

Mental Status: Assess alertness, orientation (person, place, time), attention span, and cognitive abilities. Use age-appropriate tasks to evaluate these.

Cranial Nerves: Assess function through observation and simple tests (e.g., checking pupillary response to light, evaluating facial movements, assessing hearing). Adjust techniques according to the child’s age and cooperation.

Motor Function: Observe spontaneous movements, muscle strength (e.g., by having the child push against your hands), and posture. Assess for tremors, rigidity, or weakness.

Reflexes: Test deep tendon reflexes (e.g., patellar reflex, biceps reflex) using a reflex hammer. Note the presence or absence of reflexes and their intensity.

Sensory Function: Assess touch, pain, and temperature sensation in different body parts. Use age-appropriate techniques, engaging the child in interactive games if necessary.

Example: A 5-year-old child after a fall. You assess their alertness and orientation, check their pupil reaction to light, test their muscle strength by having them squeeze your fingers, and assess their reflexes. You’d adapt your approach to use playful techniques and avoid causing unnecessary stress.

Q 24. What are the common causes of shortness of breath and how would you evaluate them?

Shortness of breath (dyspnea) has many causes, ranging from mild to life-threatening. A thorough evaluation is vital to determine the underlying problem.

Common Causes:

Cardiac: Congestive heart failure, heart valve disease, myocardial infarction (heart attack), arrhythmias.

Pulmonary: Asthma, pneumonia, pneumothorax (collapsed lung), pulmonary embolism (blood clot in the lung), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pulmonary fibrosis.

Other: Anemia, anxiety, obesity, metabolic acidosis, pleural effusion (fluid around the lungs).

Evaluation:

History: Detailed history of the onset, duration, character of dyspnea, associated symptoms (e.g., cough, chest pain, fever), and any relevant medical history (e.g., cardiac problems, smoking).

Physical Examination: Assess respiratory rate, rhythm, depth; auscultate (listen to) the lungs for abnormal sounds (wheezes, crackles, rhonchi); observe for cyanosis (bluish discoloration of the skin); palpate the chest for tenderness; assess heart sounds for murmurs or gallops.

Investigations: Depending on the suspected cause, investigations might include chest X-ray, electrocardiogram (ECG), arterial blood gas analysis, pulmonary function tests, echocardiogram.

Example: A patient presents with sudden onset shortness of breath and chest pain. The evaluation will include a detailed history, examination, ECG, and likely chest imaging to rule out a pulmonary embolism or myocardial infarction.

Q 25. Explain the process of diagnosing and managing diabetes mellitus.

Diagnosing and managing diabetes mellitus is a complex process requiring a multi-pronged approach. Diabetes is characterized by hyperglycemia (high blood sugar) due to either insufficient insulin production (Type 1) or insulin resistance (Type 2).

Diagnosis:

Symptoms: Frequent urination, excessive thirst, unexplained weight loss, increased hunger, fatigue.

Laboratory Tests: Fasting plasma glucose (FPG), oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), HbA1c (measures average blood glucose over 2-3 months).

Management:

Lifestyle Modifications: Dietary changes (balanced diet, low glycemic index foods), regular physical activity (at least 150 minutes/week of moderate-intensity exercise), weight management.

Medical Management:

Type 1 Diabetes: Requires insulin therapy (injections or insulin pump).

Type 2 Diabetes: Usually starts with oral hypoglycemic agents. Insulin may be needed later in the disease course.

Regular Monitoring: Regular blood glucose monitoring, HbA1c checks, assessment of kidney and eye function.

Example: A patient with symptoms of increased thirst and urination undergoes an FPG test, which reveals elevated blood glucose levels, confirming a diagnosis of Type 2 diabetes. Management includes lifestyle changes, metformin (oral medication), and regular monitoring.

Q 26. How would you differentiate between different types of rashes in children?

Differentiating between rashes in children requires careful observation and consideration of the child’s overall health. The location, appearance (shape, color, size), and distribution of the rash are important clues. It’s essential to consider the child’s age, medical history, and any associated symptoms.

Examples:

Measles (Rubeola): Koplik’s spots (small white spots inside the mouth), characteristic maculopapular rash spreading from head to toes.

Rubella (German Measles): Mild illness with a pink, maculopapular rash, often starting on the face.

Chickenpox (Varicella): Itchy, fluid-filled blisters in various stages of development, often widespread.

Fifth Disease (Erythema infectiosum): “Slapped cheek” rash on the face followed by a lacy rash on the body.

Diaper Rash: Irritation and redness in the diaper area due to moisture and friction.

Atopic Dermatitis (Eczema): Chronic inflammatory condition with dry, itchy skin, often in flexural areas (e.g., elbows, knees).

Allergic Reactions: Hives (urticaria): raised, itchy welts, often triggered by food or medication.

Important Note: Never attempt to diagnose a rash solely based on visual inspection. A thorough history and physical examination are essential. In many cases, referral to a dermatologist or pediatrician is necessary.

Example: A child with a blotchy rash, fever, and Koplik spots suggests measles. Careful observation and consultation are crucial for definitive diagnosis and appropriate management.

Q 27. What are the key features of a physical examination in a patient with suspected appendicitis?

A physical examination in a patient with suspected appendicitis focuses on identifying signs of peritoneal inflammation (irritation of the abdominal lining). The classic presentation is often described as having right lower quadrant (RLQ) pain.

Inspection: Observe the patient’s general appearance for signs of illness (e.g., pallor, sweating, tachycardia). Note any abdominal distension or guarding.

Auscultation: Listen to bowel sounds; decreased bowel sounds can indicate peritonitis (inflammation of the peritoneum).

Palpation: This is crucial and should be performed gently. Palpate all four quadrants of the abdomen, systematically assessing for tenderness, guarding (voluntary or involuntary muscle contraction), rigidity (resistance to palpation due to muscle spasm), and rebound tenderness (pain elicited upon quick release of pressure).

Specific Examination Findings suggestive of Appendicitis:

McBurney’s Point Tenderness: Tenderness to palpation approximately midway between the umbilicus (belly button) and the anterior superior iliac spine (bony prominence of the hip) on the right side.

Rovsing’s Sign: Palpation of the left lower quadrant causes pain in the right lower quadrant.

Psoas Sign: Pain elicited by passive extension of the right hip (stretching the psoas muscle).

Obturator Sign: Pain elicited by passive internal rotation of the right hip (stretching the obturator internus muscle).

Important Note: Appendicitis can present atypically, especially in children and the elderly. The absence of classic signs does not exclude the diagnosis. A high index of suspicion and prompt imaging (ultrasound, CT scan) are crucial for accurate diagnosis and timely management.

Key Topics to Learn for Physical Examination and Diagnosis Interview

- General Principles of Physical Examination: Understanding the systematic approach, including history taking, observation, palpation, percussion, and auscultation. Practical application involves demonstrating proficiency in performing a complete physical exam on a simulated patient or case study.

- Interpreting Vital Signs: Mastering the assessment and interpretation of heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, temperature, and oxygen saturation. Practical application includes analyzing abnormal vital signs and formulating appropriate next steps.

- Specific Examination Techniques: Developing expertise in examining different body systems (cardiovascular, respiratory, neurological, gastrointestinal, etc.). Practical application requires proficiency in identifying relevant physical findings and correlating them with potential diagnoses.

- Diagnostic Reasoning and Hypothesis Generation: Developing strong problem-solving skills by integrating clinical findings with patient history to formulate differential diagnoses. Practical application involves practicing case studies and analyzing diagnostic uncertainties.

- Common Diagnostic Tests and Procedures: Understanding the indications, contraindications, interpretations, and limitations of relevant diagnostic tests (e.g., ECG, X-ray, blood tests). Practical application includes choosing appropriate tests based on clinical presentations.

- Ethical and Legal Considerations: Understanding patient confidentiality, informed consent, and appropriate documentation practices. Practical application includes demonstrating ethical decision-making in various clinical scenarios.

- Communication Skills: Effectively communicating findings to patients and healthcare professionals. Practical application includes practicing clear and concise explanation of diagnoses and treatment plans.

Next Steps

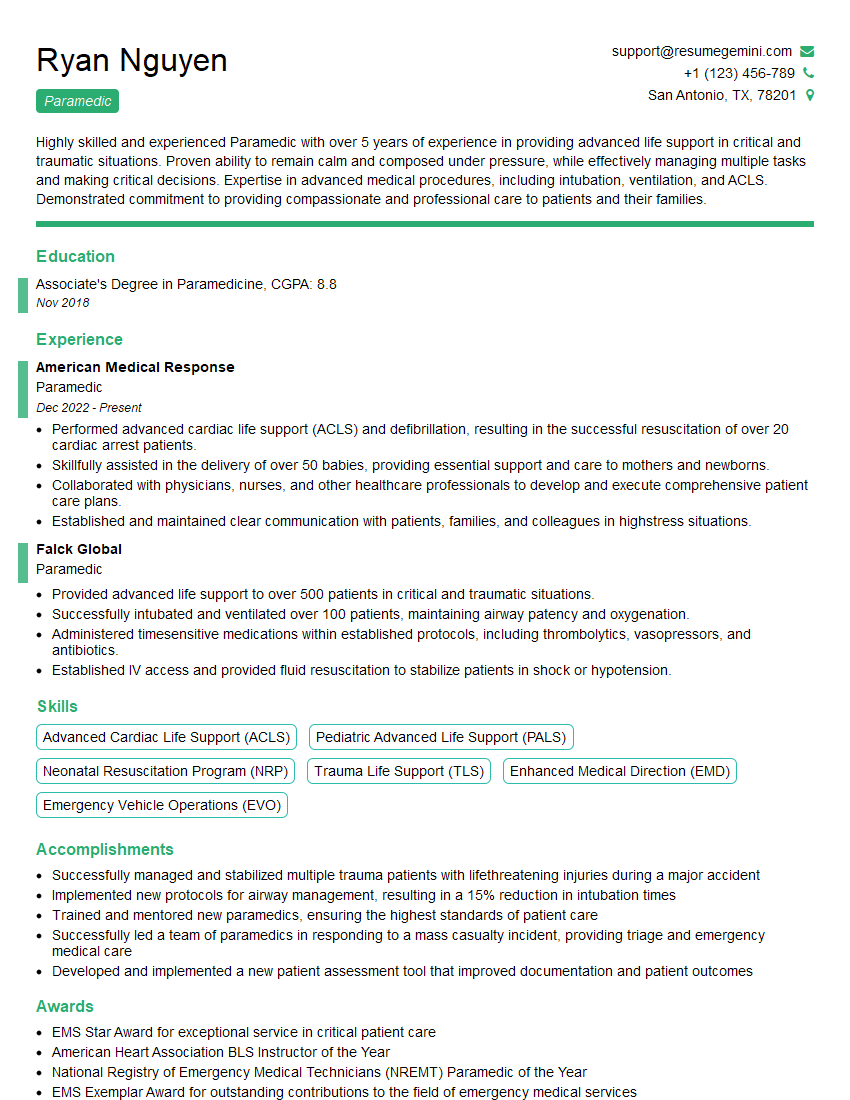

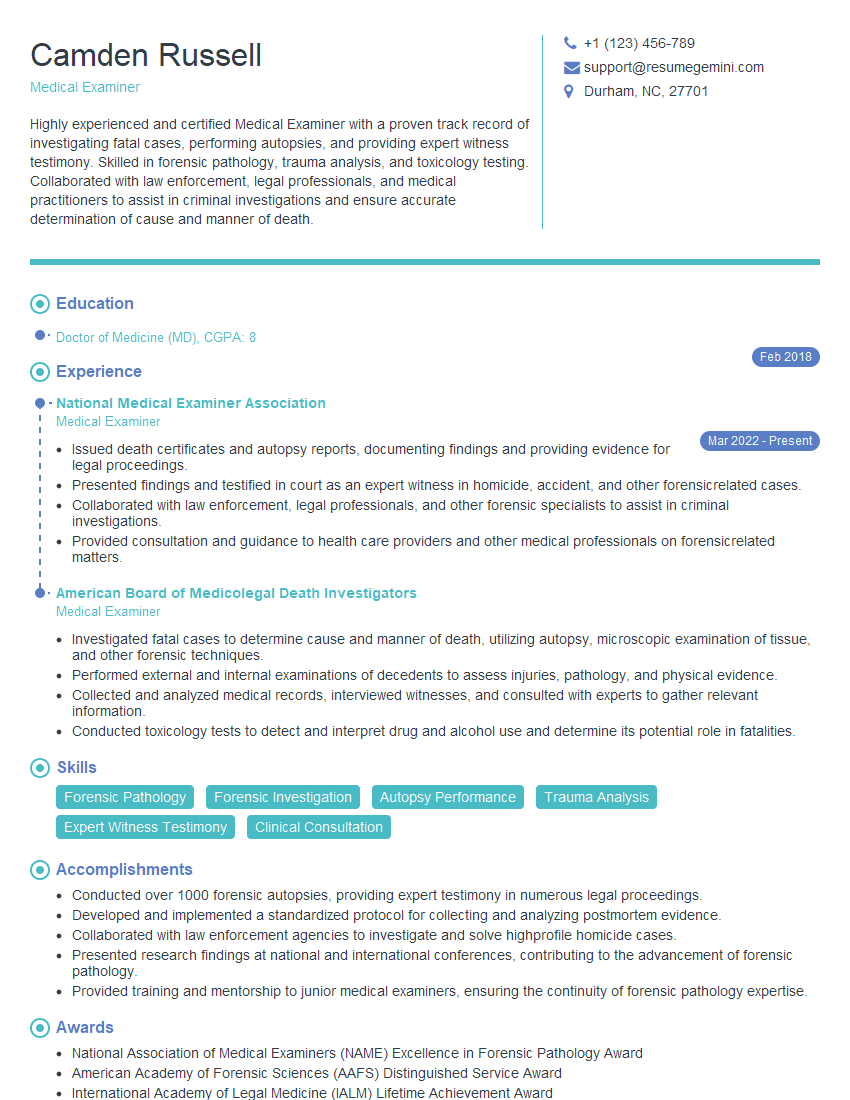

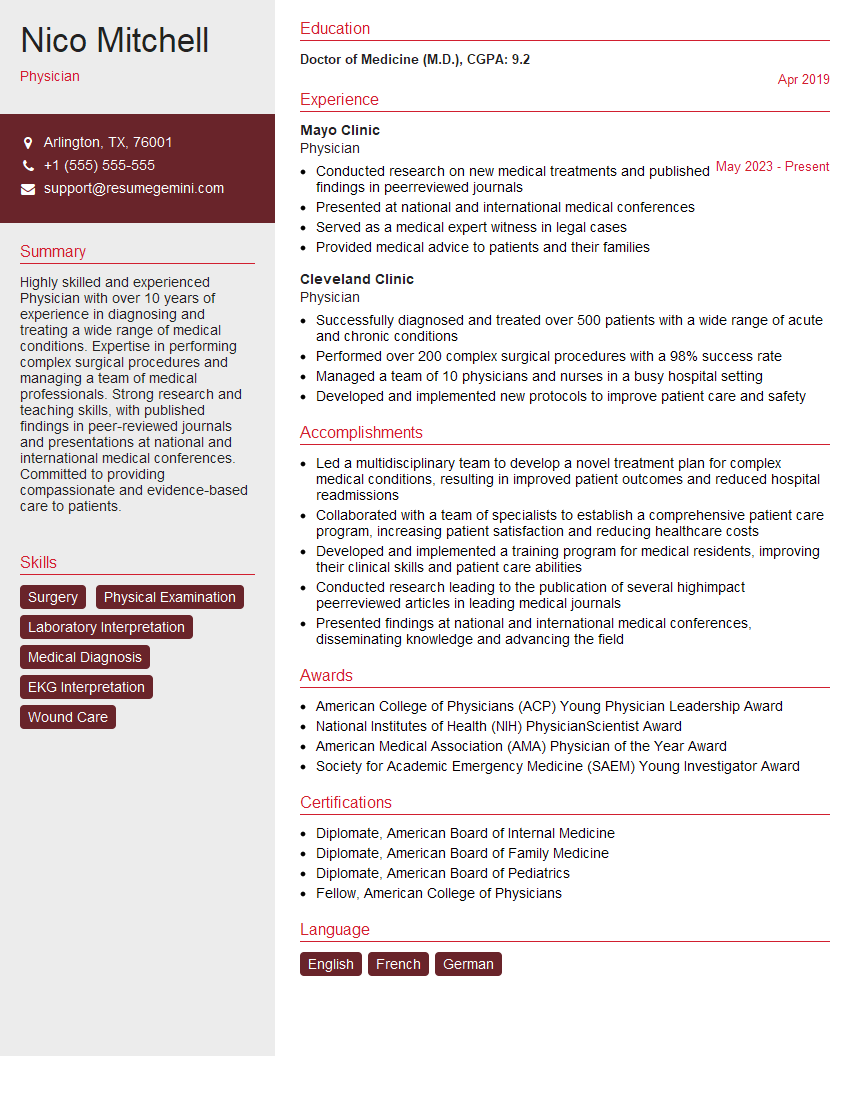

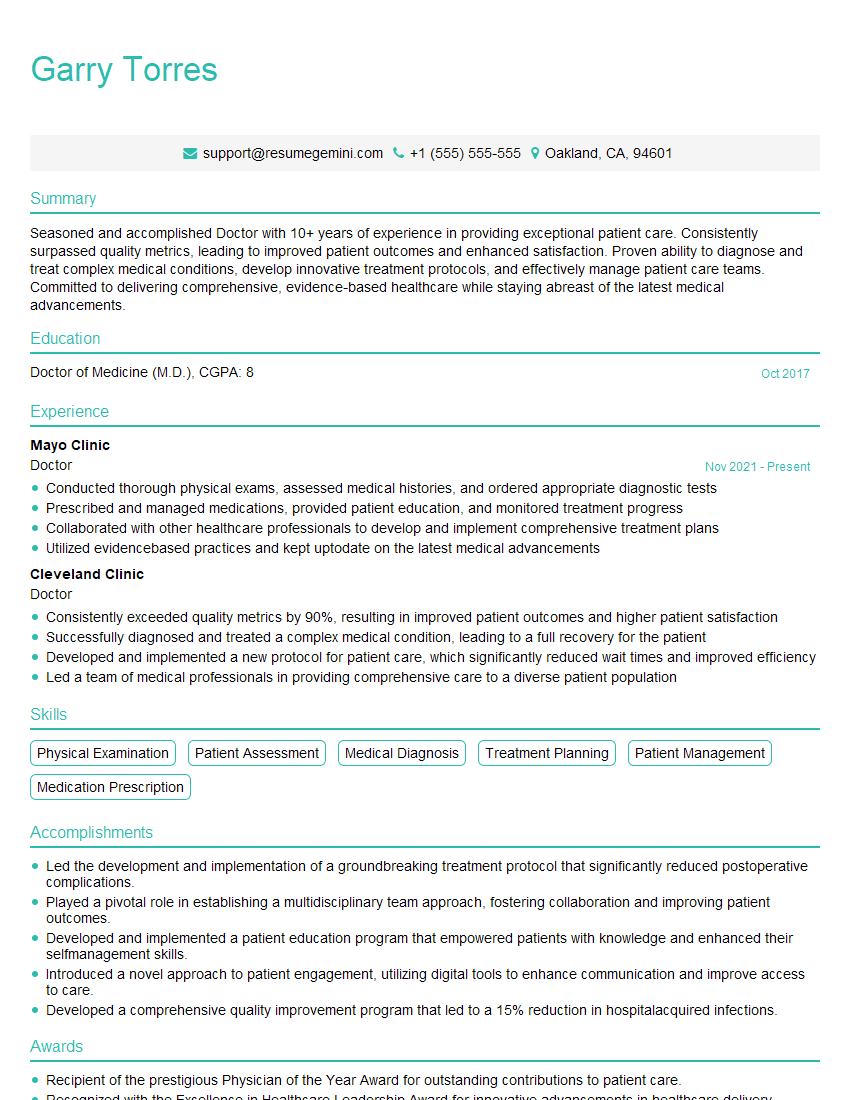

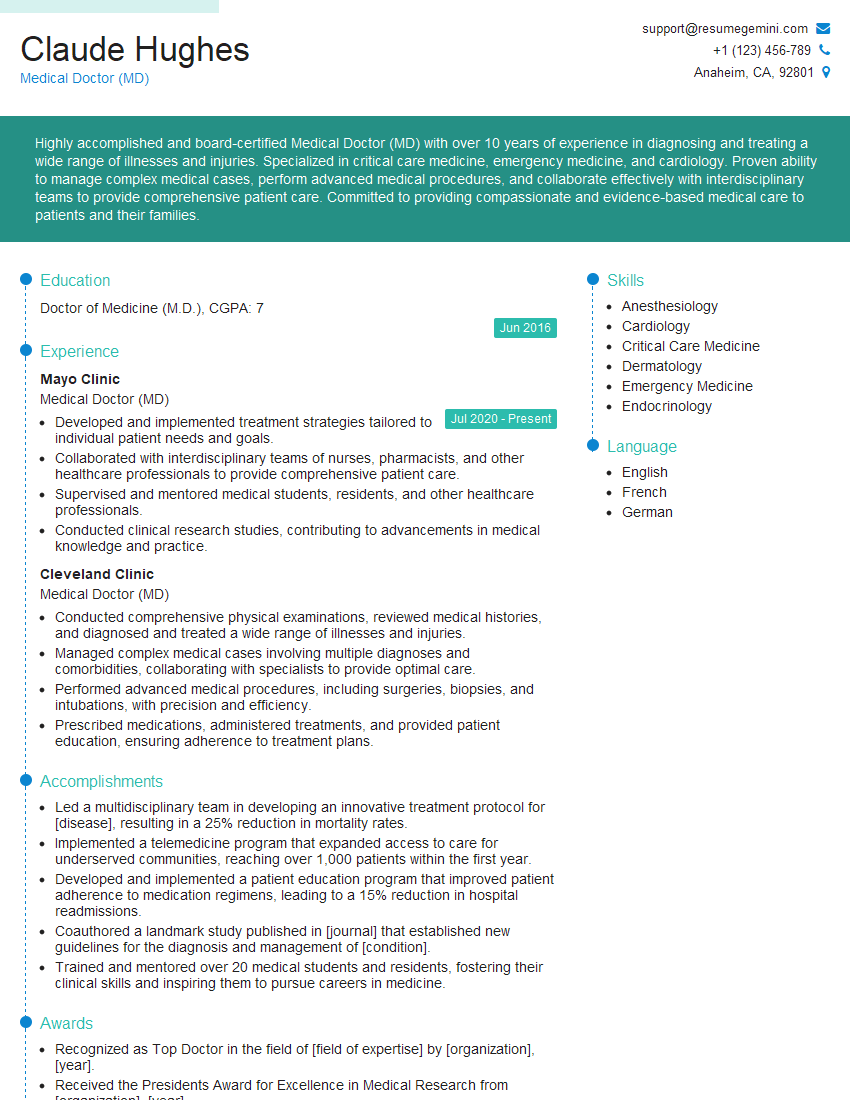

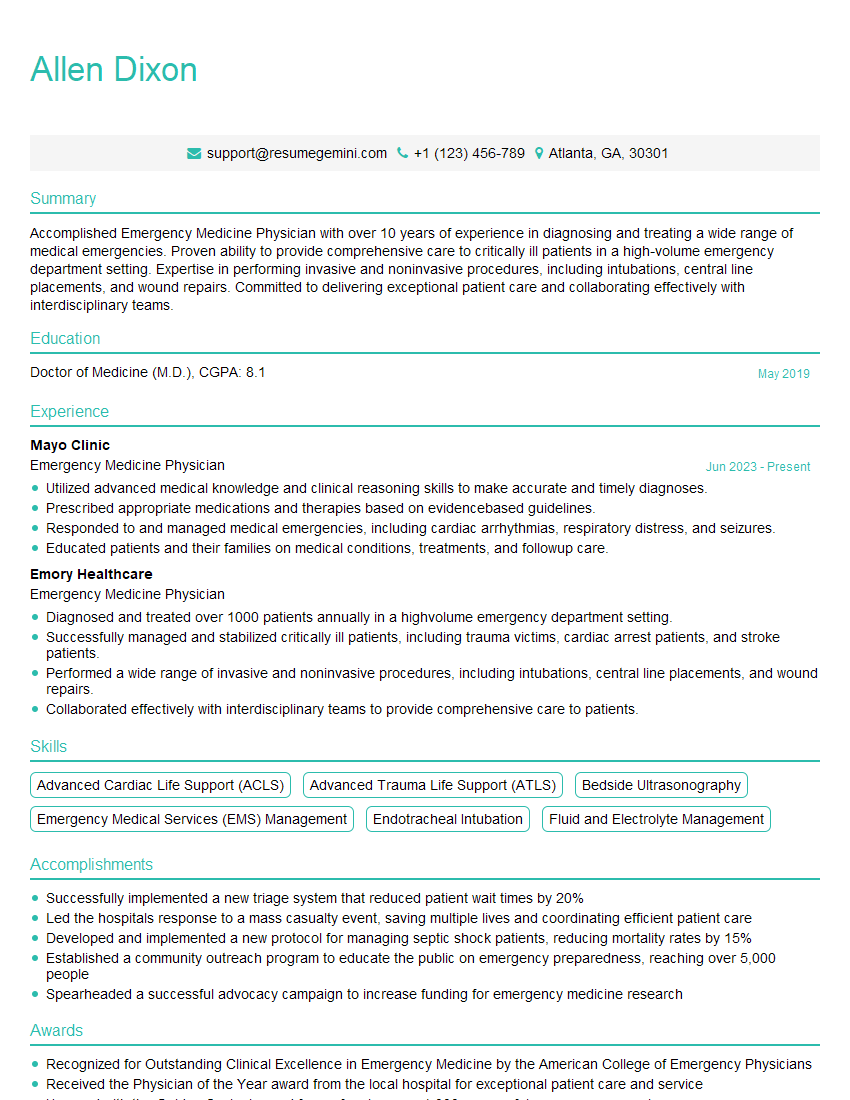

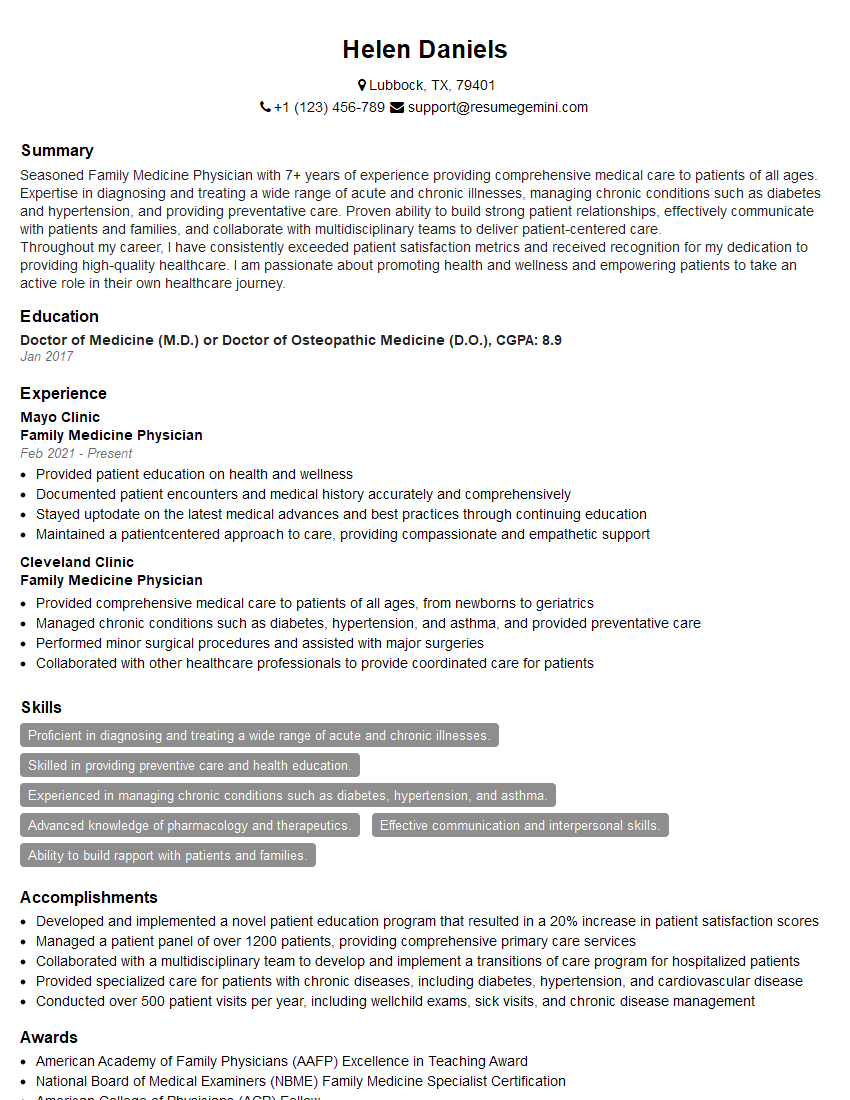

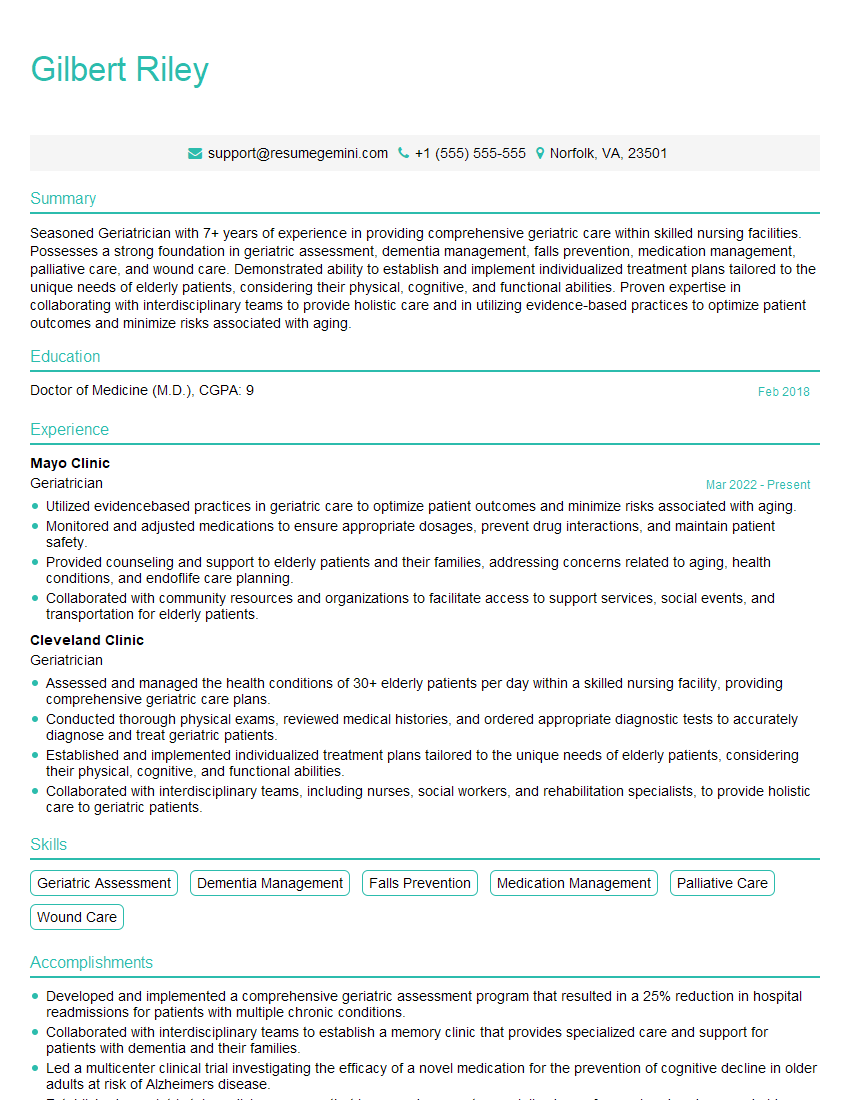

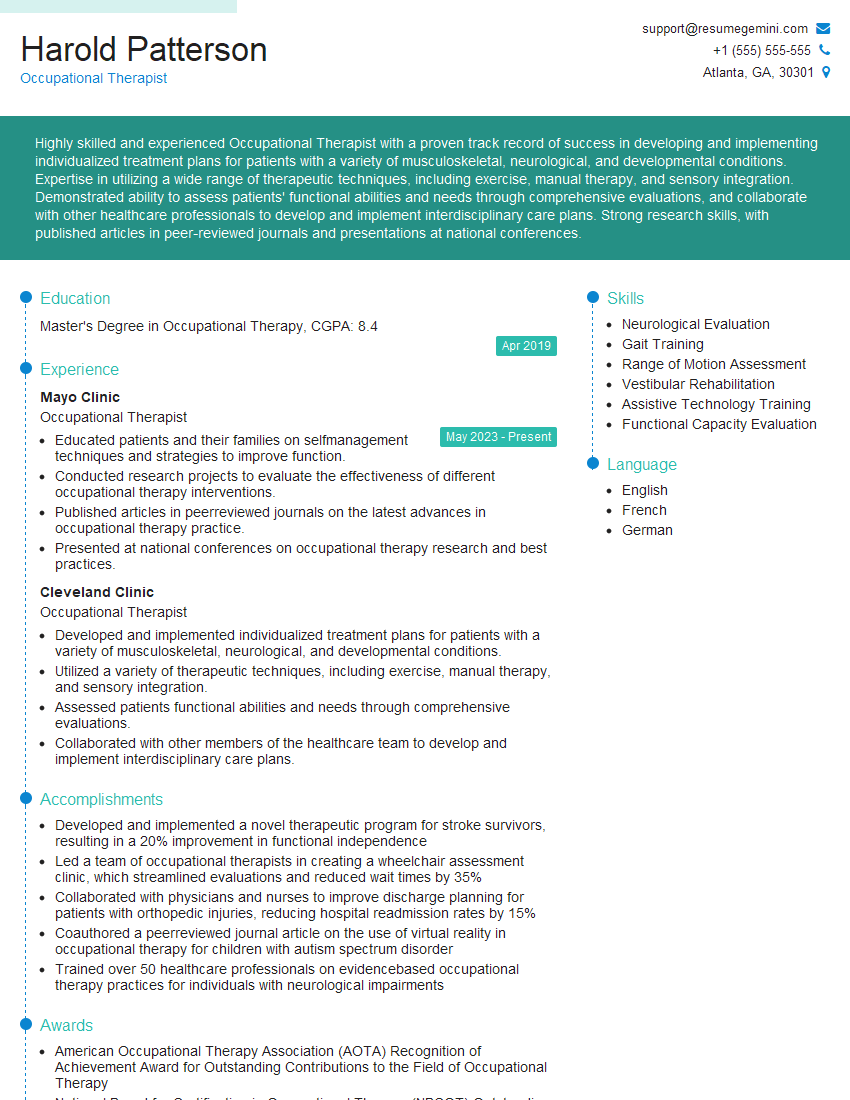

Mastering Physical Examination and Diagnosis is crucial for career advancement in healthcare. A strong foundation in these skills opens doors to diverse and rewarding roles. To maximize your job prospects, create an ATS-friendly resume that highlights your expertise. ResumeGemini is a trusted resource that can help you build a professional and effective resume tailored to your skills and experience. Examples of resumes tailored specifically to Physical Examination and Diagnosis are available to guide you through the process. Invest in crafting a compelling resume; it’s your first impression on potential employers.

Explore more articles

Users Rating of Our Blogs

Share Your Experience

We value your feedback! Please rate our content and share your thoughts (optional).

What Readers Say About Our Blog

This was kind of a unique content I found around the specialized skills. Very helpful questions and good detailed answers.

Very Helpful blog, thank you Interviewgemini team.